CSotD: Living Document on Life Support

Skip to comments

I agree with Adam Zyglis that Second Amendment zealots are killing the “living document” of the Constitution.

I just wish they were the only ones involved in the crime.

As noted here before, the discussion of guns is not about guns but about politics, in which guns have become a measure of loyalty to competing visions. At each end of the spectrum is a zealot: “No restrictions” at the far right, “No guns” at the far left.

Some of it is simply pig-headed ignorance. I’ve also seen multiple claims that the Constitution only extended the franchise to white, landowning males.

There is no such clause. The Constitution left it to the states to set their standards for voters, and some did require that voters own land, for instance, but women were able to vote in several places for a few years, until local laws cut off that right, while African-American freemen were allowed to vote in some states while forbidden in others.

Anyway, unfairness was part of overall society, not an invention of the Framers.

Abigail Adams was right to ask her husband to include women’s rights in the Constitution and it’s a shame he dismissed her concerns. But you can’t lay the blame entirely on the Founders, given that we were still quarreling over the need for an Equal Rights Amendment in the 1970s, nearly two centuries after the Constitution was ratified.

(Quick Fact Check — Take this interactive quiz to see where women fared in 1970, compared to today.)

It takes some rummaging through the Federalist and Antifederalist Papers to ferret out the Founders’ intentions, but any relatively bright eighth grader can read the Constitution and get the basic facts straight.

To which I would add that basic civics should indicate that it’s called a “living document” because it was mainly based on principles, not specifics, and because it can be amended, and has been, often.

Benjamin Slyngstad, however, is just one of several cartoonists arguing that the Second Amendment was predicated on the technology of the Brown Bess musket.

As noted before, this would logically suggest that the First Amendment was predicated on the technology of hand-set type and presses that turned out one side of one page at a time, plus a distribution system that made most newspapers purely local.

I’d prefer to assume they meant “Freedom of the Press” as a principle, not a specific based on 18th century technology.

Similarly, their (soon to be discarded) belief in a citizen army had little to do with muskets, which certainly were wildly inaccurate, though an average soldier could get off three shots in a minute.

What the hunters had at home were rifles, which took a little longer to load but were highly accurate: One of Daniel Morgan’s riflemen picked off British General Simon Fraser at considerable range, swinging the Battle of Saratoga in the colonists’ favor.

The Framers expected to see hunting rifles, not army-issue muskets, at militia rallies, but — far more to the point — they certainly didn’t expect individual citizens to be showing up with cannons and mortars.

The Framers were not calling for citizens to own military-grade weapons and, as Kal Kallaugher (Counterpoint) points out, the AR-15 is not suitable for hunting anything but people.

Juxtaposition of the Day

And it’s a waste of time to quibble about muskets and AR-15s when the threat to this living document is in partisanship. If you think getting guns out of people’s hands is an impossible task, try getting money out of politics.

The Founders feared political parties, but infighting was an issue well before the first quill was dipped to write the Constitution.

In-fighting among partisan factions plagued the war effort during the Revolution. It drove Washington to distraction and was a major part of what motivated Benedict Arnold to try, instead, for a negotiated peace.

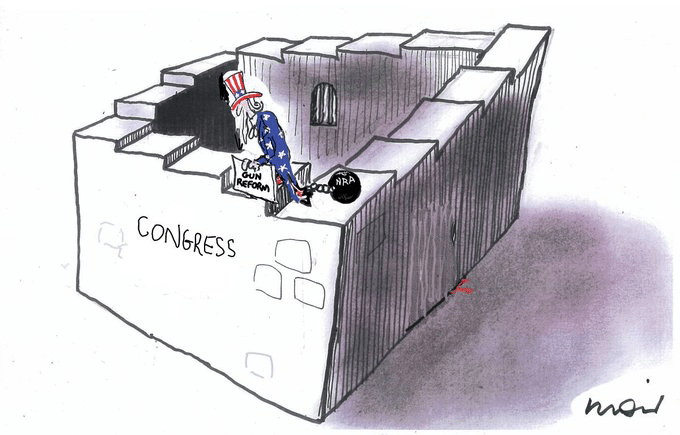

The fact that the Founders rejected a parliamentary system, in which the party with a majority in the legislature appoints the executive, is an indication of their anti-partisan intention, but, clearly, a case of a failed principle, because parties rose, and dominated the system anyway, powered, as Alcaraz and Moir both note, by financial contributions from outside interests.

The missing piece is that, in parliamentary systems, third parties are often the key to forming a majority government while, under our system, we’ve only had brief moments when they even drew attention, much less held any real sway, though a dozen independents in our Senate would certainly swing a heavy bat at the moment.

As it is, however, Bernie Sanders and Angus King do well to counterbalance Manchin and Sinema in the face of lockstep GOP solidarity.

While the real legislative power seems to be wielded by unelected people like Wayne LaPierre and Charles Koch.

Finally, however, Mike Luckovich points out that, while we debate and argue and do nothing, we’re condemning an entire generation of our children to live in fear.

There have been reminders that, while we mourn the kids killed in Uvalde and other shootings, others have survived and will carry both physical and emotional scars through life, but Luckovich goes beyond the impact on those physically present at these horrific events.

When I was little, I took the duck-and-cover drills at school seriously, but they remained highly theoretical. I’ve heard others of my generation say they were terrified that there would be an atomic war, but there had only been two atomic bombs dropped, a long distance away and years before we were born and in the midst of a war in which all sorts of terrible things happened to other people, but not to us.

By horrific contrast, when kids duck under their desks today, they do it knowing what has happened in schools just like theirs, and they do it in a world in which they see people brandishing semiautomatic weapons and bragging of their hostile, hateful attitudes, not just on TV but on the street, right next door and maybe at Thanksgiving dinner.

We can’t say to them “It can’t happen here” because it does happen here.

We can’t say “Don’t worry” because we worry ourselves, and we’d be damned fools not to.

And they’d be damned fools to believe us anyway.

Comments

Comments are closed.