CSotD: Deja vu, if that’s what we decide

Skip to comments

Despair was on the national menu in October, 1973. Paul Conrad described the state of the presidency in the words White House Counsel John Ehrlichman had used when, as Watergate investigations began, he said that, rather than confirming Patrick Gray as head of the FBI, they should leave him “slowly, slowly twisting in the wind.”

By October, Ehrlichman, along with Chief of Staff Bob Haldeman, had been fired from the slowly twisting White House. Both would later serve prison terms for their illegal activities while on the president’s staff.

Vice President Spiro Agnew was, as Jeff MacNelly put it, caught with his hand in the cookie jar, having taken kickbacks from corrupt contractors while an official in Baltimore, payments that continued into his time as VP. Although he initially declared that a sitting vice-president could not be indicted, he agreed to step down on October 10.

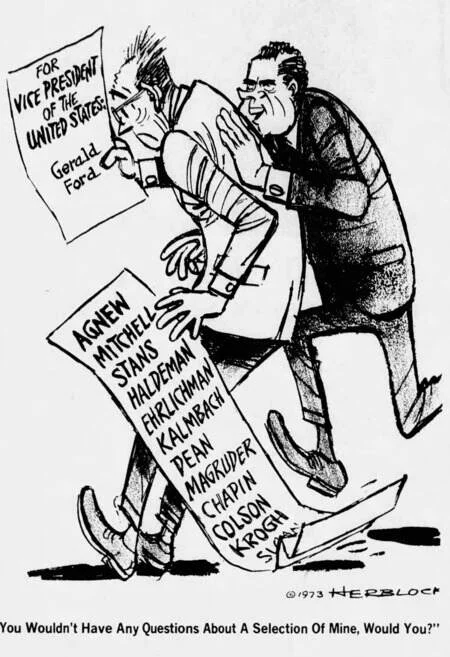

Nixon proposed replacing him with House Minority Leader Gerald Ford, though Herblock had doubts about the president’s judgment when it came to hiring, given the growing corruption roster that was emerging in the Senate Select Committee hearings on Watergate, not simply for the break-in at Democratic headquarters but the burglary of the office of Pentagon Paper leaker Daniel Ellsburg’s psychiatrist, interference in the 1972 elections and various cases of related bribery and cover-ups.

MacNelly saw the appointment of Ford, generally considered a moderate, as an attempt by Nixon to rebuild his image.

But Corky Trinidad didn’t think Nixon — who had elevated Agnew as his attack dog, with the help of speechwriter Patrick Buchanan — really intended to give Ford any such visibility in the administration.

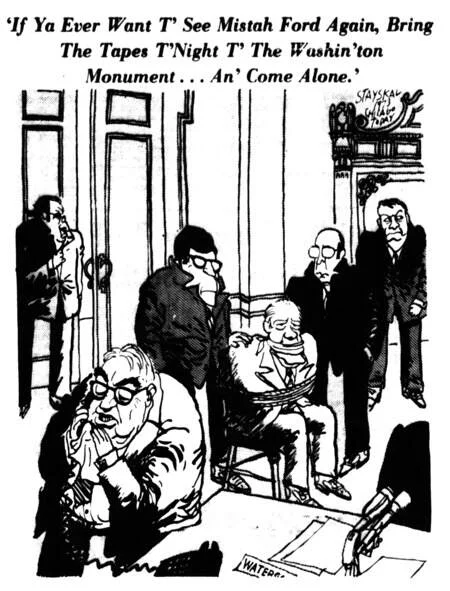

However, there remained the issue of the White House tapes, which were said to reveal Nixon’s conversations with his staff about the Watergate burglary, its cover-up and sundry other corrupt actions. As Wayne Stayskal noted, The Senate threatened to delay confirming Ford unless Nixon gave up his stance about executive privilege and released the tapes.

Stayskal had Senate Select Committee chair Sam Ervin making the muffled phone call, but it should be remembered that the Select Committee on Presidential Campaign Activities included Republicans who participated in, rather than boycotting or attempting to obstruct, the hearings.

Stayskal was not the only voice raised in support of Nixon, and L.D. Warren made the claim that the Democrats had plenty of corruption of their own that they covered up while accusing the president.

