CSotD: It’s American History Month

Skip to comments

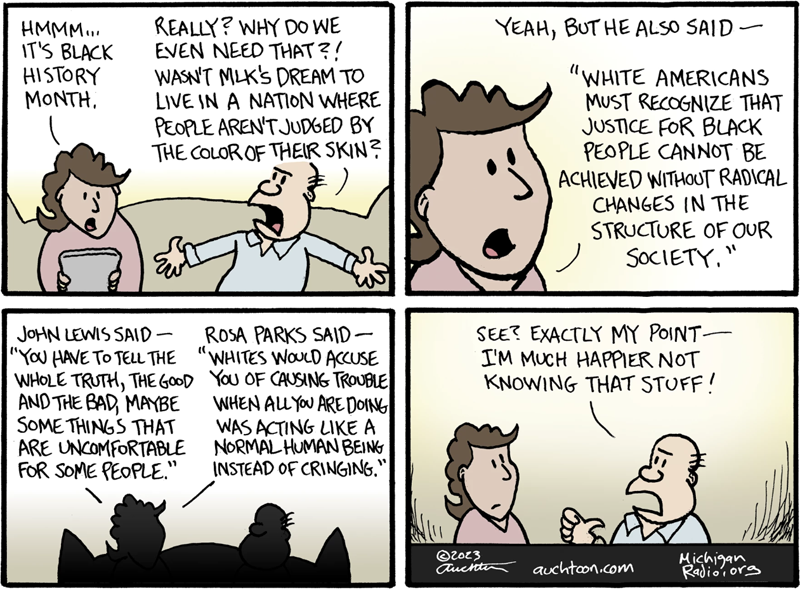

John Auchter frames our ongoing debate, a conversation that could have ended long ago: Why do we need Black History Month?

This NPR article does a good job of tracing the commemoration itself, including answering the question of why it is in February: The founder of the concept chose the month that contains the birthdays of Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass, with an additional twist of irony being that Douglass, having been born in slavery, did not know his actual birth date and chose Valentines Day as close enough.

Well, as they say in Ireland, “Near enough is close enough,” and, by the way, the Irish potato famine is required to be taught in New York Schools, as is the Holocaust, which puts the lie to any idea that Black History Month is, well, an “uppity” concept.

People not only have a right to have their stories told, but students have a right to learn the real history of their nation. As noted here the other day, the story of America is not of “the virus that spread from Plymouth Rock.”

Black History is a crucial part of American History.

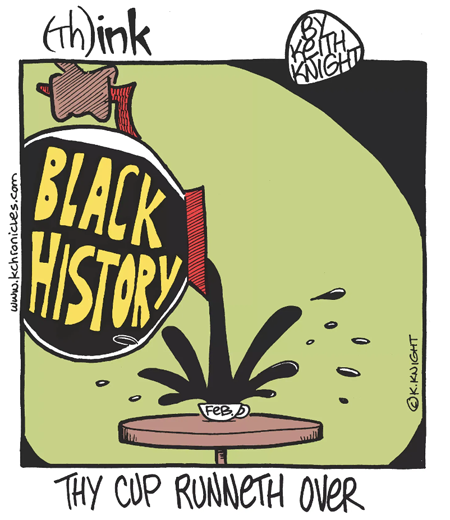

Keith Knight points out that there is a lot more Black History than will fit in our shortest month, and he’s right, particularly if you assume that Black History is, itself, a separate-but-equal category.

There isn’t time, within 28 days, to deal with everything that the African-American experience has brought to this nation. That’s not to say you can’t study it as a specialty, as you might study women’s history or any other subcategory within what is a massive overall topic.

When I was pursuing a masters in teaching (I got over it), we started with a history of education in America, which began with several lectures about the Transcontinental Railroad.

It left me scratching my head until we got past the Driving of the Golden Spike and the professor unrolled the developments that followed, including the centralization of industry along those railroad lines, and the rush to homestead the now-connected prairies to feed the immigrants we recruited to live in the urban slums and the need to get their little urchins off the street while their parents worked in the sweatshops.

