CSotD: AAEC/ACC 24, Day One

Skip to comments

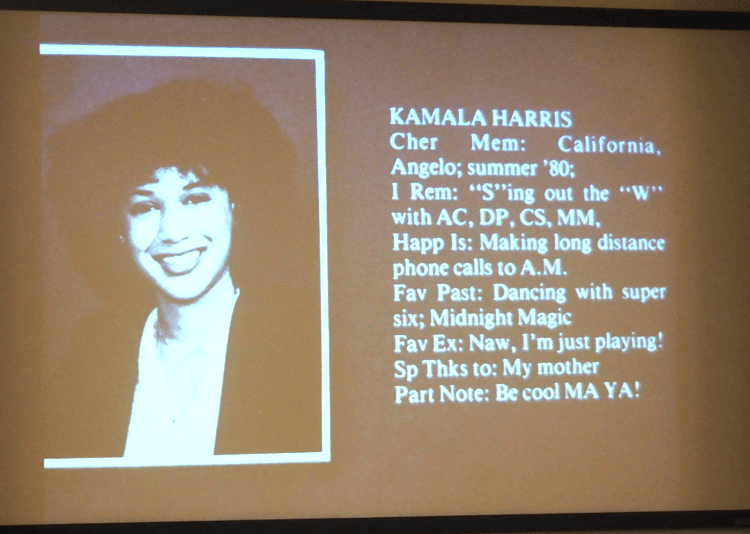

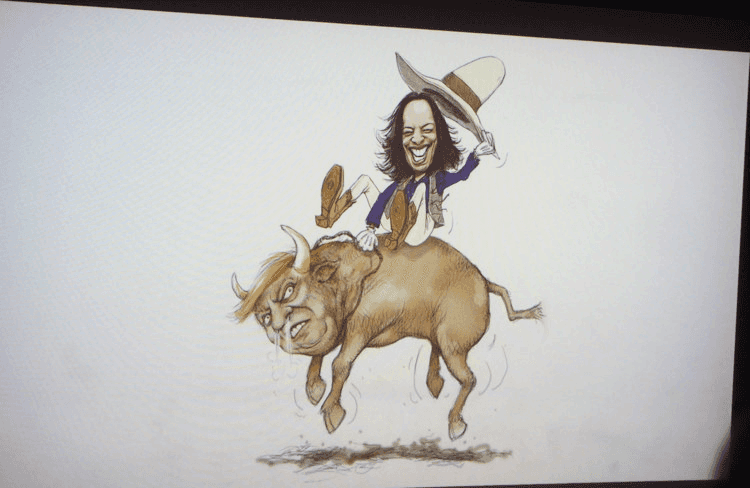

Welcome to Montreal, home of Westmount High, alma mater of Kamala Harris, who, as Terry Mosher (Aislin) reminded us, lived here for a few years when her mother was a professor at McGill.

There will be a lot of graphics today, so the prose will be sparse, and note that a lot was shot at an angle in the dark and processed in my hotel room.

You should pretend I did it all on purpose to give you a sense of being there.

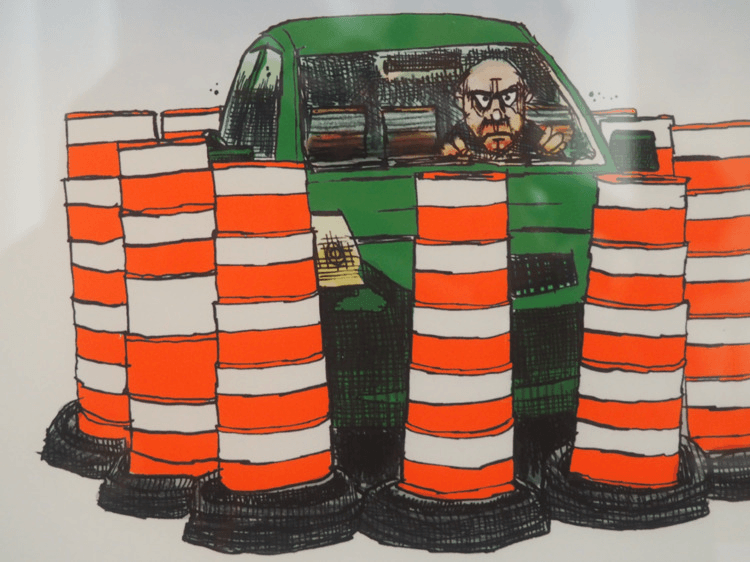

Mosher led off with a number of local cartoons, including a salute to Montreal’s traffic, which chiefly consists of trying to weave through construction.

But he also noted that his paper, the Gazette, has always had two political cartoonists on staff and at one point in his time there had seven.

Add however many exclamation points to that as you wish, but there may have been more Canadian than American cartoonists present, not because the convention is in their country but simply because they’re so much more numerous per newspaper.

