(Re)Draw Pardner – book review

Skip to commentsRedrawing the Western: A History of American Comics and the Mythic West by William Grady (2024)

Nearly 50 years after Maurice Horn’s Comics of the American West we get another book charting “the Western genre in American comics from the late 1800s through the 1970s and beyond.”

By the time comic strips came along the Real West was already becoming more mythology than reality. The exaggerated stories told in the dime novels of the 1880s and 1890s began to shape the direction of wild and wooly Western tales. And the emerging turn of the century film industry would cement the framing of the cowboy hero from a West that had ended 20 years earlier.

Grady begins with comic strips that would not be considered classic Western. Little Jimmy by James Swinnerton and Krazy Kat by George Herriman were placed in the environs of the American Southwest.; and Frank King’s Gasoline Alley would travel west on vacations. Until the time that Ron Goulart called The Adventurous Decade that would be the Western of comic strips – occasional placement of characters out west or a rare comic featuring the traditions of Native Americans.

In the late 1920s adventure continuity arrives in newspaper comic strips and with that comes the Western of Cowboys and Indians, of the good guys versus the bad guys, of vigilante heroes that “stood for law and order, peace and quiet, God and country, Mom and apple pie.” You know – the Western as we have all come to think of when we hear of the Western brand. The Western in the form of White Boy, Little Joe, Red Ryder, The Lone Ranger, and many others become a constant presence on newspaper comics pages in the 1930s and into the 1970s.

The Western was not ignored when the nascent comic book industry began in the mid-1930s. Then the Western posse of comic books exploded after World War Two. During the Cold War there was no more an American hero than the cowboy.

The turbulent 1960s brought changes to the comic book Western (moreso than the comic strip Western). Mellow characters (Bat Lash), Black cowboys (Lobo), American Indian heroes (Red Wolf), and, following the lead of Clint Eastwood and the Spagetti Westerns, the anti-hero (Jonah Hex).

And then, in 1974 to be exact, the Western is gone.

To be sure the Western didn’t completely disappear, but its ubiquity was sorely subdued. The Western from the mid-1970s to the present day is covered in one, the final, chapter. Like the opening chapter the Westerns there are mostly just a matter of placement, nothing like the classic Western.

William Grady’s intentions for this book is to showcase the comic strip and comic book Westerns as they related to the customs and the conventions of the times they appeared, and how other media, mostly films, influenced the plots and stereotypes of the comics. Grady does a very good job detailing the trajectory of the comic Western genre. My major complaint is that at times he gets too far into the weeds of Hollywood’s impact on the direction of the comics.

It is published by the University of Texas but unlike some books from higher education sources Grady does not go overboard with acadamese. The book remains readable and entertaining and educational.

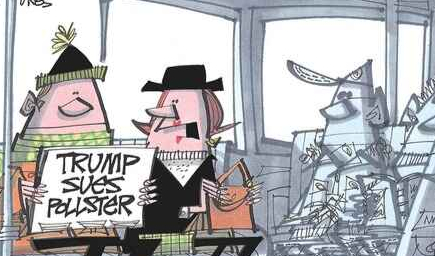

My use of images and characters not used in the book should not be taken as criticism. Horn’s Comics of the American West is the encyclopedic volume of Western comics, Grady’s Redrawing The Western is an admirable companion Western comics history, annotating the directions Western comics took over the course of their existence and what social and political mores determined the dusty trails taken.

Recommended, especially for us Western fans.

Comments

Comments are closed.