A Classic’s Centennial: Little Orphan Annie

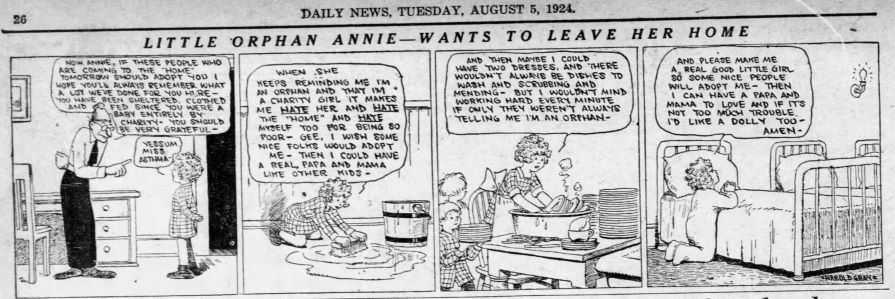

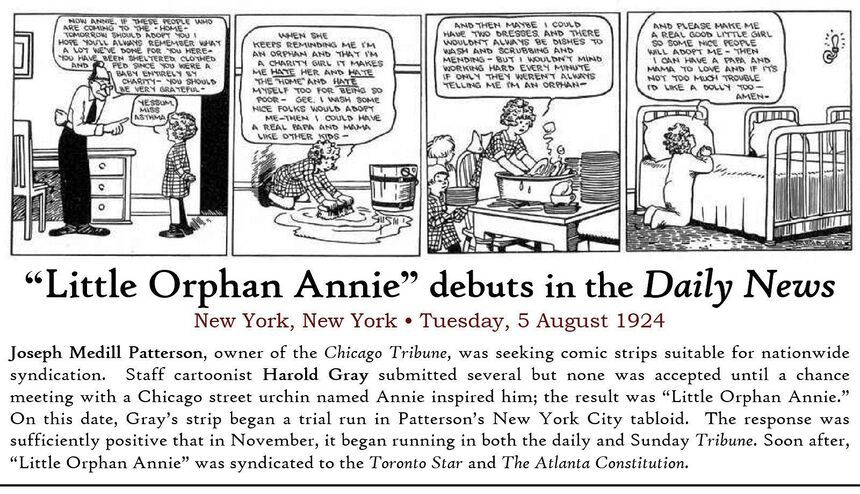

Skip to commentsOne hundred years ago in the pages of The New York Daily News …

The world, or New York anyway, was introduced to the spunky Little Orphan Annie by Harold Gray.

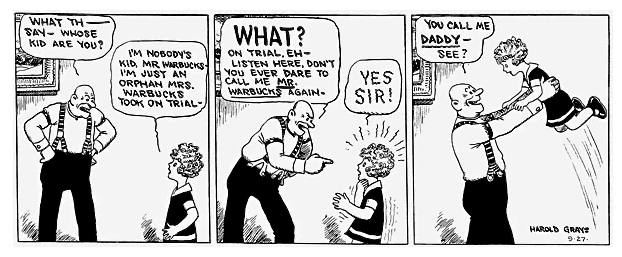

Not too far in the future Annie would meet “Daddy” Warbucks and, off and on, be a part of his household.