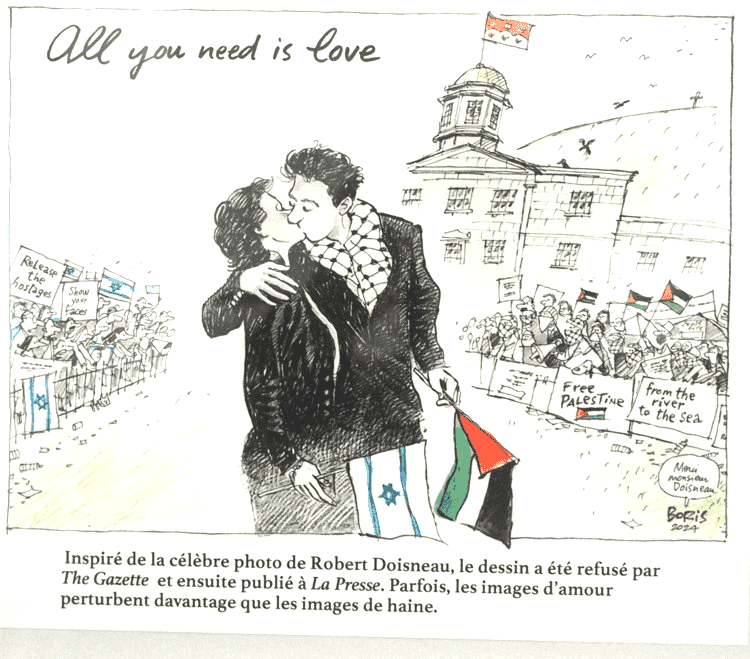

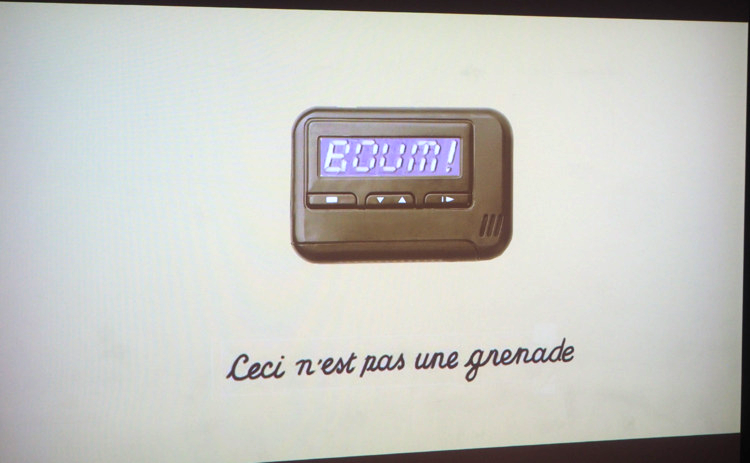

Mosher’s partner in the welcoming was his cohort at the Gazette, Jacques Goldstyn (Boris), who showed us some of his work, including this piece which was rejected by the Gazette, but which he then took across town to La Presse, where it ran despite its English-language heading.

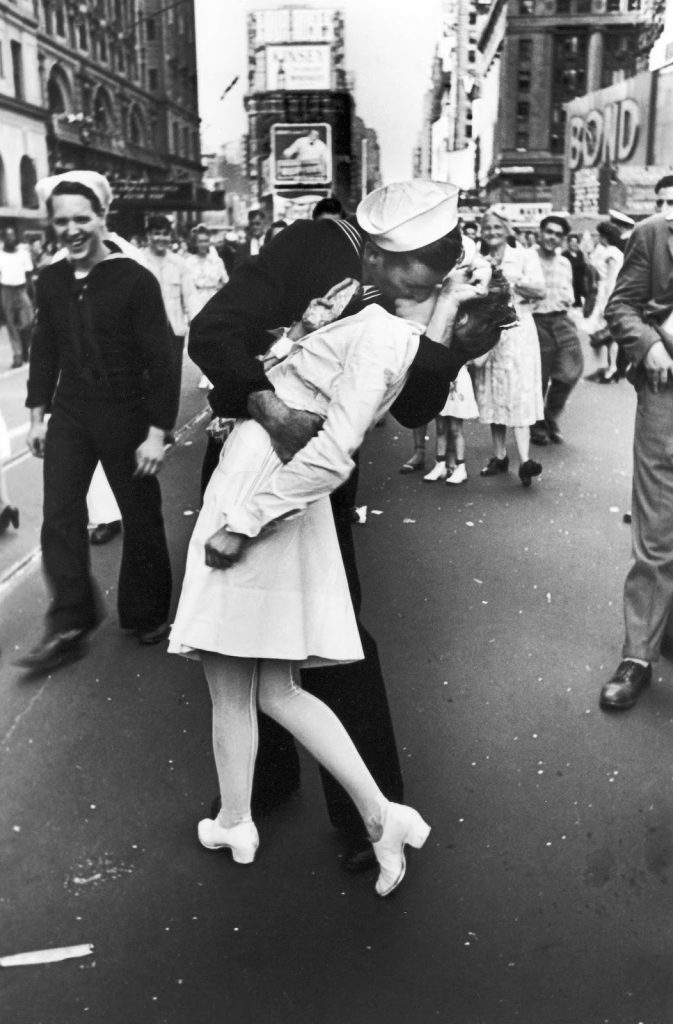

Perhaps francophone editors recognized the riff on Robert Doisneau’s Le baiser de l’Hôtel de Ville, Paris 1950. Or perhaps they were less cautious about offending those with strong feelings about Gaza.

As he explained, drawing bombs and so forth is okay, but you can’t draw two people kissing. His editors explained “We don’t want any trouble.”

There was a lot of that sort of thing in the air throughout the day.

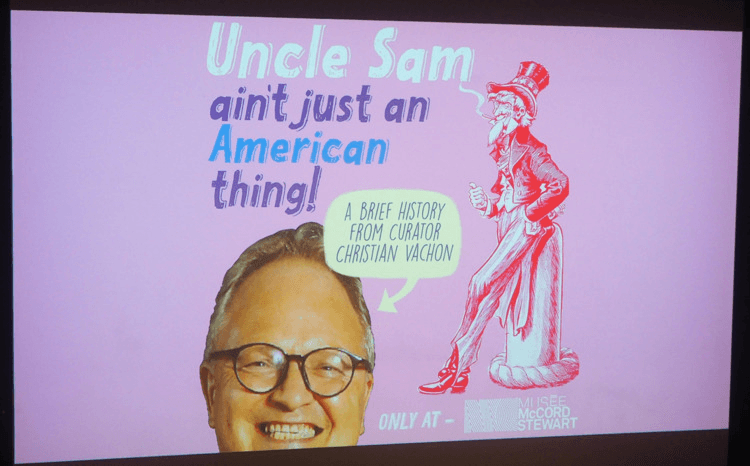

But first, we got a history lesson from Christian Vachon, curator of Musee McCord Stewart which has an astonishing collection of cartoons going back to Canada’s earliest days.

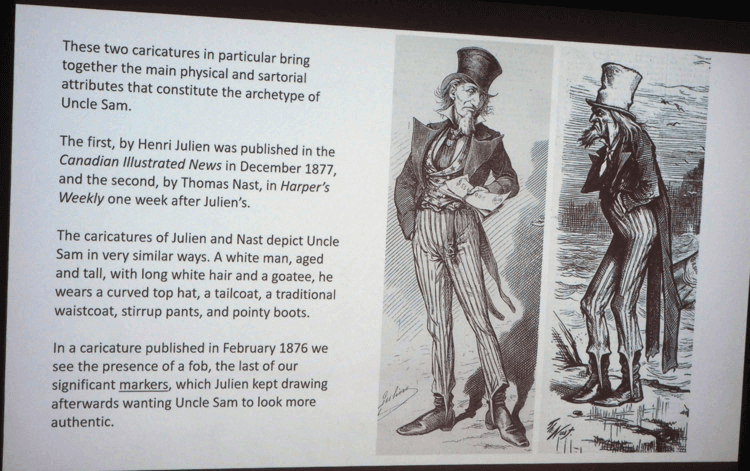

Vachon proposed, and then defended, the theory that cartoon images of Uncle Sam first appeared in Canada before they were picked up by Thomas Nast in New York. The first depiction of Uncle Sam in the Atwater’s collection is 1849, when Nast was nine years old.

