First And Last: Tim Tyler’s Luck

Skip to comments

Among the comic strips that became public domain this year was Tim Tyler’s Luck by Lyman Young.

Tim Tyler’s Luck, the most famous comic strip created by cartoonist Lyman Young, was well established at King Features Syndicate by the time his brother, Chic, also a cartoonist, got his own prominent King Features strip going. And yet, today, Lyman Young’s biggest claim to fame in the cartooning community is the fact that his younger brother created Blondie.

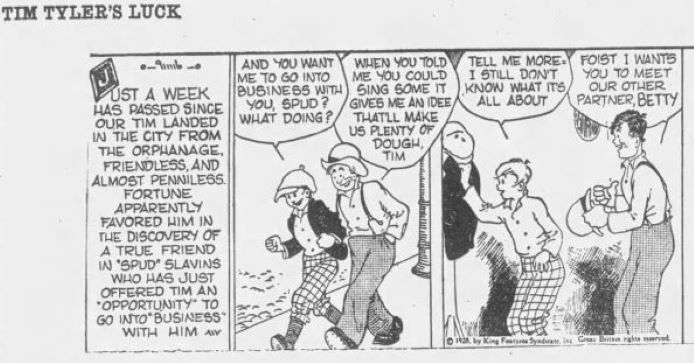

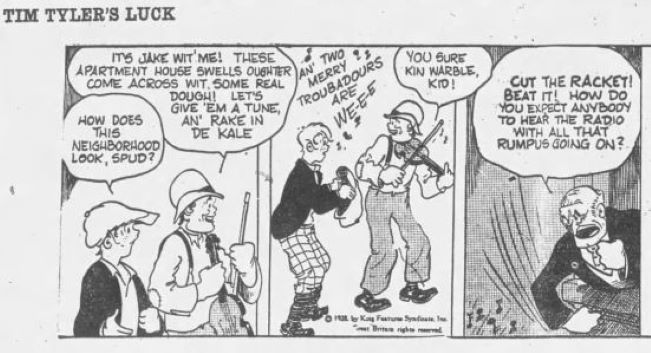

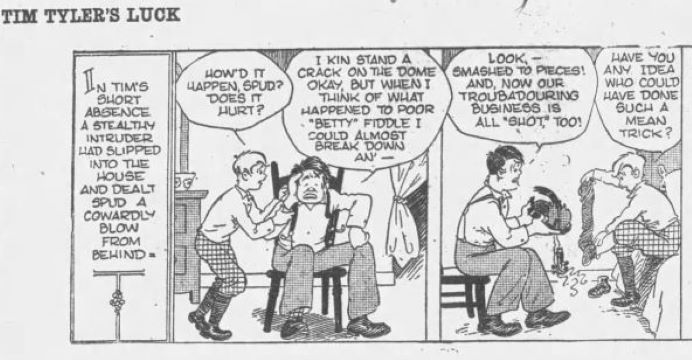

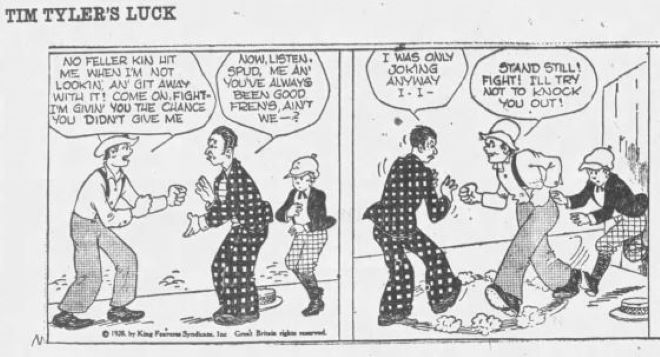

Tim debuted on August 13, 1928, with the title character living in an orphanage, just as Little Orphan Annie had done almost exactly four years earlier, and Little Annie Rooney a good deal more recently. Like Annie (both of them), he quickly left the orphanage and took off on his own. Unlike Annie (both of them), instead of a dog as his constant companion, he had a human being, an older boy named Spud. By the time the Sunday version started (July 19, 1931), Tim and Spud were well away from the orphanage, living a life of adventure.