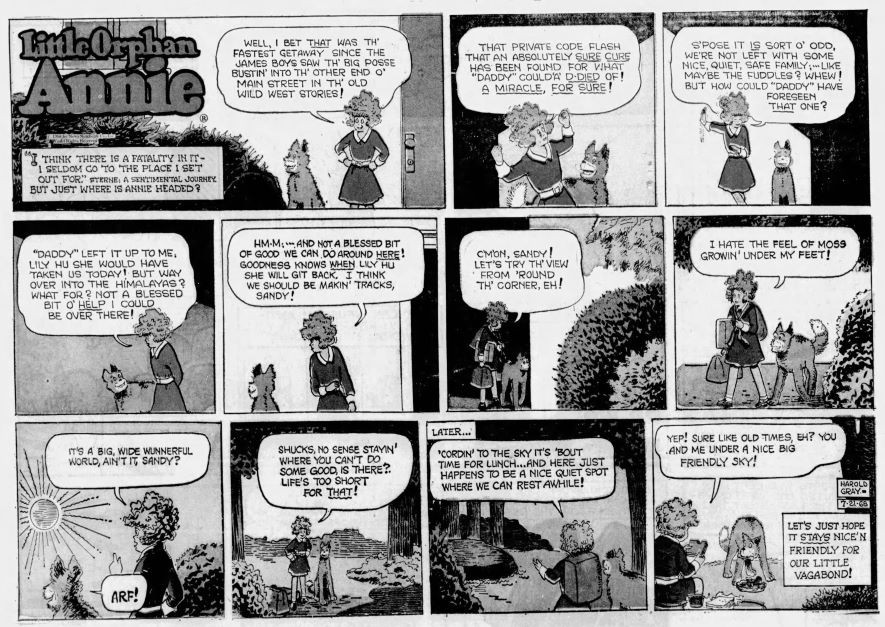

Within a month of that September 27, 1924 meeting Annie would be separated from “Daddy” in what would prove to be a continuing problem. However early in the new year Annie would befriend someone who would be her constant companion for the rest of her comic strip life.

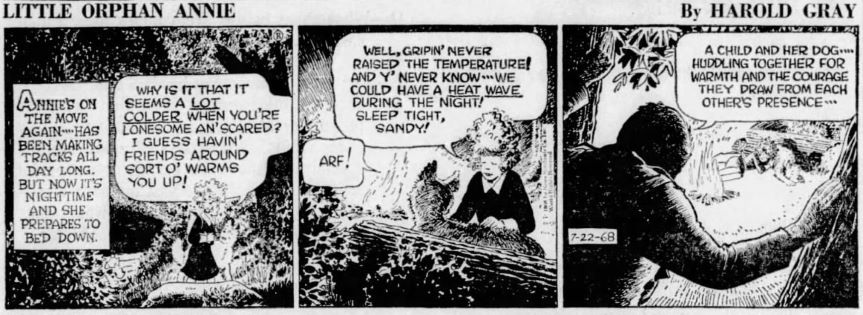

Sandy is first seen on January 5, 1925. Arf!

So the core of the cast is set and the already popular comic strip would go on to be an undisputed classic.

For those few unaware DerikBadman does a wonderful job of summarizing the strip in his 2005 review of the (highly recommended) 1970 hardbound collection Arf! The Life and Times of Little Orphan Annie, 1935-1945:

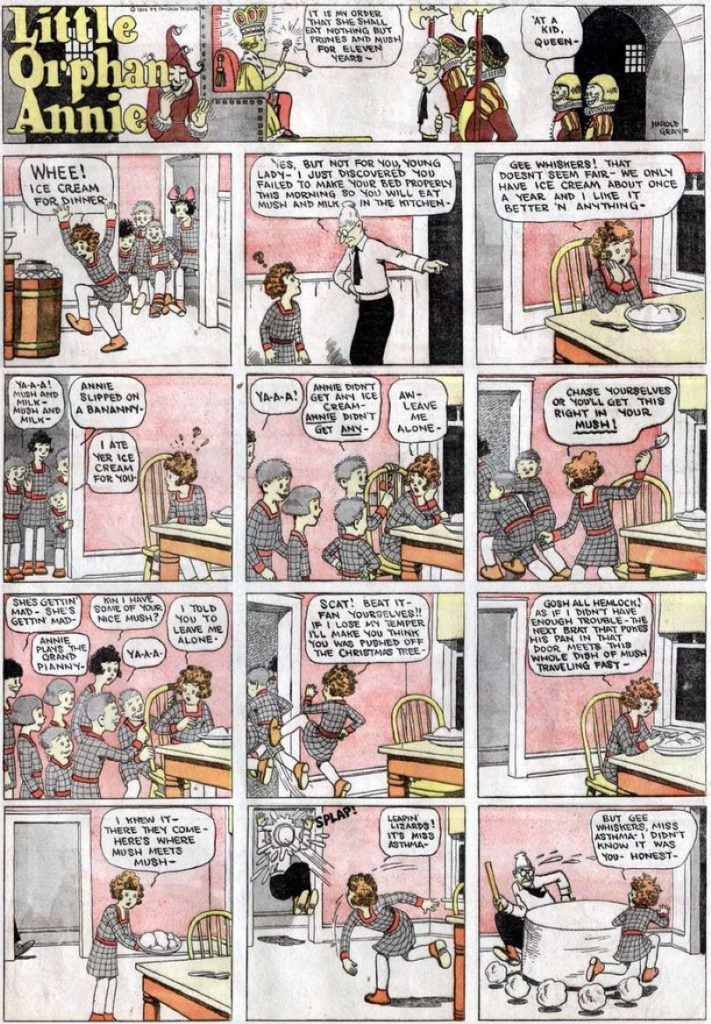

Annie is an orphan, who’s brave, self-reliant, and kind. Her constant companion is her dog Sandy (who in Gray’s art looks like some kind of lynx/monster with a ceaseless grin). She lives with Oliver “Daddy” (always in quotes) Warbucks, a extremely wealthy capitalist businessman, who talks a lot of libertarian philosophy (but in a down home kind of way) about hard work and spreading the wealth around (in the first sequence his new factory is successful so he raises the pay of all his workers and gives them better benefits, instead of taking it all himself). Oddly, Warbucks never seems to have a home; he is always on the go or staying with someone else.

The stories follow a predictable but oddly never dull cycle: “Daddy” goes away, often on a business journey, though later the war intervenes, as well as kidnappings, and other troubles; Annie–no matter where “Daddy” leaves her–ends up embroiled in trouble or is left to fend for herself; “Daddy” returns–often in time to save the day; “Daddy” and Annie solve the current situation, perhaps get into more trouble, often while vacationing; and then “Daddy” goes away again. This sequence happens quite a few times over the course of this book, always with some slight variation. In this way Gray offers a constantly shifting set of characters (the only other consistently reoccurring characters in what I read were Warbucks’ mysterious companions “Punjab” and “The Asp”) and settings (from small towns and farms to big cities to islands to castles).

DerikBadman continues:

Harold Gray is well-known as very conservative in his politics and this comes out quite clearly in the strip. The virtue of hard work and the ability of anyone to make it big if they just work hard enough is brought up numerous times. Other themes he returns to include: the gullibility of the public, gossip, the willingness of people to help each other out because they are “good folks”, and often the need to break the law for the right reasons. Warbucks serves as a model of the caring billionaire who’s always helping others out while following his rather strict code. I find the politics often distasteful, but it doesn’t take away from the success of the comic.

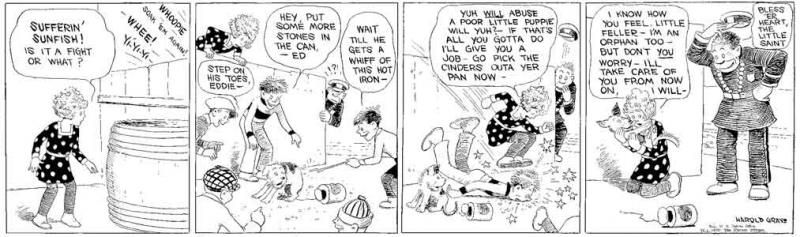

Gray’s art is cruder than most strips. He’s no Caniff or Raymond. Nor is he a Schulz or Segar. Gray’s characters are kind of stiff. We mostly see them from the waist up, rarely see feet. The action is all done with a very non-active drawing style. When he does illustrate some kind of activity (Annie punching a bully see below) it tends to look out of sorts…

The more I look at the art, the more I appreciate it. It’s deceptive at first glance, rough and stiff, yet, it so smoothly conveys all that needs to be conveyed both plot-wise and emotionally.

And it would go until Harold Gray’s death in 1968.