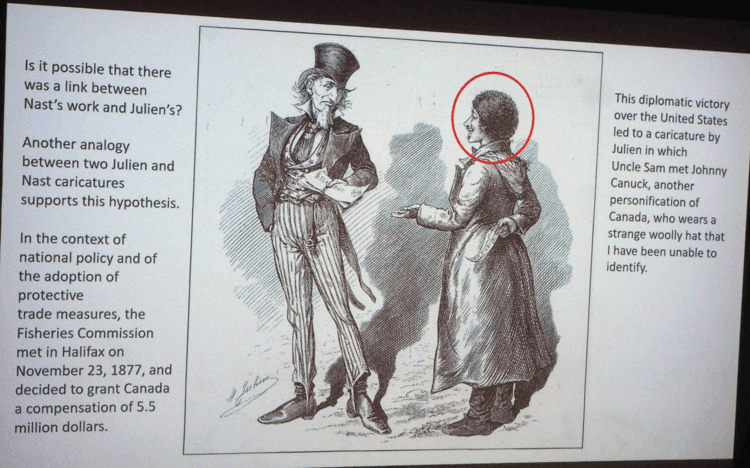

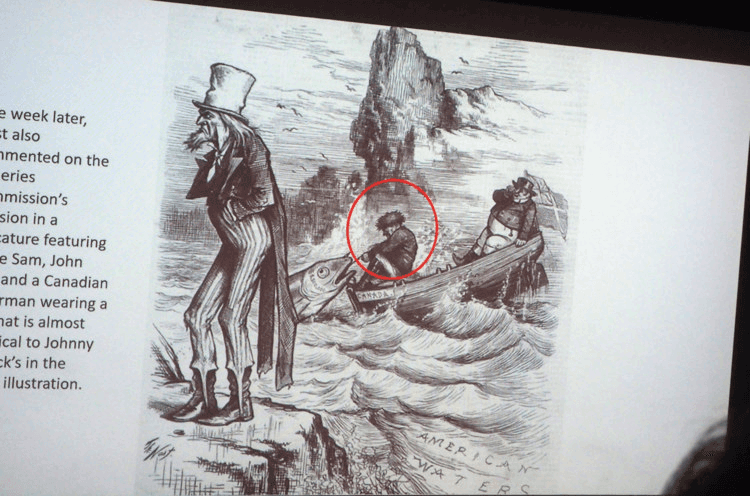

He backed this theory up with a Canadian depiction of Johnny Canuck wearing an odd hat, which then appeared on his head in an American cartoon the next week, proving that the original Canadian publication was readily available in New York City.

As he noted, such national images tend to grow somewhat spontaneously, but in this case much of the seeds appear to have been planted north of the border.

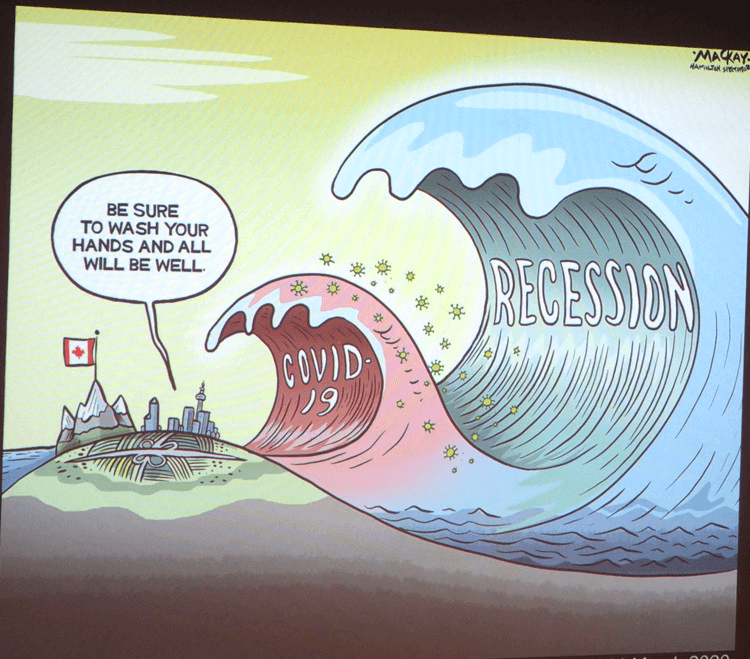

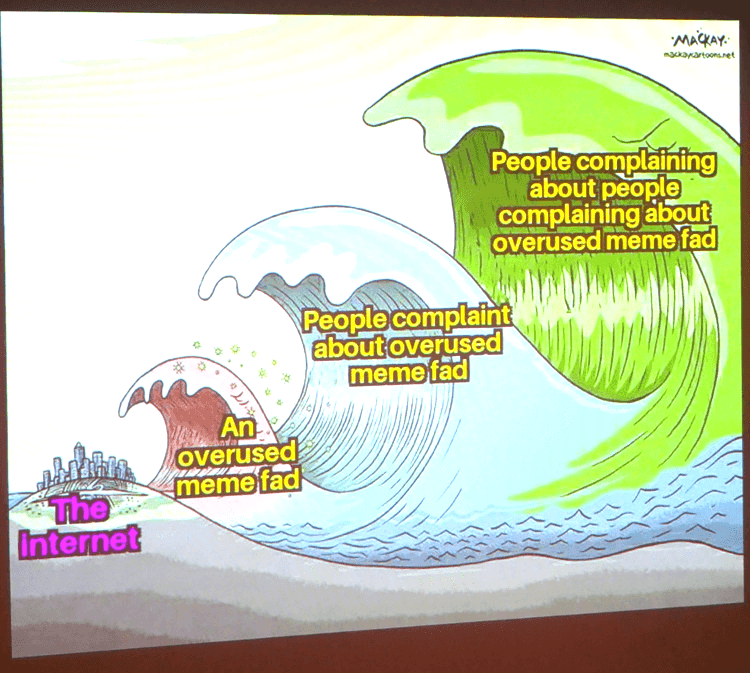

And speaking of how cartoons can morph over time, our next presenter was Graeme MacKay, whose somewhat bitter, very hilarious tale of how his covid cartoon was pirated, pillaged, exploited and otherwise turned inside out and backwards and upside down was so amusing that, with his permission, I’m saving it for another day when it can run entire.

You’ll have to keep coming back so you don’t miss it.

Serge Chapleau of La Presse demonstrated one aspect of working for daily papers, with this pair of cartoons he had poised for editors to run after the Harris/Trump debate.

Obviously, it was the top one they chose.