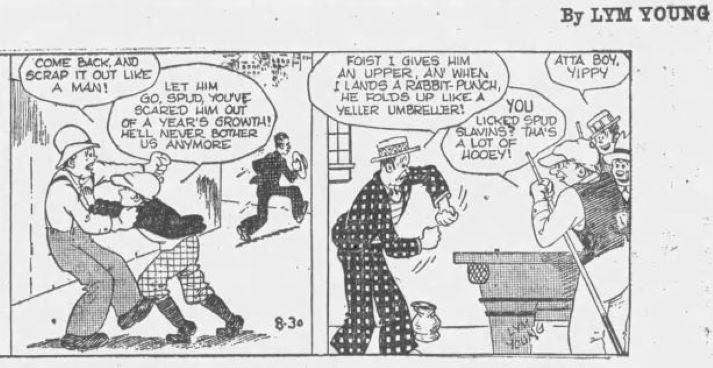

Below the first few weeks of Tim Tyler’s Luck by “Lym” Young from August 1928 as taken from the Dziennik Dla Wszystkich, Buffalo, New York’s Polish language newspaper, via newspapers.com.

More from Don Markstein:

At first, their adventures tended to be light and cartoony, but later, with Buck Rogers, Dick Tracy and the like gaining popularity, the strip took a more serious turn. Tim and Spud traveled the world before settling for several years in Africa, where (having grown into their late teens or so) they joined the Ivory Patrol and spent their time chasing after poachers and the like. They returned to America during World War II, where they mostly dealt with spies and saboteurs. Afterward, they went traveling again, eventually returning to Africa, where they remained for good.

Granted Tim Tyler’s Luck didn’t have the blood and guts of Dick Tracy or the all-out pow-boff of Captain Easy but, as the strip below from the strip’s second month of 1928 shows, Young didn’t wait until The Adventurous Decade of the 1930s to get Tim and Spud into some serious action.

The Grand Comics Database details the writers and artists that worked on the strip throughout its run:

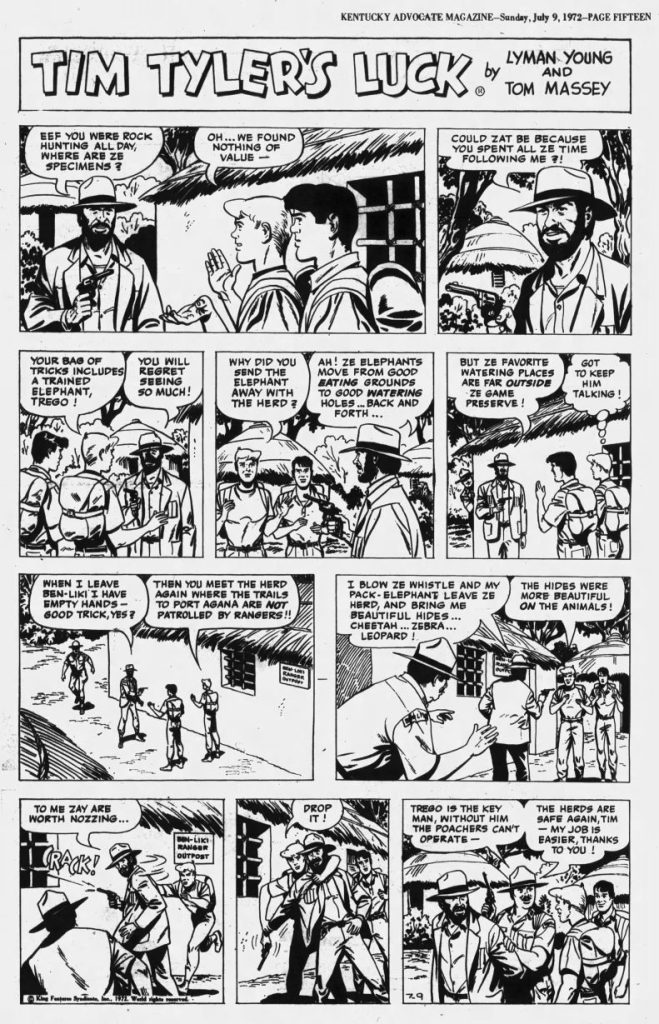

Lyman did the daily and Sundays from the beginning until his son Bob Young took over the art on the daily strip on June 23, 1952. Tom Massey officially took over the art on the Sunday strip on July 6, 1952, and continued on it until the Sunday ended on July 9, 1972.

