CSotD: Anybody here remember print?

Skip to comments

(Some thoughts about newspapers, while I take Mother’s Day off to go visit the Aged P.)

Here’s the protagonist of an 1867 novel, “Ned Nevins, the News Boy, or, Street Life in Boston,” in which the plucky lad worked to rise above his grim surroundings, as plucky lads would in popular literature for the next half century or so.

Selling newspapers was a means of survival for homeless boys because newspapers were how news happened in those days.

The first regularly published newspaper in America was the Boston News-Letter in 1704, but by then papers had been around in Europe for a century.

News-Letter was an excellent title, because that’s essentially how the very first newspapers began: As summaries for shippers and merchants to track the comings and goings of their trade.

These first newsletters summarized who had arrived and who had left and what they had on board, but, naturally, they included reports from arriving ships. It was of interest to the business to know of storms they had encountered, ships they had hailed, changes in governments and of any wars and unrest in the various places they traded.

Once a ship went over the horizon in those days, you simply had to wait. If it seemed late, it might be disquieting to know of those storms or wars, but at least you had a clue of what might be happening. And good news might inspire you to invest in another venture.

This all made for interesting reading for people outside the trade, and fairly soon, the announcements of which merchants had fresh shipments of flour or cotton or other products for sale began to take the form of paid ads, and the newsletters began to cater to the general public.

Some were subsidized by the government or by the merchants, but advertising quickly emerged as the main support, with the retail sale of the paper itself being only a portion of their revenue, as newspapers grew from single sheets to multi-page publications with reader-oriented news, features and advertisements.

The invention of the telegraph in the 19th century meant faster reporting for small, local papers, as trains no longer brought in pre-set lead columns of “boilerplate” stories from the city.

By 1905, when Earnest Elmo Calkins published his milestone book, “Modern Advertising,” there was other media than newspapers, but it consisted mostly of magazines, billboards and street car placards.

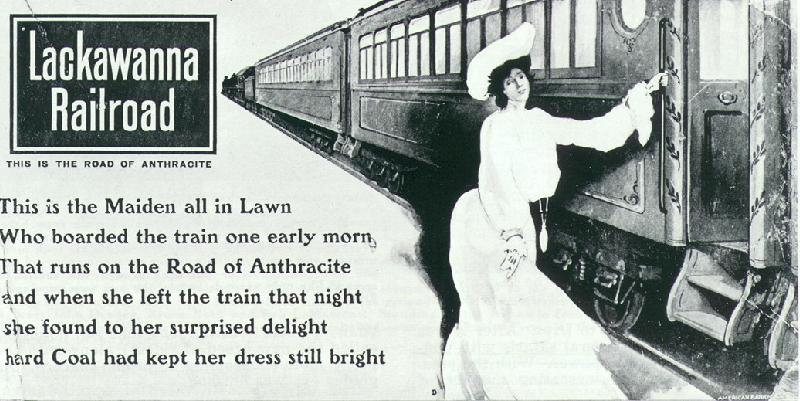

Calkins transformed this placard into the first ad campaign featuring a continuing character, Phoebe Snow, whose poems praised the Lackawanna Railroad for using hard, not soft, coal and thus providing a soot-free ride.

A quarter century later, this 1924 Dorman Smith cartoon captures the moment when radio went from a nerd hobby to a full-blown public medium.

While several nations did begin licensing radio sets in order to support the medium (and still do), the US took another approach.

A year, almost to the day, before that cartoon ran, RCA’s David Sarnoff had declared his opposition to taxing radio users.

Whether his concern was truly for the poor slum dwellers who deserved to hear symphonies or for the advertisers who would pay rates based on listenership is no real secret.

But he was tapping an existing level of interest, as shown by the two-page Boston Globe spread in which his remarks appeared, surrounded by how-to articles for aspiring radio bugs, and ads for both do-it-yourself gear and finished radio sets.

Radio took away some advertising from newspapers, but, like moving pictures, it generated interest, and advertising.

And speaking of motion pictures, this 1938 ad — admittedly for a blockbuster — was three columns wide and more than half the page tall. That’s good money.

Newspapers retained an important advantage over radio: Radio could tell about cigarettes and detergents and automobiles, but newspapers could show, and showing is more compelling.

But after the War, a more challenging competitor appeared on the scene, and, again, local papers capitalized on TV’s popularity.

My parents paid attention to those TV-inspired ads, though that’s my older brother and sister.

I was a few years younger. Davy was cooler than Hoppy anyway.

I don’t know about that show; it was on after my bedtime, but local TV was, at least for a time, as much an advertising partner as the local department store.

But the explosion of TV and its ability to show, not just tell, began to siphon away advertising from newspapers, particularly in the category of low-priced consumer products like cereal. Nationally purchased ads for cereal, coffee and similar products disappeared from papers.

For larger ticket items from tires to refrigerators the take was that television sparked the desire — a picture of a car couldn’t compete with a TV ad showing it cruising along — but that people then turned to the local newspaper ads for prices, sales and other specific, local details.