In addition to his newspaper work, Chapleau also had an animated TV show for several years that was very popular in Quebec and he is a major fixture in French Canada.

His cartoon of Trump and Musk drew gales of laughter, but he added that a young reader didn’t understand why they were smoking. Times change, I suppose.

While for all the pager cartoons I saw just a few weeks ago, I wish I’d seen Chapleau’s take.

Incidentally, he was the first of several cartoonists yesterday who commented that it was easier and more productive to engage with outraged readers in the days when they wrote letters so that there was time for everyone at both ends to ponder before responding.

Today’s instant messaging keeps emotions high and responses hotter than they need to be.

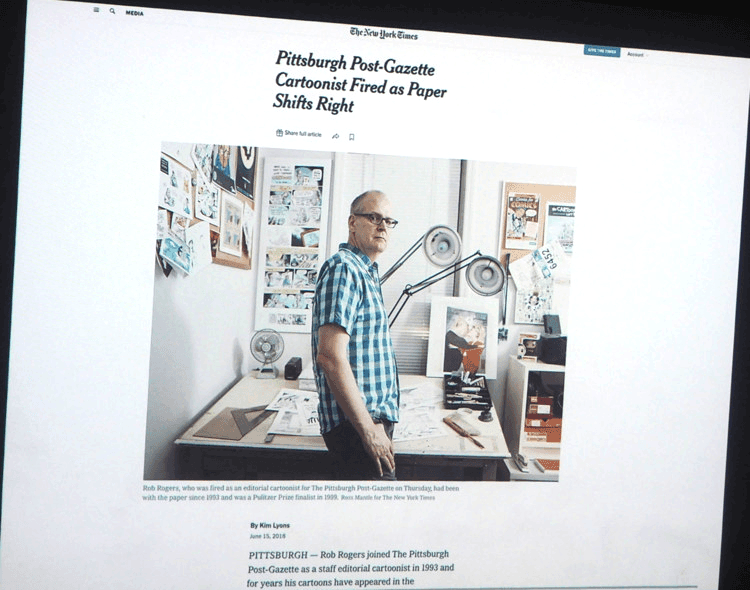

Which observation is a good segue to Rob Rogers and Dwayne Booth (Mr Fish).

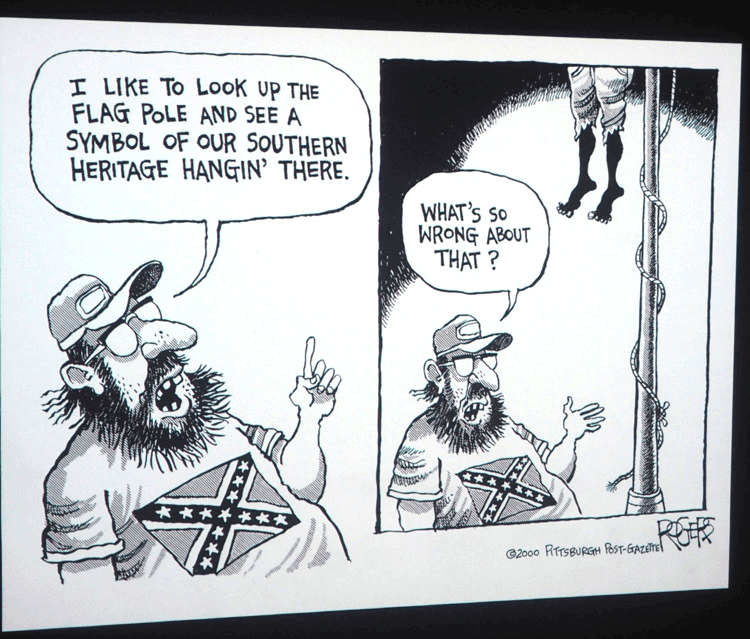

Rogers cited two cartoons in which many readers were unclear on the idea that satire does not always imply agreement.

The first, he said, passed muster with his regular Pittsburgh readers who were used to his approach but created a firestorm in Oklahoma City, where a college paper printed it with the result that the editor was forced to resign.

The second, he said, drew fire from people who assumed that his message was, indeed, that African-Americans should be satisfied with a pair of Oscars, which — had that been the message rather than mockery of those who think that way — would indeed have been offensive.

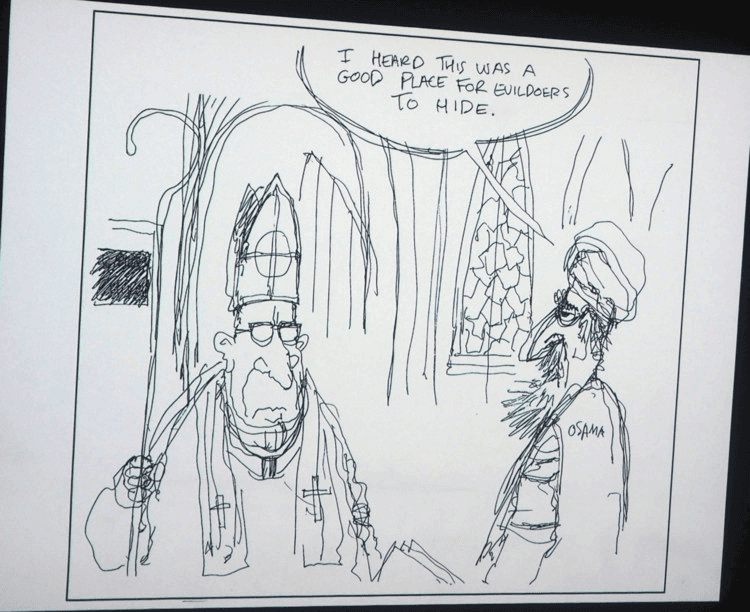

This intended commentary on the Roman Catholic Church’s sheltering of pederast priests as the US hunted for Osama bin Laden didn’t get past the initial sketch, and Rogers’ editors warned him to lay off the Church and Pope because they didn’t want more angry calls from the local bishop.