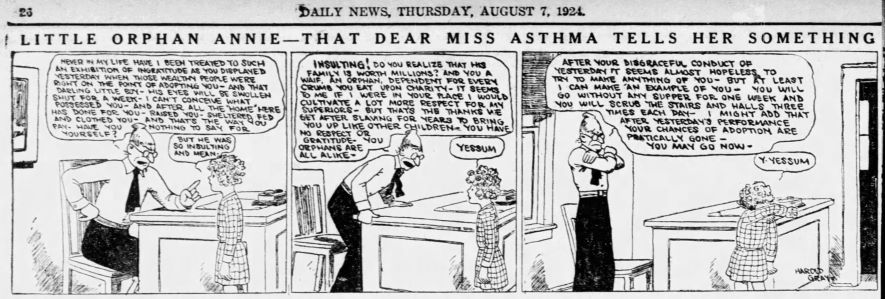

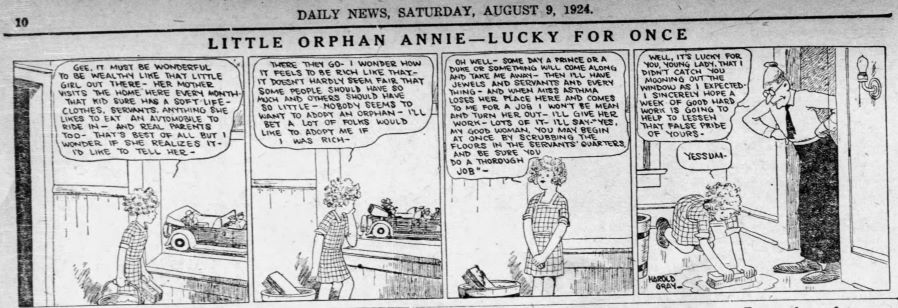

From the very first strip, which debuted today, ninety six years ago in the New York Daily News, Harold Gray established the emotional tenor that would distinguish Little Orphan Annie. Compared to the elaborate and carefully-conceived novel-length narratives Gray created in the 1930s and 1940s, the early Annie strips might seem a bit crude: the drawings are roughhewn (although his line fluid), the plotting has a shambling, seat-of-your-pants haphazardness, and there are occasional longueurs as Annie dawdles around while Gray waits for the next bit of inspiration to hit.

But the main components of the strip are there from the start: at the heart of the series is Annie, much-abused but spunky enough to fight back with a sharp tongue and a good left hook.

For those wanting to know more comics historian Jeet Heer at LitHub details the early life of Harold Gray and how that would form the philosophy he would bring to his Annie in The Complex Origins of Little Orphan Annie.

Harold Gray was thirty years old when he created Annie and, despite the occasional storytelling misstep and moments of uncertainty, he knew what he was about. This confidence came from the fact that Little Orphan Annie didn’t just spring up full-blown in a fit of wild inspiration. Rather, the strip was the culmination of many years of hard work and ambitious planning. Everything in Gray’s early life—his family background and upbringing, his schooling and military service, his wide-reading and early career—went into the making of Little Orphan Annie. Like his famous creations, Gray was a fighter and a straight-shooter. To look at his life is to see the foundation and building blocks of his work.

But the strip did not end with Gray’s death, the syndicate hired cartoonists to continue the strip.

Long ago I tried to determine Gray’s assistants on the strip, the ghost artists who worked on the strip from 1968 to 1974, and list those who were allowed to sign the strip beginning in 1974 (corrections encouraged):

LITTLE ORPHAN ANNIE/ANNIE

daily: August 5, 1924 – June 12, 2010

Sunday: November 2, 1924 – June 13, 2010

HAROLD GRAY

creator/writer artist

dailies: August 5, 1924 – July 20, 1968*

Sundays: November 2, 1924 – July 21, 1968*

*These would be the last strips that carried the

Harold Gray signature. July 21 is pretty universally

tagged as the last Gray Sunday, but July 20 not so

with the dailies. The CSC archives contain a list by

Bill Slankard that gives May 9, 1968 as the last Gray

daily. Any confirmation on that?

[The CSC is a Yahoo Group.]