Which gave reformers like Jacob Riis and Jane Addams the chance to fight the abysmal poverty and to use universal education as a tool in the search for a just society.

It wasn’t that America suddenly decided to become conscientious and decent, but if that was what it took to get those little street arabs under control and teach them to at least speak English ferchrissake, we were willing to finance the do-gooders.

The point being that all the things that came from the driving of the Golden Spike, huge as they were, are utterly dwarfed by the ultimate impact on our national story of those African captives who landed on our shores in 1619.

Juxtaposition of the Day

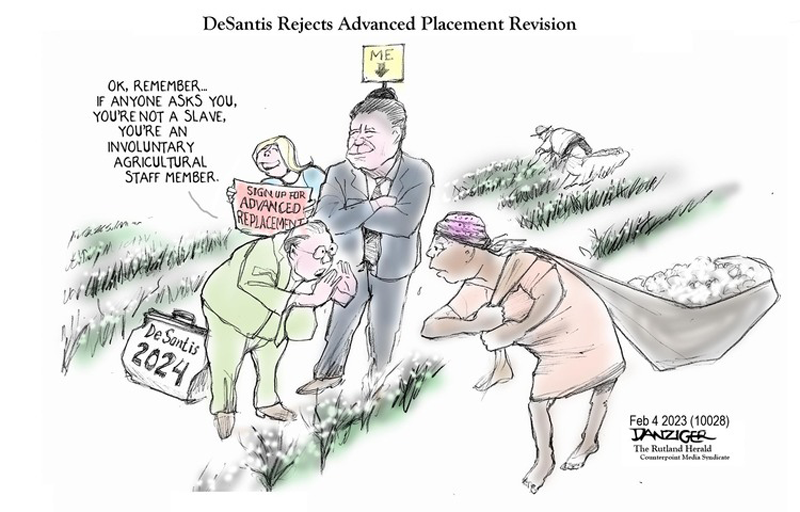

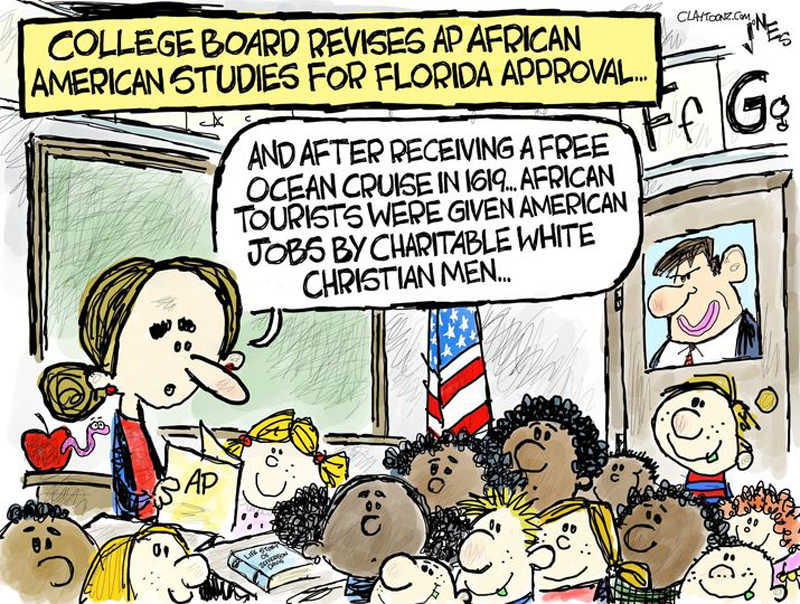

(Jeff Danziger — Counterpoint)

It’s not easy to shoehorn the Black experience into traditional Plymouth Rock based history, and the anxiety faced by that fellow in John Auchter’s cartoon is mirrored in the real world by the efforts of Ron De Santis and others to reject any effort to add more people to a predetermined mix.