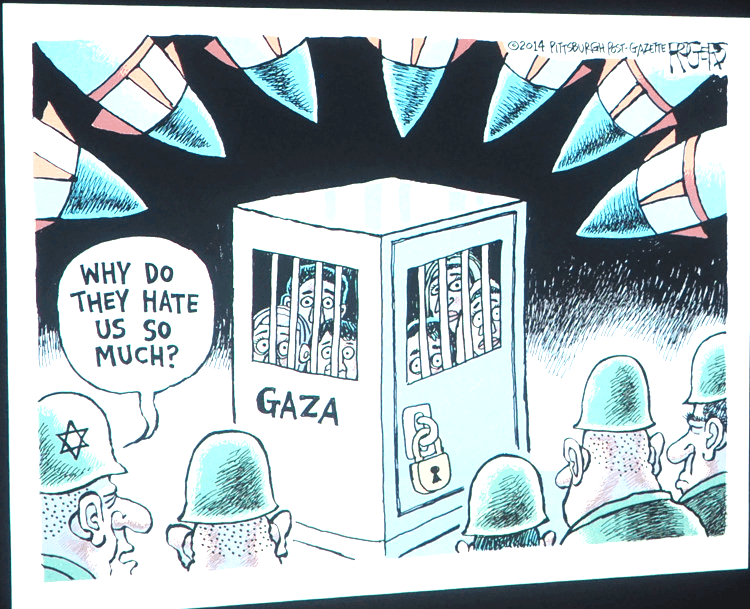

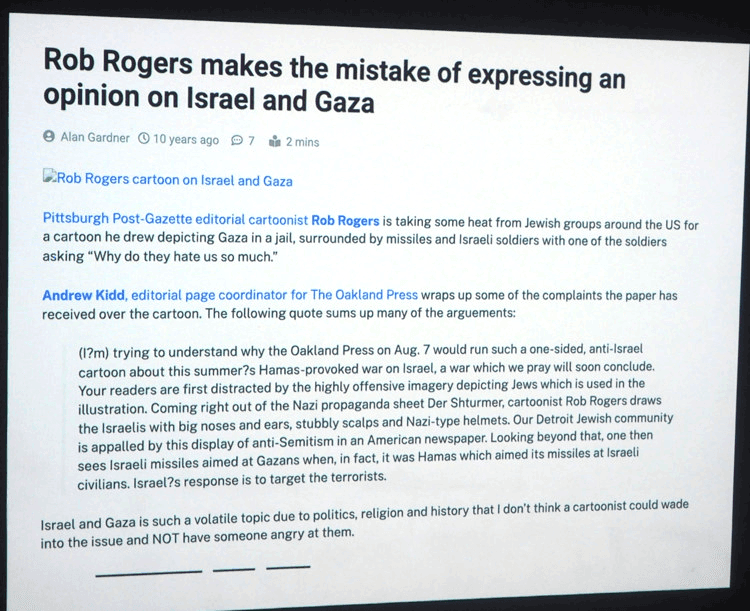

They also weren’t too happy with his commentary on Gaza, as my later-to-be-colleague Alan Gardner pointed out on this website.

Rogers said the defense that he draws everyone with a large nose made part of the uproar unfair, and he refused to see the jail cell as a cattle car harking back to the Holocaust, but he admitted that, if he had it to do over again, he’d have put Israeli flags on the helmets to indict that government, rather than using the Mogen David which shifts blame to the religion and its people.

But the friction between Rogers and his publisher continued, with more and more of his cartoons being spiked by the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette until he was finally fired, though in the Q&A that followed his presentation, he admitted to feeling more free now that he only deals with his syndicate rather than with editors at a home paper.

His adventure in censorship became a book, BTW.

Mr. Fish solved much of that matter by not working for a newspaper, marketing his work, rather, to congenial alternative publications, though he spent a decade working for Harper’s as well.

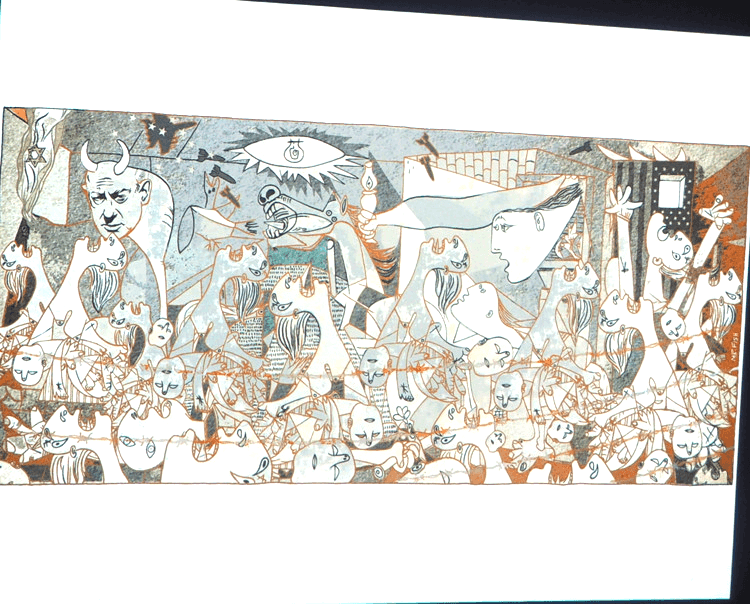

He wields a double-edged pen and said he likes detailed, finished art like this updating of Picasso’s Guernica because it makes people stop, pause and consider the piece, as opposed to a lightly drawn cartoon that engages them less deeply.

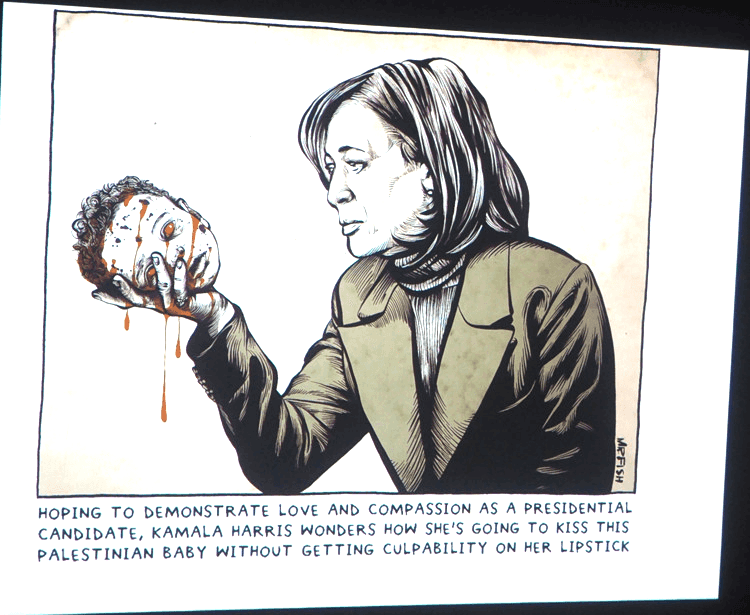

He noted that this harsh criticism of Kamala Harris is not intended to persuade anyone to vote for Trump, but rather to force engagement with her policies and approaches, avoiding the notion that one side has all the faults while the other is above reproach and reformation.