Even in that diminished food category, newspapers retained some power on the local level: You learned not to go grocery shopping the day the food inserts were in the paper, because people might recognize the product from TV, but the newspaper told of local discounts and offered coupons.

The parking lots and the aisles would be jammed.

For newspapers, these were still the Good Old Days.

Then two things happened, somewhat simultaneously.

(I’ve used this 1992 Jack Ohman cartoon so often that he finally sent me a color version to replace the B&W one I’d clipped from Editor & Publisher.)

One monumental change was a growth in acquisitions.

A lot of local papers had consolidated during or just after the war, the smaller paper in a two-paper town having been decimated by the loss of automobile and appliance advertising as those industries diverted production to the war effort, as well as by wartime rationing of paper and increased costs.

But Wall Street acquisitions towards the end of the 20th century were a different matter. In 1920, 92 percent of newspapers were independent. By 2000, that number was down to 23.4 percent, and falling.

The “local” newspaper stopped being local.

And if button-down corporate editors made newsrooms less fun and less flavored by go-with-the-gut coverage, a greater financial damage Wall Street owners wreaked was the installation of corporate publishers.

The old-school local publisher — often a co-owner of the paper — could be a crusty SOB to work for, and reporters despised having to pitch in on stories for the annual tabloid insert for his wife’s god damned flower show.

But the ads in that fat little special edition were payback for the free space he’d given his Rotary and Chamber pals over the year for their own shindigs. And they weren’t free.

That sort of off-the-cuff community symbiosis ended when Wall Street stepped in.

Today, a publisher who does well is quickly promoted and moved out. A publisher who doesn’t is just as quickly kicked to the curb.

As a result, the corporate publisher is a plug-and-play robot who, one way or the other, never sticks around long enough to get through the chairs to become president of anything influential, and, frankly, is lucky if the community’s business leaders could pick him, or her, out of a lineup at all.

Installing a faceless front-office drone in place of Good Old Ralph or Betty made selling local ads a much greater challenge.

And then this happened. As with radio a half century earlier, computers began as a geek hobby and the papers jumped aboard with feature stories capitalizing on the fad.

But it wasn’t a fad, and, as it grew and spread, the newsroom continued to cover it with an enthusiasm that wasn’t shared in the circulation department, where it was felt that reporting on the topic was one thing, but having reporters gushing about the new media and peppering their stories with hipster phrases like “dead trees” seemed disloyal at best and suicidal at worst.

A bigger problem was that, while radio had come to eat our lunch, the Internet wanted to gobble down dinner and breakfast, too, and we didn’t have Good Old Ralph or Betty to frame a quick, effective response.

We had to propose solutions to Corporate, which responded with instructions to wait while they held some meetings and pondered some ideas and worked out a group-wide policy.

And so we sat and did nothing while Craig’s List ran away with a huge chunk of local revenue, and showed the Realtors and car dealers an opportunity to save money, too. Advertising income fell by 40 percent.

It was bad enough that Corporate diddled while our revenues burned, but there was no way to compete with Craig’s List anyway.

Unlike as it had been with radio or television, this wasn’t a competition. He wasn’t taking the money; he was simply giving away what newspapers had been selling.

There were ways to keep going, if you were permitted to do so, but those distant committees forbade local response and offered nothing to replace it except assurances that all was well and that they had great plans and that everything was under control.

For example, I was working at a paper in the first part of this century that began a successful e-edition program, attracting a growing number of paying customers for an on-line replica.

We were ordered by corporate to close it down and make everything free.

And we were simultaneously ordered to increase our paid circ, which is what we thought we had been doing.

The illogic of their empty bromides and one-size-fits-none policies was absolutely maddening.

You can tell, f’rinstance, that this Elderberries is fictional, because a real call would be coming from an outsourced phone bank in the Philippines.

We not only stopped serving local readers, we stopped employing them.

Ah, well. I’m far over my usual length now, and I’ve still got a pile of marketing horror stories that would double it.

Never mind. My late friend Richard Thompson summed it up several years ago.

Ted Rall was less diplomatic, but no less accurate.

And Pearls Before Swine made it a little more humorous but was no more optimistic.

Today, major metros have been downsized from doorstops to pamphlets, and their staffs have been equally devastated, on orders from distant beancounters with cookie-cutter policies to emphasize next quarter numbers over long-term investment.

There is some cause for moderate hope, however.

You don’t have to like Jeff Bezos to like the resources and loose leash he’s given the Washington Post, and perhaps he’s touched off a bit of a trend.

An attempt by a wealthy entrepreneur to purchase, and rescue, some papers from the Tribune chain seems to have fallen apart, but, on a more micro scale, three small Vermont papers were just purchased by a regional entrepreneur who seems interested in local journalism, according to a story in one of those papers.

I strongly believe local papers could work, if they were local.

If they were responsive.

If they were part of the community.

After all, if we can have artisanal ice cream shops and artisanal bakeries, we can have artisanal newspapers.

Ned Nevins and Jimmy Brown are ready to get back to work any time.

Comments 5

Comments are closed.