EDWIN W. (ED) LEFFINGWELL

art assistant ????? – 1936

ROBERT (BOB) LEFFINGWELL

art assistant 1936 – 1968

ROBERT LEFFINGWELL

artist? writer?

1968? – 1968?

Some say that Leffingwell attempted to continue the

strip for the syndicate and they quickly realized he

didn’t have the talent to do the strip.

Others say that upon Gray’s death the strip was immediately

taken over by CT-NYN Managing Editor Henry Raduta

and CT-NYN staff artist Henri Arnold.

Comics historian Jud Hurd, a friend and neighbor of

Gray’s in the years leading up to his death, has

written that, “Bob Leffingwell…was no longer

involved with the strip after Gray’s death.”

HENRY RADUTA

writer

1968 – 1968

No start or stop dates.

Did he write for Leffingwell?

Did he and Arnold start straight off Gray?

HENRI ARNOLD

artist

1968 – 1968

Again, no start or stop dates.

ELLIOT CAPLIN

writer

daily: 1968 – August 18, 1973

Sunday: 1968 – August 19, 1973

No exact start dates.

End dates sussed from Bill Slankard’s

credits given in the CSC archives.

Conventional wisdom has Elliot Caplin as the

writer during the Tex Blaisdell years, but I have

him listed as “assistant writer” and Jerry Caplin

as “co-writer”. Unfortunately I no longer have a

source for this attribution. But Elliot had his

hands in many projects and it is not out of the

realm of possibility that he enlisted the help of

his brother. Still I can’t confirm.

PHILIP ‘TEX’ BLAISDELL

artist

daily: July 22, 1968 – December ??*, 1973

Sunday: 1968 – December ??*, 1973

The daily start date is again from the Slankard post.

If true then it would mean that the earlier team of

Raduta and Arnold were continuing the strip under

Gray’s signature.

Ironically, famous background artist Blaisdell was

assisted here on backgrounds by Annette Lee Marrs

(1968) and Paul Kirchner (1973).

Lee Marrs source is from some interview, IIRC,

no source for the Kirchner credit.

*Unsure if Tex Blaisdell went all the way through December 1973.

MICHAEL FLEISHER

JOE ORLANDO

writers

daily: August 20, 1973 – February 5, 1974 (a Tuesday)

Sunday: 1973 – February 3, 1974

Start date courtesy Slankard.

I have tied Fleisher and Orlando together.

Orlando’s credit on LOA has not been consistent

through the years. (A typo on the Bails’ Who’s Who

site has led to a number of sites crediting Orlando

as the writer of the strip in 1964.)

My notes have the two together with Fleisher as writer

and Orlando as “editor/co-plotter/continuity”.

Again – no source.

VIC MARTIN

artist

daily: December 31, 1973 – February 5, 1974 (a Tuesday)

Sunday: December 30, 1973 – February 3, 1974

Before moving on to David Lettick, some more names…

ALLEN SAUNDERS

Jerry Robinson, in his The Comics, credits the Steve

Roper writer as “story consultant”. Robinson does not

say who he consulted. Leffingwell? Raduta? Fleisher?

BILL WILLIAMS (ALFRED O. WILLIAMS)

and

WINSLOW MORTIMER

A 1974 Washington Post article introducing David Lettick

as the new creator of LOA lists all the previous

contributors since Gray. He names these two, but doesn’t

say what they did or with who they did it.

BILL WRIGHT and BEN ODA

Leiffer and Ware’s Comic Strip Project list

these two as letterers during the post-Gray years.

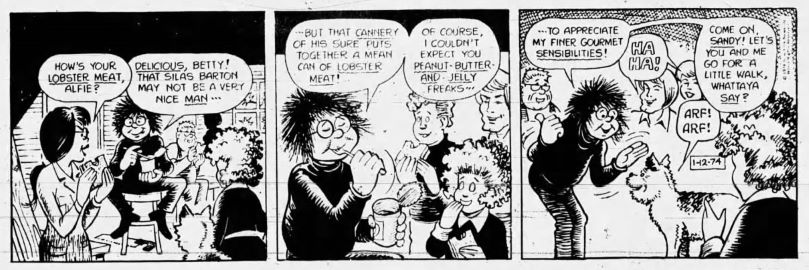

DAVID LETTICK

writer/artist

daily: February 6, 1974 (a Wednesday) – April 20, 1974

Sunday: February 10, 1974 – April 21, 1974

Source – The Lima News

David Lettick was the first contributor allowed

to sign his name since the last Harold Gray signature.