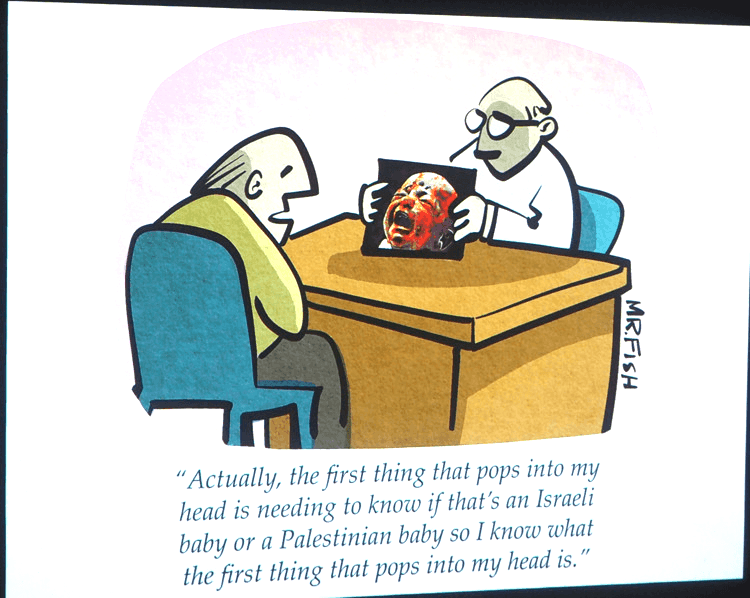

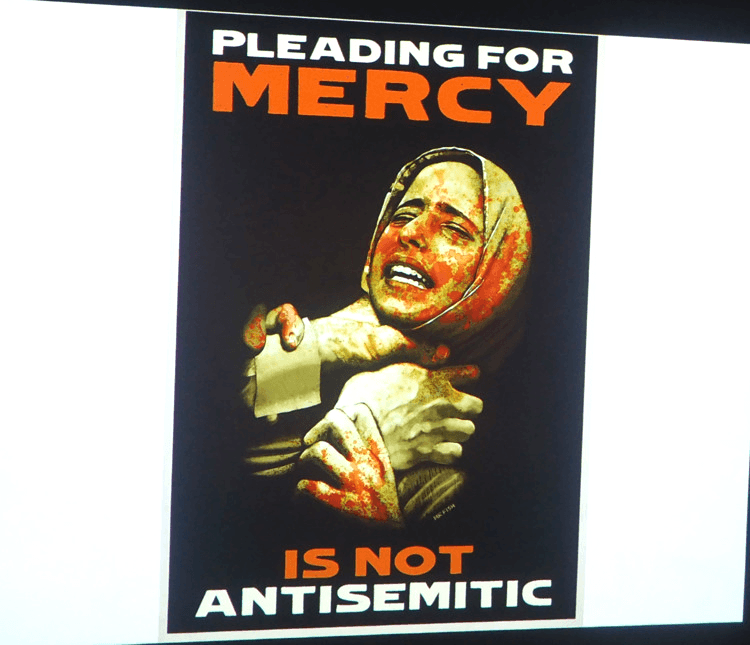

Not that he is opposed to drawing light graphics with explosive concepts.

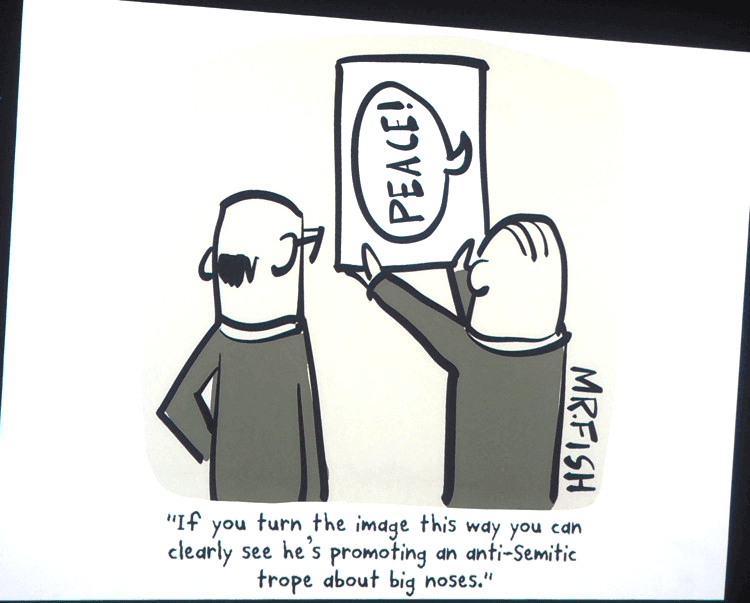

Including this one, which mocks those who search relentlessly for reasons to be offended.

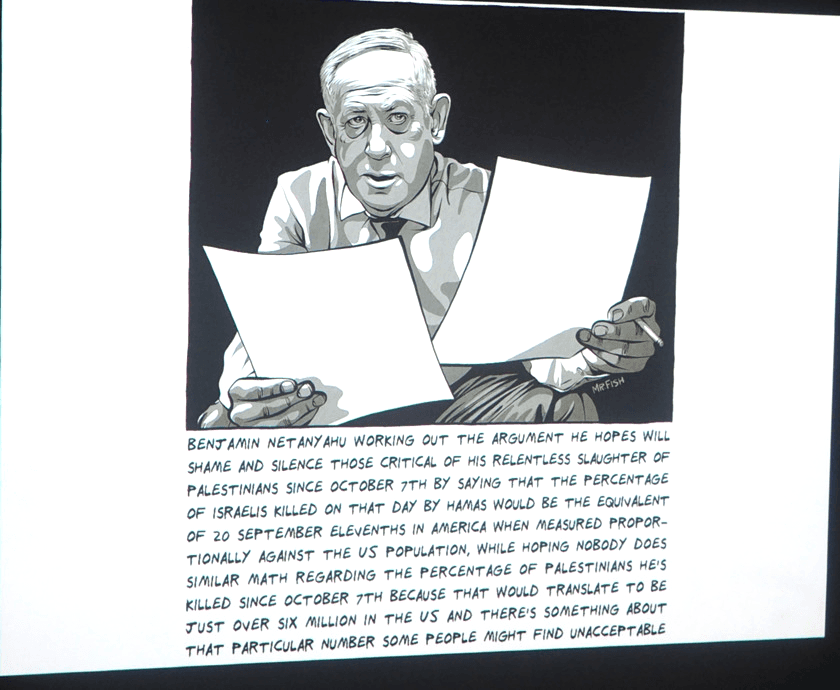

And he took particular pride in having done the math to discover that, when Netanyahu projected the deaths in the Oct 7 massacres to their proportion in the US population, projecting Gazan deaths the same way yielded a particularly unpopular figure.

