Books: Bushmiller, Brown, Burning

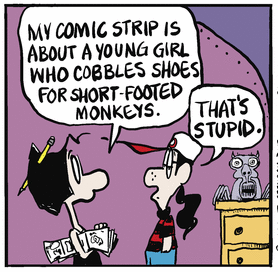

Skip to commentsBill Griffith’s Fancy for Nancy

Bill Griffith‘s graphic biography of Ernie Bushmiller Three Rocks will be released next month.

So it is a fine time for The New Yorker to review and preview the book and interview the author.

My first exposure to Nancy was in the funny pages of the Sunday newspaper delivered to my house in Brooklyn in the late nineteen-forties. I remember feeling drawn not to the art or the humor of the strips but to its lettering. Since I was just learning to read, “Nancy” seemed user-friendly. The letters were nice and big, with plenty of inviting airspace inside the word balloons, with a minimum of punctuation to decipher. So “Nancy” was imprinted on me at this time … It’s only later that I realized the zen quality of the strip.

At the end of the interview Bill talks about today’s Nancy:

Could you conceive of a Nancy who is relevant in 2023?

Actually, there is an updated version of Nancy out there, and it has its fans. The strip bears almost no relation to Bushmiller’s Nancy and Sluggo … I will resist making a judgment as to that decision.

So the answer is no—Nancy has no need to be relevant to 2023…

Digression.

Elsewhere is one not so shy about opining on Nancy post-Ernie.

At the risk of being hyperbolic, Ernie Bushmiller is the only authentic genius our nation has ever produced. Miles Davis, Mark Twain and Ernest Hemingway are garbage compared to the man who made Nancy.

Bushmiller is a hero in the Facebook comic strip groups that I belong to. The same is true of Olivia Jaimes, the genius who took over Nancy and elevated it to giddy new heights.

But Nathan Rabin’s Happy Place is not so happy when talking about a cartoonist between those two.

Back to books – the Scott Brown book.

Scott Brown was born to draw.

He sold his first cartoon when he was 10. When Brown was 14, he fell into a quarry, shattering his right elbow.

He didn’t let that stop him. Brown taught himself to be ambidextrous.

The Mechanicsburg native, who later became a Mansfield fixture, grew up to be a national cartoonist. Brown’s work appeared in The Saturday Evening Post, The New Yorker and Colliers, among many others, from the 1930s to the 1970s.

Another cartoonist biography, Scott Brown: Cartoonist by the cartoonist’s grandson, is out now.

“By early 1930, he came back without a penny,” Kuntz said of his grandfather. “He found that the soda shop was his place. A lot of people over 65, 70 years old in Richland County remember him.”

Brown worked at the soda shop by day and drew cartoons at night. Most of his income came from cartoons.

From the December 20, 1948 issue of Time magazine:

Manners and Morals

In Binghamton, N.Y., Students of St. Patrick’s parochial school collected 2,000 objectionable comic books in a house-to-house canvass, burned them in the school yard.

via Comic Book Legal Defense Fund

Some Americans have long been frightened of words and images, whether considered blasphemous (i.e., sacrilegious), pornographic (i.e., sexually suggestive) or subversive (i.e., threat to government). On October 17, 1650, the General Court of the Massachusetts Bay Colony condemned a 158-page theological book, Meritorious Price of Our Redemption, by William Pynchon, a merchant and founder of Springfield, MA, because it questioned the Puritan doctrine of atonement. The book was banned from the colonies and all copies publicly burned in the Boston marketplace.

Three centuries later during the 20th century, two issues galvanized the call for censorship — the popularity of comic books and the rise of juvenile delinquency.

Comments

Comments are closed.