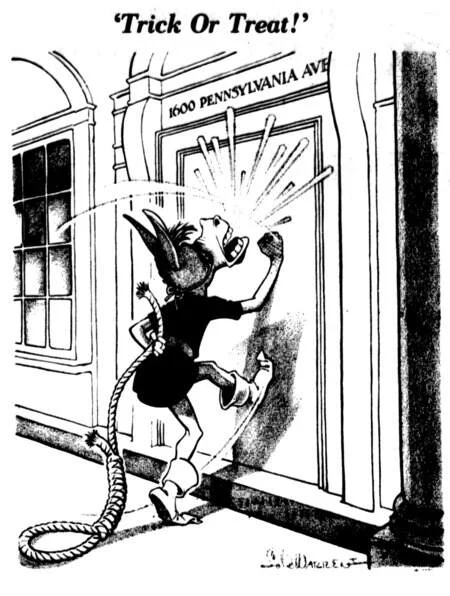

Warren also took advantage of the Halloween season to accuse Democrats of leading a lynch mob against the president, though by the time this cartoon appeared, the Saturday Night Massacre had happened and support for the president was seriously fading.

Nixon had ordered Attorney General Eliot Richardson to fire Archibald Cox, the special investigator looking into the Watergate charges, but Richardson refused and resigned, whereupon Nixon ordered acting FBI Director William Ruckelhaus to do the deed and received another refusal and resignation.

Next in line was Solicitor General Robert Bork, shown here by Gene Bassett as a much smaller man than his predecessors, though it seems doubtful he questioned the coach, because he took the assignment and fired Cox, leading to graffiti and pins saying “Impeach the Coxshucker.”

The dean of Yale Law School, where Bork had taught before joining the government, said he should have joined Richardson and Ruckelshaus in resigning on principle, but conservatives rallied around Bork, who was later nominated to the Supreme Court by Ronald Reagan, though he failed to be confirmed.

According to Dennis Renault, the Massacre left the Watergate investigation shattered and Nixon in place as self-crowned king, replacing Justice as the nation’s governing principle. But he quoted Cox in order to show his own doubts, or hopes.

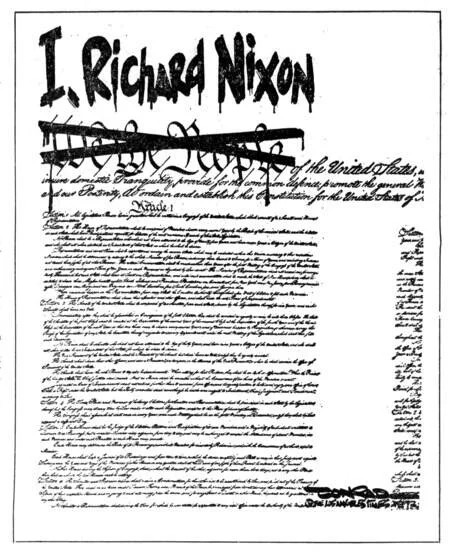

Conrad wasn’t peddling subtlety, and came out with a plain accusation that Nixon was placing himself above the Constitution.

Nor was Herblock willing to pussyfoot around the situation.

There had been a flurry of reported UFO sightings at the time, and several “Take Me To Your Leader” political cartoons, but Conrad took a less frivolous viewpoint in suggesting that the real mystery was in money that was flowing between Nixon supporters and that he suspected might make a landing in one of Nixon’s personal residences.

Nor was Herblock taking his eye off the fact that Nixon appeared to be personally profiting from his position as president. (Perhaps it should be explained that, in 1973, a president was not expected to use his position and power in order to increase his personal wealth, even if by only six figures.)

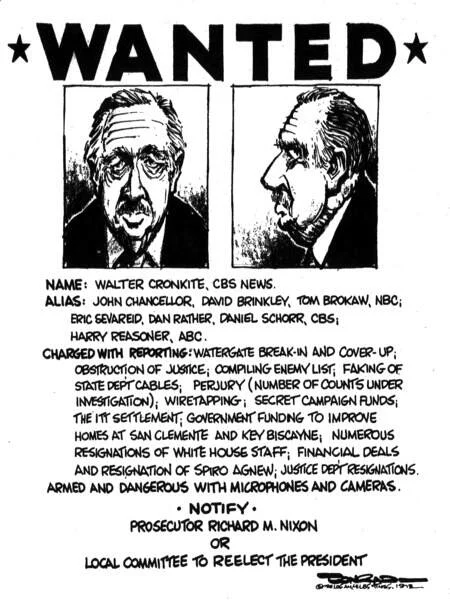

Nixon launched an attack upon the media, and Conrad mocked that as well, listing the offending journalists who had the temerity to report the news. Again, context should be noted: There was no Internet, nor was there a fourth major network promoting favorable partisan alternatives to straight coverage.

As Bill Mauldin pointed out, if the president didn’t like the way he looked in the media, it was largely his own fault for looking like that.