But, again, finished art can stop the reader longer than a cartoon and provoke — that’s an appropriate word, “provoke” — deeper reflection.

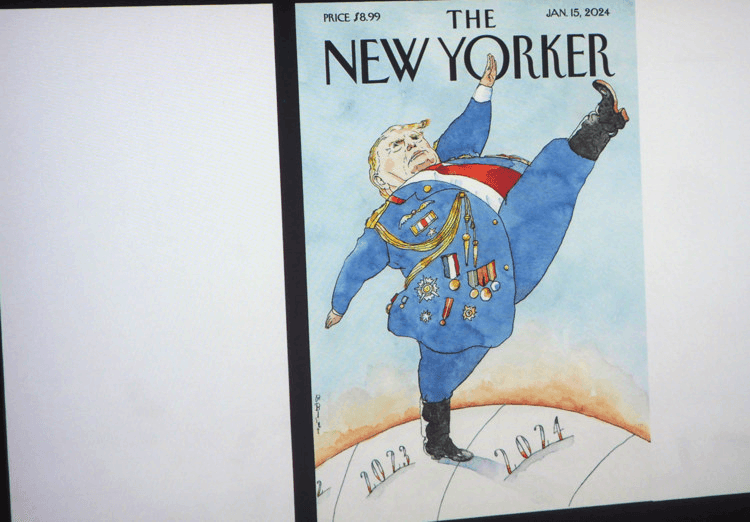

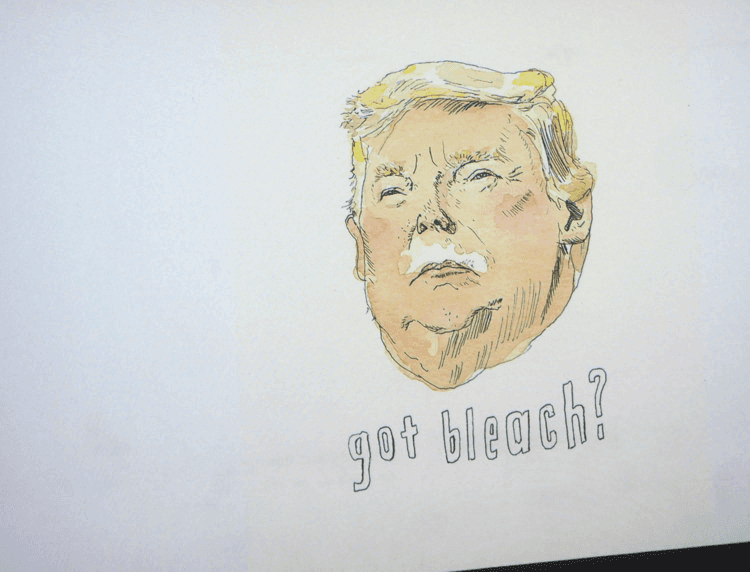

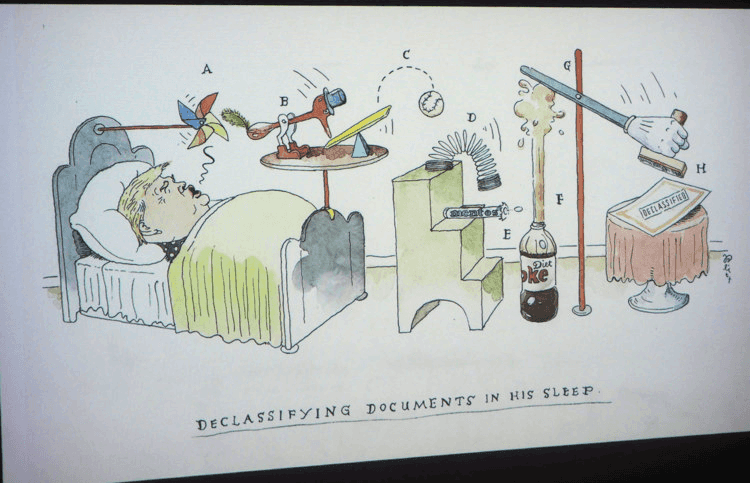

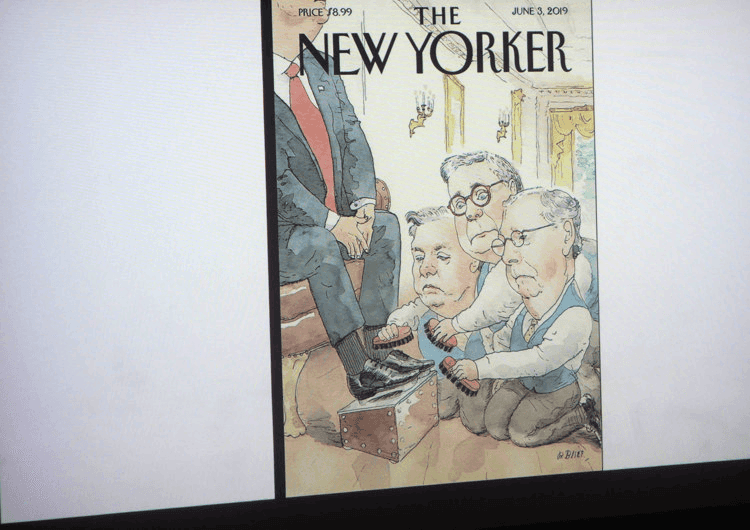

Having Barry Blitt close the day brought a combination of brilliant caricatures and some lighter, but no less penetrating, humor.

Some of what he offered was pure humor, though always with a satiric background.

But his ability to capture caricatures and expressions lifts even casual jokes to serious art, and he admitted how much he enjoys drawing these characters in the unfolding drama.

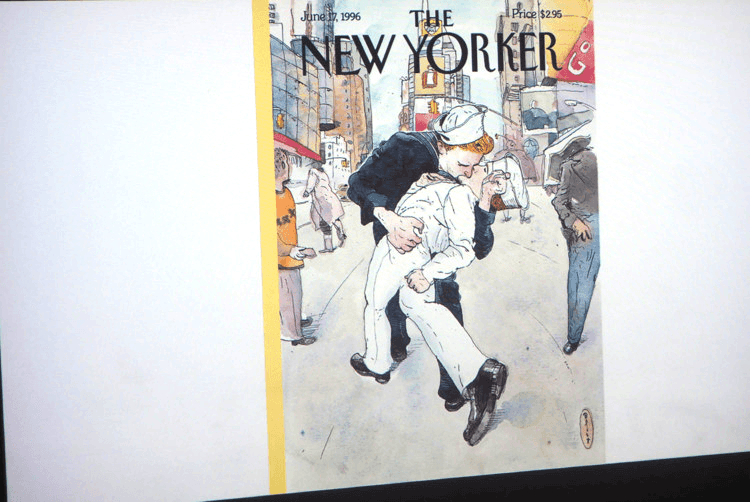

The New Yorker style also allows him to make commentaries, like this piece on same-sex marriage, with strength but not a bludgeon.

