John Adler – RIP

Skip to commentsHarper’s Weekly compiler/indexer and Thomas Nast biographer John Adler has passed away.

John Adler

September 29, 1927 – June 11, 2024

From the Sarasota Herald Tribune obituary:

John Adler, 96, passed away June 11, 2024 in Greenwich, CT.

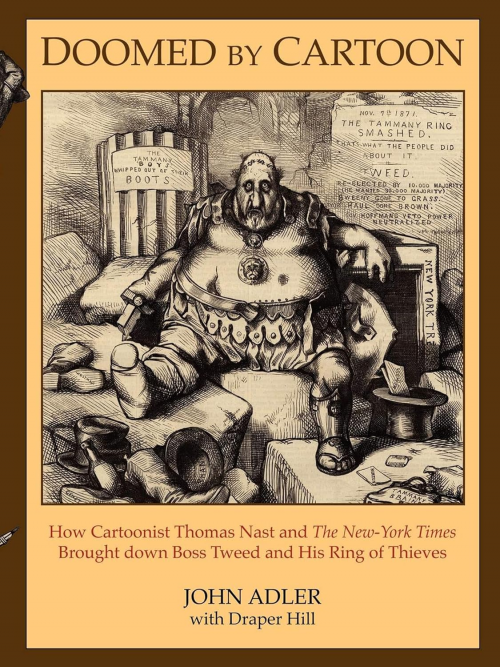

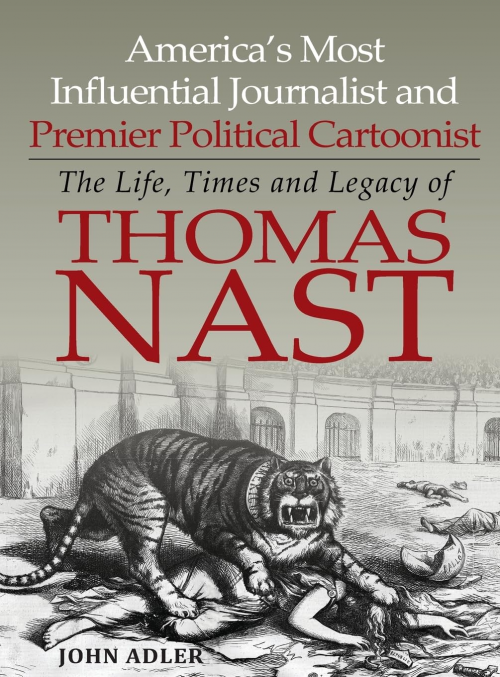

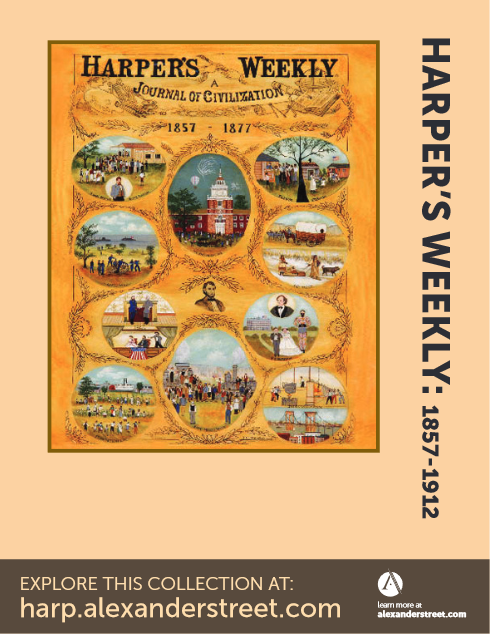

In the early 1970’s John acquired a full set of Harper’s Weekly Magazines (which were published between 1857 and 1912). He ultimately had all 73,000 pages of them manually indexed, over a period of twelve years, creating the HarpWeek database that is now used in more than 500 colleges, universities and libraries. Harper’s Weekly published many Thomas Nast cartoons, and John became a Nast expert and went on to write and publish two books about Nast, “Doomed by Cartoon: How Cartoonist Thomas Nast and The New York Times Brought Down Boss Tweed and His Ring of Thieves” (2008), and “Thomas Nast: America’s Most Influential Journalist” (2022) [link added]. For his work on HarpWeek John was awarded the E-Lincoln Prize.