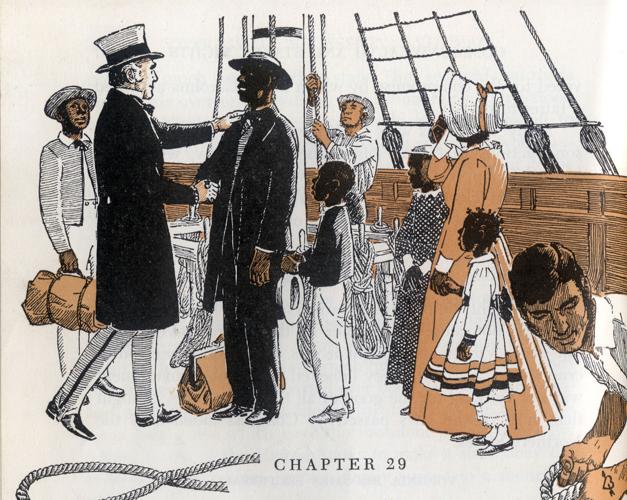

Both cartoonists face the challenge of exaggerating the coverups beyond what Virginia really did teach in its schools until recently, an astonishing set of lies that included middleclass Africans in western dress arriving on our shores, eager for good jobs.

Jones mocks those lies; Danziger winks to the audience by slipping in the part about it being involuntary.

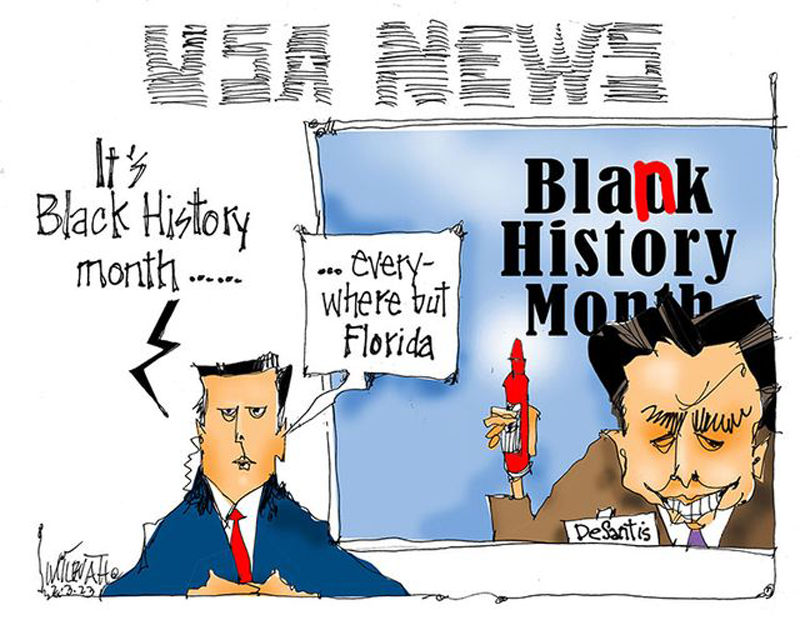

Deb Milbrath is more straightforward, accusing De Santis of negating Black history in Florida, which may also be an exaggeration, since, while his administration is forbidding discussions of gender issues, they have not actually told schools not to teach Black history.

They’ve simply insisted on letting the Ministry of Truth dictate what books can address racial issues, making it a felony to allow students to read unauthorized materials.

You may teach anything you like, as long as the Politburo in Tallahassee likes it, too.

But let’s go back to that Golden Spike, because the cure for bad history is not more bad history.

When I was in school, we were required to know that George Westinghouse had invented the air brake.

Now, first of all, his invention was not what allowed the building of the Transcontinental Railroad, the Golden Spike having been driven four years before the air brake was patented.

Moreover, the name of the inventor is about a thousand times less significant than the ultimate impact of that railroad, and we were wasting brain cells by memorizing his name instead of learning about the immigration and development that followed, including a fair amount of American Indian History, which opens a whole other conversation.

The Great Man School of History is part of our flawed approach to the topic, and the cure is not to make children also learn that Elijah McCoy, an African-American, invented a way to lubricate railroad wheels but to abandon the entire approach and teach, instead, the Great Movement School.

That doesn’t mean abandoning important people. It means choosing carefully the people at the heads of those great movements, people like Frederick Douglass and Susan B. Anthony.

And as you reform the curriculum, “choosing carefully” means that, if you’re going to add something or someone, you have to decide who or what is coming out. You can’t just keep piling on new things and expecting kids to learn it all.

