CSotD: Where nobody knows your name

Skip to comments

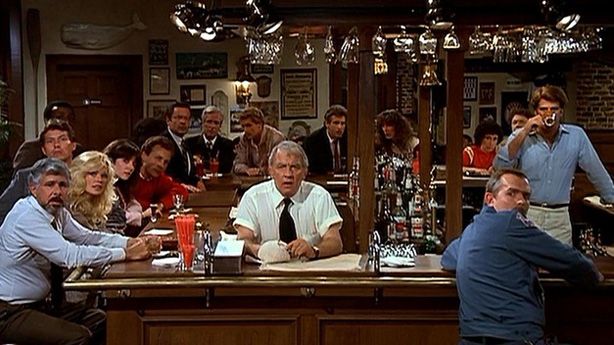

(photo: NBC)

With all due respect, they got it wrong. When Cheers was taken over by a corporation, they brought in Rebecca Howe and she was the boss and eventually Sam bought the bar back and he was back in charge.

Well, it was a comedy after all.

In the real world, as in the show, Sam would be kept on board, but from there on, reality would take over: Coach is offered a buyout because as the longest-serving employee, he’s paid the most. So they get rid of him and hire a kid named Woody at starters’ pay.

Then they find out that Sam and Diane have something going on, so they’re both forced to resign, and, despite several warnings from HR, Carla keeps insulting customers, so she’s gone. The new manager, Rebecca, does a pretty good job, so she gets promoted to the Cheers in Pittsburgh.

Which is exactly the same as the Cheers in Boston: Same signage, same decor, same menu, same monthly promotions, same everything.

It’s like an Applebee’s or a TGIF or a Bennigan’s, complete with rugby shirts.

It’s Chotskie’s with a liquor license, and plenty of flair.

Norm and Cliff have stopped coming in. Frasier drops in once in awhile because it’s near his office, but he just orders a sandwich and sits in the corner by himself.

You don’t wanna go where nobody knows your name.

The same thing has happened to your newspaper. Jack Ohman, former staff cartoonist for the Sacramento Bee, nailed it 31 years ago, when he was working for the Oregonian.

The mass firing of the McClatchy chain’s editorial cartoonists has gotten a lot of attention. DD Degg has chronicled it here and I’ve not only written about it but have been quoted about it a few places.

But it’s only a symptom. The disease is larger, more systematic and goes back to the changeover in Ohman’s cartoon.

I’ve worked in newspapers as a freelancer and as a staff reporter, and in 1992 I’d just moved into marketing as the Internet hit the industry, which gave me a front row seat not simply at the paper where I worked but at the chain level.

The simple explanation is that the few remaining dinosaurs on the left in Ohman’s cartoon were out-voted by the growing number of fine fellows on the right.

I remember one publisher who kept insisting that you couldn’t give content away for free. His objections were buried by those who said giving it away would work because we’d get clicks.

Almost none of them even knew what clicks were, much less how that would spell profits. But they’d read about it. They’d heard about it. They chose what to believe.

And when Craigslist appeared three years later, they were certain it would go away, so they did nothing.

Instead, classified ads went away and took nearly half our income with them.

There was a time when men like John Clum founded papers like the Tombstone Epitaph, though Clum only ran the paper for a few years, between his time as a historic Indian agent among the Apache and his popping up in Gold Rush Alaska with his pal, Wyatt Earp.

More of those entrepreneurs settled into their communities for the long run. In Clum’s day, they gathered the news and sold the ads, and, at the smaller papers, they also set the type and ran the press.

Even up to the 1990s, the publisher was often a curmudgeonly penny-pinching tyrant who was on the board at the Chamber, and at Rotary, and at the United Way, and pretty much everywhere else.

His wife had a flower show every spring, which meant that the reporters had to write stories for the special section that ran that week.

They hated doing that, but that special section was full of ads placed by the publisher’s buddies at the Chamber and at Rotary and at the United Way and pretty much everywhere else. It was payback, because he gave them space for their pet projects at other times of the year.

They bought ads throughout the year, too, because the business leaders of the community were his friends and colleagues.

That was then. This is now.

Today, a publisher is slotted into the chair by Corporate. If he’s any good, he — or she — is promoted within five years. If not, he — or she — is history in that same time period.

No publisher is ever around long enough to make a mark at the Chamber or Rotary or United Way or anywhere else.

Here’s something else: He may have been crusty and vulgar and sexist and maybe racist, too, but he enjoyed a good laugh, and if you showed him a comic strip, he got it.

And if you drew editorial cartoons that squared with his politics, you were golden.

But both editors and publishers have changed. That button-down fellow on the right side of Ohman’s cartoon doesn’t get it. Humor, sarcasm and innuendo don’t fit on a spreadsheet, nor do they follow the grammatical logic in the AP Style Book.

He’s not stupid. He’s just over-specialized.

I worked with editors and publishers on a daily basis for some 20 years, and tangentially for another 20. My estimate is that two-thirds of them did not understand cartoons. It’s perceptual, not intellectual, but it’s more prevalent now than it was when I started.

This is why, when a cartoon offends readers or when there is a change in the comic strip line-up, editors write these puzzled columns in which they muse over the angry letters and phone calls they get from readers who care about cartoons.

But while the old-school publisher or editor would accept that these things had to run in the paper because people were passionate about them, the new improved bean-counting manager still considers cartoons dispensable.

Which brings us back to Chotskie’s, where it doesn’t matter what is on the menu, because that decision is made at Corporate. What matters is how much flair you have on your suspenders.

Cheers has been turned into an Applebee’s, and the corner diner is now a McDonald’s, and you can’t get an ice cream soda at Rite Aid.

Newspapers, too, are no more personal, no more special, no more distinctive.

Greg Kearney suggests that all is not lost, noting the sale of most of Maine’s newspapers to a functioning non-profit, one of several in the nation where journalists have gathered to rebuild an industry hobbled and undermined by corporate ownership.

I won’t pretend to be neutral: I edited one of the tiny papers in that Maine bundle, and the non-profit was started by people I ran into in my Colorado days. And I’d add that we have a good non-profit here in New Hampshire, too.

I doubt many of these people smoke cigars, though I’ll bet a few of them cuss.

And I hope they like editorial cartoons.

Comments 14

Comments are closed.