CSotD: Life, death, marriage etc.

Skip to comments

Stephen Collins reflects on the death of water cooler TV, a combination of too many things to watch, too many ways to watch and too many choices of when to watch. (Larger version here)

It comes hard on the heels of a whole lot of Festivus references, which reminds us of the days when we all shared catch-phrases Friday morning from the previous evening’s Seinfeld.

However, the Festivus thing sent me to the Seinfeld Wiki to find out when I had declared a jumping of the shark and quit watching the show.

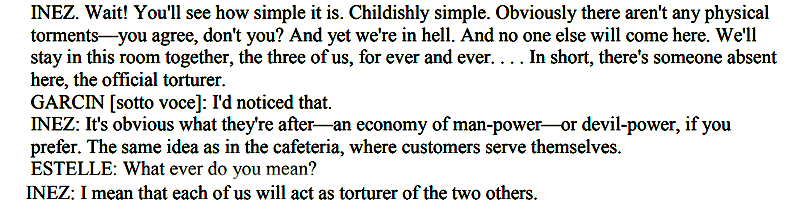

The answer is that, two seasons before the end, I realized the writers had gone from telling stories to simply coining catch-phrases for people to repeat in the office Friday morning, though I did tune in for the final episode, a take-off on Sartre’s No Exit, in which they were all killed in a plane crash and, after Final Judgment, sentenced to be confined to a cell together for their self-centered cruelty, in keeping with Sartre’s script:

Seinfeld aside, Collins is right that we no longer have that experience of chewing over a common video experience. Even if we can afford to subscribe to all the relevant streaming services, the odds of everyone having tuned in to the same thing are far smaller than in the past.

We are no longer a tribe, unified by telling shared folk tales around a fire. The electronic hearth is splintered beyond repair.

But going back to that final episode of Seinfeld, Crowden Satz offers a reflection that recalls the days of common memory, for those of us old enough to remember The Twilight Zone.

One of its classic episodes, A Nice Place to Visit, features a mobster who thinks he’s died and gone to heaven until he realizes that never losing at pool and always having the attention of a beautiful woman is, in fact, punishment, because risk was part of the joy of winning.

Satz takes things down to a more universal, and thus more chilling level, by going after the vain regrets of life, the unifying element here being that we can effectively put ourselves in Hell before we die by replaying those lost opportunities in our minds.

The good thing being that, like Ebenezer Scrooge, this is only a shade of what could be, and we have a chance to alter it, or at least to alter our interpretation of it.

As an example of that positive spin, it reminds me of reconnecting 30 years later with a woman I broke up with over circumstances, not because we wanted to. I’d often wondered “What if?” but found out she’d become a nurse, married a doctor who was a combination MD/DO, traveled to Africa and Tibet to study alternative medicine and then set up a practice with him, melding modern and traditional treatment.

I’d had a pretty interesting life in the interim as well, though nothing like hers, and I realized that, if we’d stuck together, I might have wound up like Joni Mitchell’s old boyfriend Richard, who “got married to a figure skater, and he bought her a dish washer and a coffee percolator, and he drinks at home now most nights with the TV on and all the house lights left up bright.”

Watching Seinfeld and collecting catch phrases to use the next day at work, while my wife nursed vain dreams of Africa.

Or maybe like the poor schlub in this Flying McCoys, AMS, seeking that unified experience not with shared TV shows but by telling strangers about his food and his family and his latest Wordle score.

Granted, I have a FB page where I do share personal things with a handful of personal friends, but I maintain another page with far more “friends” from the professional realm, who may not even know I have a dog.

Come to think of it, I somewhat divided things that way back when I used to go into an office for seven or eight hours every day. Some of us did, some of us didn’t.

To almost entirely change topics, I got a chuckle out of this Pardon My Planet (KFS), though I had to ponder his odd line before coming to the conclusion that he’s still married but just barely, and is certainly worth avoiding.

But it also made me think about the expression “confirmed bachelor,” because it’s a Victorian way of describing a gay man, back in the days when everyone knew but nobody much cared.

James Buchanan, for example, was a confirmed bachelor, and historians still speculate, now that we seem to think it matters.

In his day, there were snide remarks about the President and his great good friend and roommate Senator Rufus King, calling them “Aunt Nancy” and “Aunt Fancy,” but, in the end, not really fretting over it a whole lot.

In a slightly more modern time, George Bernard Shaw has Henry Higgins use the actual expression, describing himself and Col. Pickering in Pygmalion as “confirmed bachelors” more than once, as in this exchange:

That “straight question” is not a pun, BTW, but the rest is interesting because it obviously gave Lerner & Lowe the inspiration — and much of the opening dialogue — for “An Ordinary Man,” which they used to open their musical to the romantic possibility of his falling love with Eliza after all, which became even more pronounced in the movie than it had been in the musical.

Shaw was hardly so ambivalent, as a result of which his script was better, while his view of feminism as seen here and in other plays, allowed Hiller and Howard to rise far above the romantic approach Hepburn and Harrison were given to work with.

Euphemisms have their place, but so does realism.

Spoiler: She didn’t fetch his damned slippers.

Comments 1

Comments are closed.