Note that his editor, Francoise Mouly, greenlighted his takeoff on Alfred Eisenstaedt’s famous VJ Day photo, sparing him the grief Jacques Goldstyn encountered above with a similar spoofing-but-serious commentary.

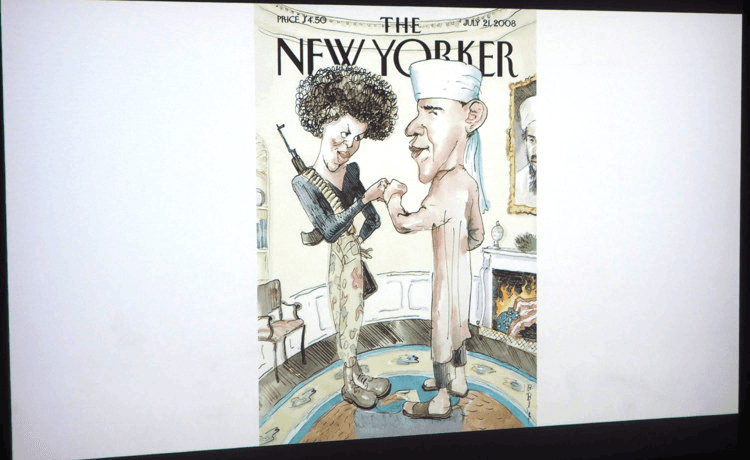

I was pleased that he included this infamous cover, reluctantly, admitting it had been an unsuccessful attempt at parody by which he “found out that the AOL mailbox only goes to 1,000 emails.”

The problem, IMHO, was not the satire on people’s misconceptions but the fact that, as a cover, it had no context to explain whether it was mocking those misconceptions or proposing them.

So it goes.

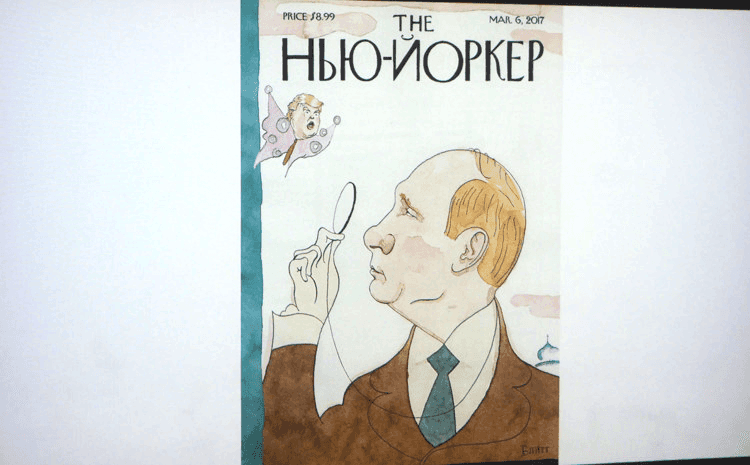

By contrast, this parody of the magazine’s Eustace Tilly mascot needs no context to make the commentary clear, though, Blitt explained, translating the magazine’s banner into Russian created issues with mailing it, since publications are required to have their names clearly legible.

He left that to the editors and distributors to figure out.

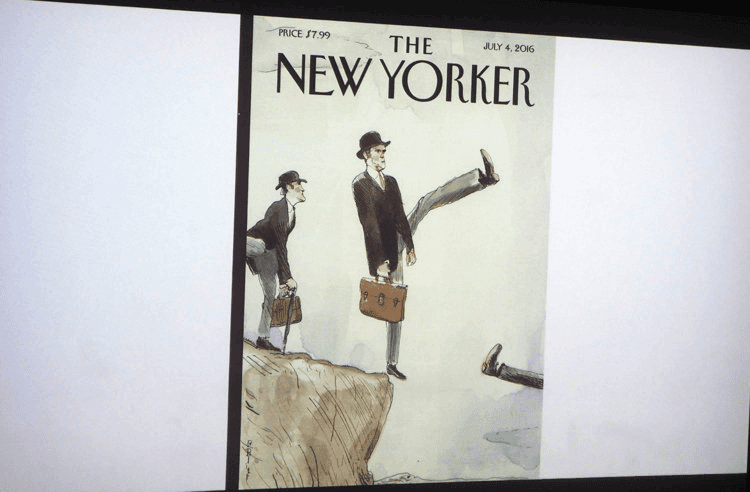

Then, when the news of the moment required a comment on Brexit, he turned to a familiar figure, and admitted that he had an easy job finding a model, since someone had given him a Ministry of Silly Walks gag watch.

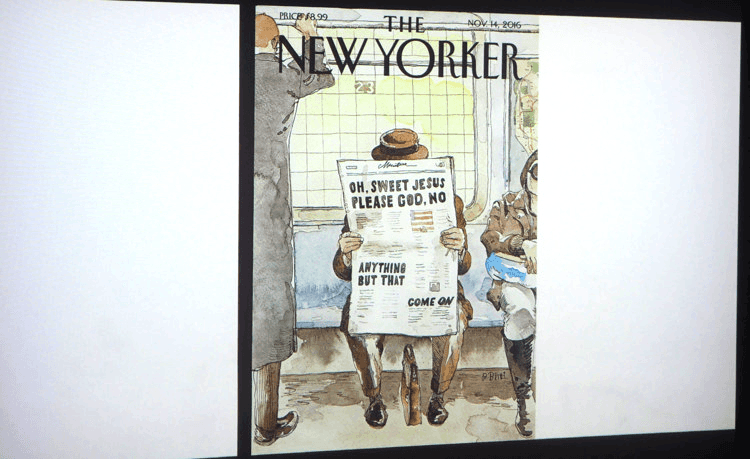

And while Serge Chapleau had done two debate cartoons so editors could choose the correct one for the next morning’s paper, Blitt’s deadlines didn’t allow for a switch depending on how the 2016 election came out, so he crafted a cover that would work under any circumstances.

“I knew half the country was going to be pissed off,” he explained.

And so to beer, wine and finger-food at the end of a jam-packed day.

Tune in tomorrow!

Comments 11

Comments are closed.