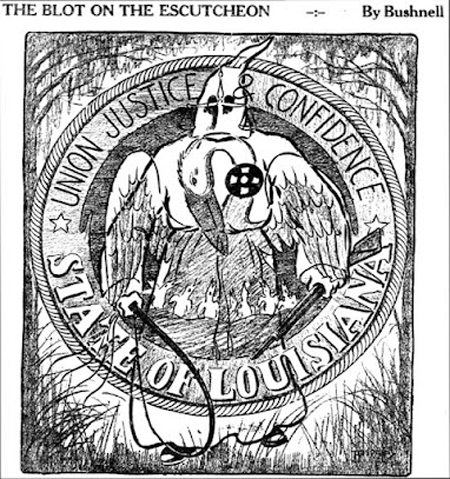

It’s also important to add perspective to those major movements and events. Paul Berge has posted a series of political cartoons about the Klan resurgence in the 1920s, but teaching about this moment in history opens a whole panoply of interlocking factors, of which the Klan is only one piece.

I was pleased to find mention in this NPR article about the Chicago race riots of 1919 of a factor I had previously stumbled across in newspapers from that era:

Not only were lynchings getting far more publicity — and sparking more outrage — than in the past, but the rise in racist violence was linked to Black WWI veterans coming home from France, where they hadn’t been required to shuffle and keep their heads down.

The response from white racists was violent, not just in the Jim Crow South.

This year’s Black History Month theme is Resistance, appropriately, because suddenly the Black victims stopped rolling over. In Chicago, a group of veterans broke into an armory, seized guns and defended themselves.

That shift of attitude in turn sparked the Double V Movement in the next World War, which in turn sparked the Civil Rights Movement, which has now sparked a round of racists attempting to impose their own history on a nation to which it no longer applies.

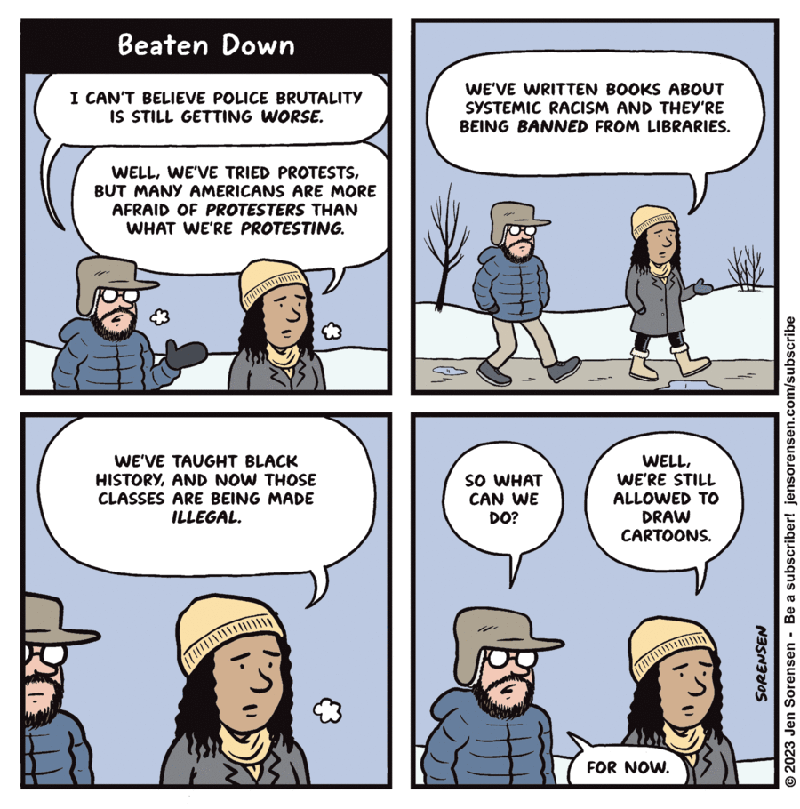

Jen Sorensen’s character may feel a bit of futility, but keep the faith, baby.

Keep the faith.

Comments 1

Comments are closed.