HAROLD GRAY REPRINTS

daily: April 22, 1974 – December 1, 1979

Sunday: April 21, 1974 – December 2, 1979

The April 21, 1974 Sunday strip was split between the

end of Lettick’s run and the beginning of the Gray reprints.

A list of the original runs of the Gray reprints is here.

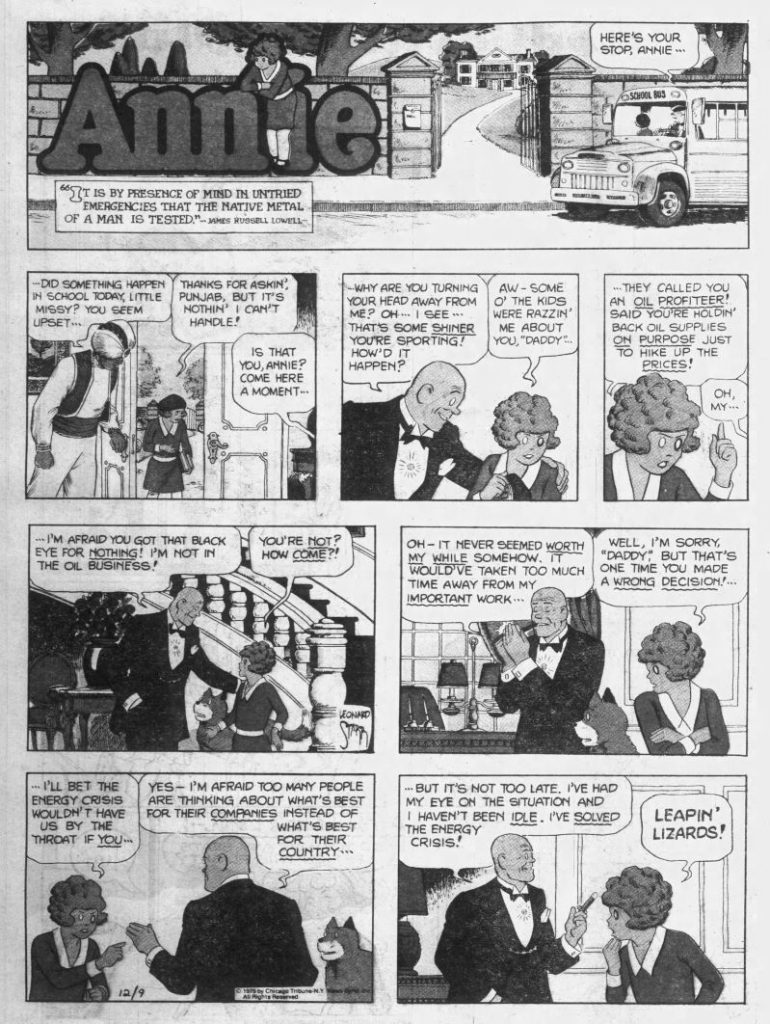

LEONARD STARR

writer/artist

daily: December 3, 1979 – December 8, 1979

This week of dailies transitioned from the Gray reprints

to setting up Starr’s run.

Listed separate from the rest of Starr’s tenure on the

strip because I believe this week was still officially

published under the title “Little Orphan Annie.”

LEONARD STARR

writer/artist

daily: December 10, 1979 – February 19, 2000

Sunday: December 9, 1979 – February 20, 2000

With the December 9 entry the strip is officially

(I think) retitled “Annie”.

The Comic Strip Project lists “Frank Bolle, Jr.” as

Starr’s art assistant (backgrounds) for 9 years,

and Susan Fox as letterer during the 1990s.

I have Frank Bolle as letterer from 1986 – 1994.