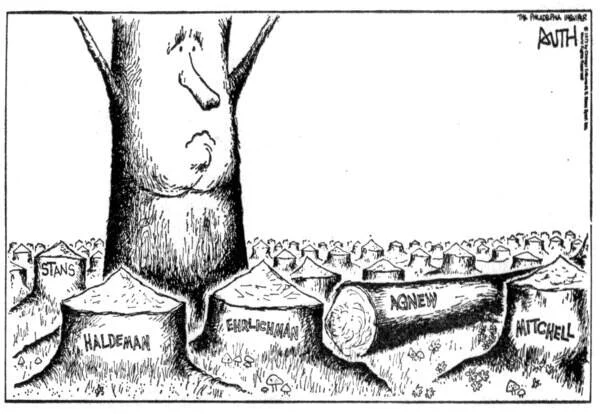

As the resignations, firings and investigations continued, Tony Auth suggested that the remaining tree in this forest must certainly be feeling somewhat nervous.

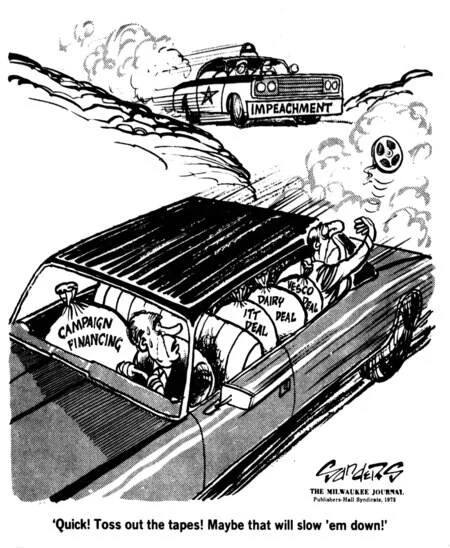

The release of tapes, in the eyes of Bill Sanders, became a bargaining tool for Nixon, who had plenty of other issues that the Committee was likely to probe.

Herblock suggested the futility of Nixon’s desperate coverups, particularly when Nixon claimed that some of the tapes had somehow gone missing, this being before it was discovered that Rosemary Woods had “accidentally” erased 18-and-a-half minutes of a crucial tape.

Herblock contended that disappearing tapes and disappearing staff would not keep the impeachment hearings from disappearing the president.

There were distractions available, and Pat Oliphant mocked Nixon for attempting to highlight the Mideast War not as a confrontation between Israel and its neighbors but as his victory in dealings between the US and the Soviet Union. There had been a settlement and the Soviets had backed off a plan to send their own troops as peacekeepers, but Watergate hadn’t gone away.

And Mauldin expressed outrage over the joint awarding of the Nobel Peace Prize to Henry Kissinger and North Vietnam’s Le Duc Tho, though Tho declined the award.

Mauldin mocked Kissinger some more, suggesting that perhaps he had some personal goals in mind for his planned trip to Beijing.

Don Hesse decried the plea bargains that emerged. Hesse seemed to go back and forth on the scandal but was generally critical of the investigation, and so the matter of hastening things plus obtaining cooperative testimony apparently did not, in his mind, outweigh the further details that might have emerged in a series of trials.

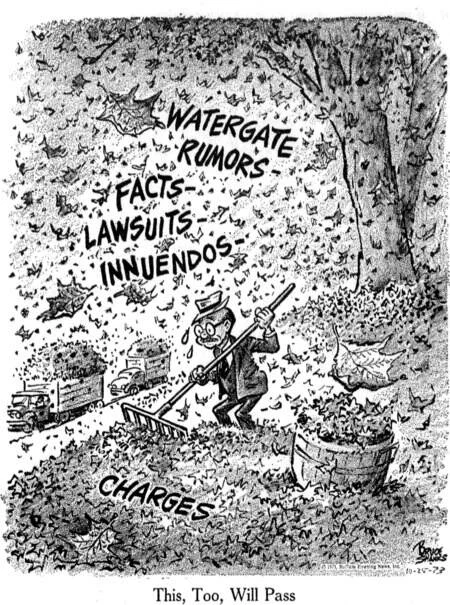

But much as Bruce Shanks may have dismissed it all as a temporary dust-up that would prove as quickly passing as October’s leaves, it wasn’t and it didn’t.

It could have. But the outrage among the public may have persuaded Republicans that loyalty to the nation was more important than their loyalty to their political party. Their unity disappeared as the facts of the case emerged, though seven months passed between the Saturday Night Massacre and Richard Nixon’s resignation.

Archibald Cox had said “Whether ours shall be a government of laws and not of men is now for Congress and ultimately the American people to decide.”

They both decided in favor of a government of laws, and, in so doing, inspired one of the most dynamic speeches in American history:

The ball is now in our court.

Comments 20

Comments are closed.