From the John Adler-created ThomasNast.com website “about the author” page:

One day, he answered a New York Times ad for the sale of some duplicate annual volumes of Harper’s Weekly — America’s de facto “newspaper of record” from 1857 to 1912 — and soon found himself the owner of a complete set of fifty-six volumes.

As a retirement hobby, John decided to have all 2,912 issues manually indexed. John’s new company, HarpWeek LLC, manually indexed, scanned and retyped all 73,000 pages of Harper’s Weekly over twelve years, with a staff of as many as fourteen historians working on it. HarpWeek, his proprietary digital database, has been licensed to more than 500 academic institutions and public libraries worldwide. For this, and another database called Lincoln and the Civil War, John was awarded the 2003 eLincoln Prize in history, which included a copy of the bust of Lincoln in the Oval Office.

More from “About the Author:”

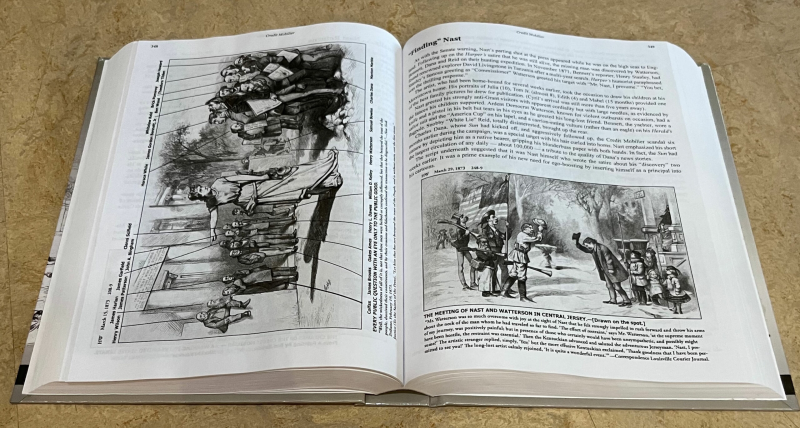

When he delved deeper, the artistry and political impact of Thomas Nast’s cartoons and illustrations totally captured his interest. Consequently, John had the indexers prepare a chronological listing of all Nast’s work, including their size and location within each issue. With help from the late Draper Hill, a political cartoonist and Nast historian, John was able to identify 445 of the 450 people whom Nast drew and have them indexed by name, topic and literary source, if any (e.g. Shakespeare by play and character).

These unique and exclusive compilations, along with relevant text, provided a complete visual record of Nast’s quarter-century at Harper’s Weekly. With them and the contextual HarpWeek database for a backbone, reporting and fleshing out Nast’s life and work objectively became much more doable.

In 2008, John published Doomed by Cartoon: How Thomas Nast and The New-York Times Brought Down Boss Tweed and His Ring of Thieves [link added].

John talks about indexing the 19th Century Harper’s Weekly for a 21st Century audience:

As a retirement project, I decided to have this uniquely important journal manually indexed. Harper’s Weekly never had a useful index, so until now there has been no way for students and researchers to access the illustrations, cartoons, news, literature, editorials, and ads that these volumes contain without spending hours poring over microfilm or locked-up original copies in rare book rooms of libraries. Harper’s Weekly is really the only consistent, comprehensive, week-to-week chronological record of what happened world-wide in the last half of the nineteenth century.

The reason for manually indexing Harper’s Weekly is to put nineteenth century language, occurrences and illustration content into twenty-first century terminology. For example: Should the 1858 New Jersey lady who owned a pistol be allowed to keep it? We index that item under “Women’s rights,” although the term was not used in the 1858 article’s content.Since 1995, up to 12 indexers with advanced degrees have read every word and studied every illustration and cartoon in Harper’s Weekly, and have carefully constructed user-friendly indexes that will guide you in locating information quickly and concisely.

John’s monumental undertakings in regard to both Harper’s Weekly and Thomas Nast

are historical feats for which present and future generations will be eternally grateful.

Our thoughts are with John’s family and friends.

Comments 3

Comments are closed.