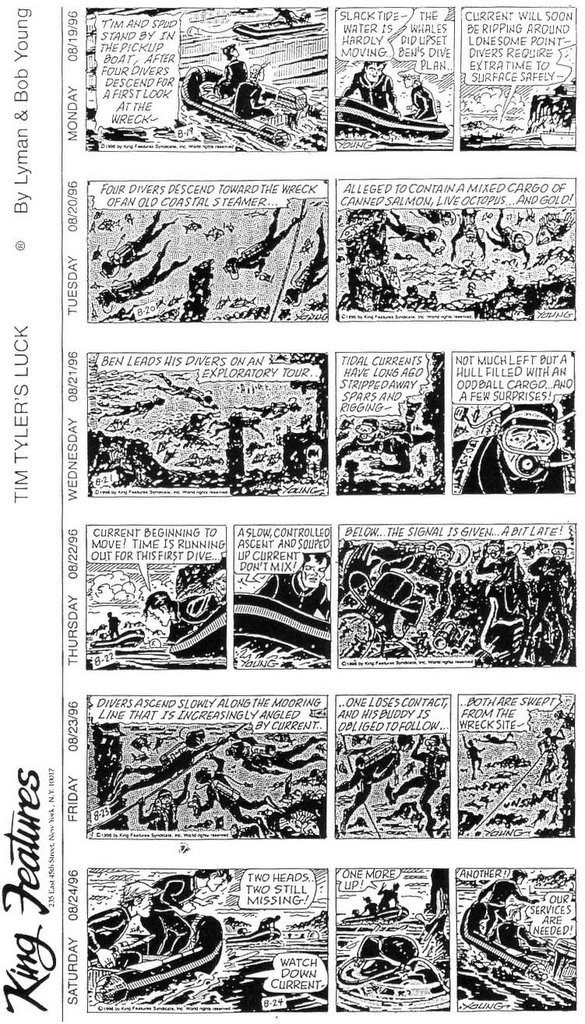

Jim Young

, another son of Lyman,[Jim and Bob Young are one and the same] did the artwork on the daily strip, from 1972 to 1978. Bob Young then returned to do the art for the daily strip from 1978 until the strip’s end on August 24, 1996.Lyman continued to write both strips until 1983. Bob Young wrote both strips from 1983 until it ended on August 24, 1996.

Tim Tyler’s Luck had many ghost artists who worked on this comic strip, known creators include Alex Raymond from 1932 to 1933, Burne Hogarth during early 1934, Charles Flanders on Sundays during 1934, Bob Naylor during the 1930s, Tony DiPresta lettering mostly during the late 1930s, Alden Williams during the early 1940s, and Nat Edson who was the primary ghost artist from the mid-1930s to the mid-1940s.

Further ghost credits known are Clark Haas doing daily art from November 5, 1945, to August 30, 1947, and Sunday art from January 13, 1946, to August 24, 1947. Tom Massey ghosted daily art from September 1, 1947, to June 21, 1951, and Sunday art from August 31, 1947, until he was officially credited with the work on July 6, 1952.

The only recent reprint of the strip is the Alex Raymond ghosted comics of 1933.

A Sunday page ran from July 19, 1931 to July 9, 1972 (below).

Tim Tyler’s Luck disappears from any newspaper.com newspapers in 1986, but King Features continued syndicating it until August 24, 1996 when it was appearing in only one U.S. newspaper. Allan Holtz can think of two reasons that it continued that long in a post that shows the last strips from a King Features proof sheet:

I no longer recall where I heard this, but the rumor was that the strip continued for so long for two reasons. First, Lyman Young was Chic Young’s brother, and King Features didn’t want to offend cash-cow Blondie creator Chic by dumping his brother. Second was that supposedly the strip was still popular in some foreign markets, making it (barely) profitable enough to continue production.

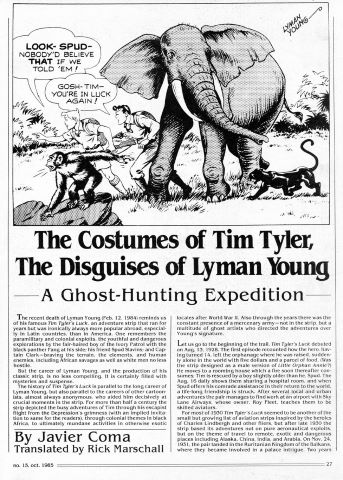

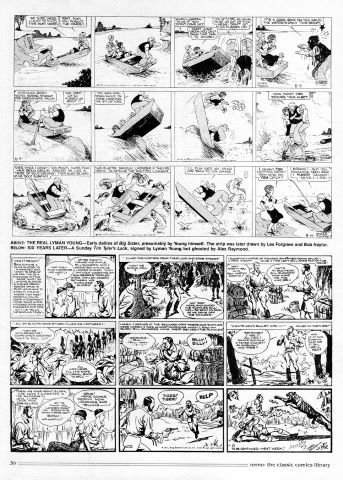

For further reading dig out your copy of NEMO: The Classic Comics Library #15.

Comments

Comments are closed.