Starr is quoted as saying that Bolle “pencilled a

sequence from my roughs.”

LEONARD STARR REPRINTS

daily: February 21, 2000 – June 3, 2000

Sunday: February 27, 2000 – June 4, 2000

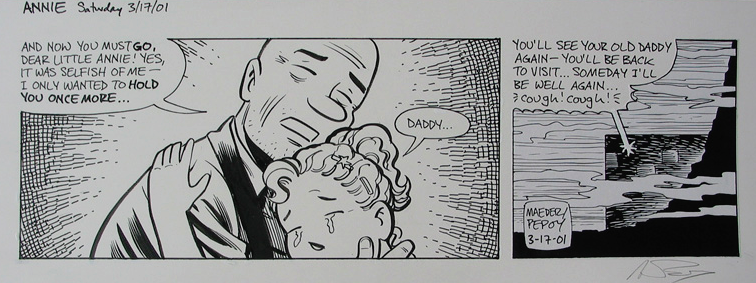

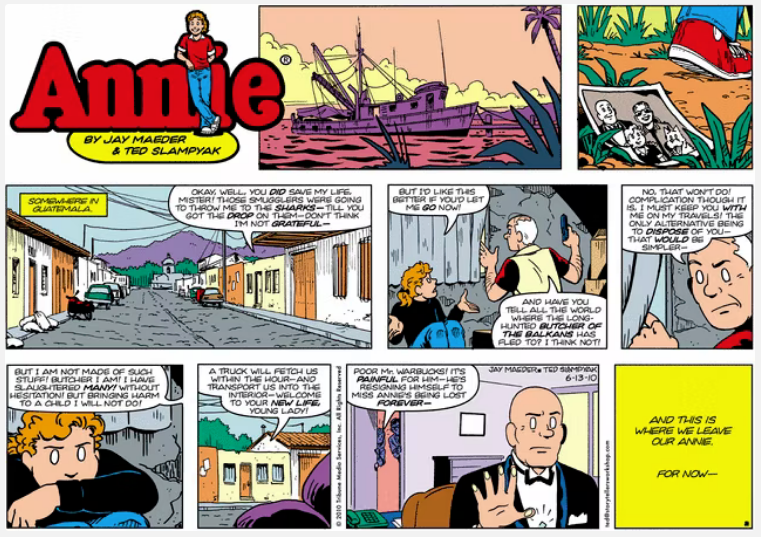

JAY MAEDER

writer

daily: June 5, 2000 – June 12, 2010

Sunday: June 11, 2000 – June 13, 2010

ANDREW PEPOY

artist

daily: June 5, 2000 – March 31, 2001

Sunday: June 11, 2000 – April 1, 2001

Pepoy also, supposedly, retouched the May 27, 2000 Len Starr reprint.

Some Pepoy Annies (along with Blaidell and Lettick) here.

ALAN KUPPERBERG

artist

daily: April 2, 2001 – July 3, 2004

Sunday: April 8, 2001 – July 11, 2004

TED SLAMPYAK

artist

daily: July 5, 2004 – June 12, 2010

Sunday: July 18, 2004 – June 13, 2010

The Maeder/Slampyak strips are currently being posted at GoComics.

With Mike Curtis taking over Dick Tracy Annie has become an occasional guest star at that strip.

When Little Orphan Annie came to an end comics historian R. C. Harvey wrote a history of the strip.

On May 13, 2010, Tribune Media Services announced its intention to stop production and distribution of one of cartooning’s iconic creations, the newspaper comic strip Little Orphan Annie. The resilient redheaded teenager made her last appearance in the nation’s newspapers on Sunday, June 13, just two months shy of celebrating an 86-year run. But the longevity, while notable, is deceptive: the strip foundered badly after the death of its creator, Harold Gray, in 1968, and while one of Gray’s successors righted the craft for two decades, Annie never again achieved the circulation or cultural status it enjoyed in Gray’s hands, proving yet again that a comic strip, uniquely the product of individual inspiration, usually cannot survive the death of its creator. And Gray’s strip was more idiosyncratic than most.

Comments 2

Comments are closed.