Cartoonews – Editorial (Now and Then)

Skip to comments

The jury, composed of the members of World Press Freedom Canada, met on April 13 to select the winners of the 21th World Press Freedom International Editorial Cartoon Competition.

© Anne Derenne

Bado’s blog showcases the winners and honorable mentions.

We all had our heroes when we were young. Some of mine were Johnny Unitas, Ted Williams, Randolph Scott, Fred O. Seibel, and Bill Mauldin. If you are not familiar with the last two, read on.

© respective copyright owners

Fred and Bill are both gone, Fred in 1968 and Bill in 2003.

Columnist William Rowell remembers Fred O. Seibel and Bill Mauldin.

In my career, I have angered a lot of people. It’s not that I regret it, but I do question myself as a professional when someone I didn’t want to piss off gets angry. When it comes to those I did want to anger and I make them drool with rage, I don’t care.

© Pedro X. Molina

In the world of journalism, cartoonist Pedro Molina (Estelí, 1976) is known for being elusive when it comes to interviews. He prefers not to be photographed and, unless necessary, does not appear in videos. He describes himself as a person who does not talk much, but that depends on the subject.

When asked about his work, his creative process, and the role of his profession in the face of power, Molina doesn’t stop talking. He feels comfortable discussing the subject and reflecting on the introspection he has gone through to refine his humorous criticism in the course of his career.

Confidencial interviews Pedro Molina.

From less than auspicious beginnings, Henry Jackson (H. J.) Lewis found a way to make a living as an artist. Along the way, he became the first African American political cartoonist whose biting criticism of racial injustice ruffled more than a few feathers.

From the Arkansas Democrat Gazette is a profile of Henry Jackson Lewis.

More at Commonplace and at the H. J. Lewis homepage.

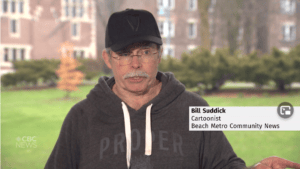

The Beach Metro (Toronto) Community News just began its 50th year, and the team is celebrating with stories and interviews featuring long-time contributors, columnists and volunteers.

© Bill Suddick

Bill Suddick remembers his time as Beach News cartoonist.

Religious leaders have long feared irreverent drawings that could challenge their authority. We should remember that amid the latest effort to prevent the use of Muhammad cartoons, says Bob Forder.

There is nothing new about cartoons being used as a device to poke fun at the religious. They have been a contentious source of blasphemy prosecutions and allegations ever since technical developments enabled their mass print production.

Bob Forder and the National Secular Society look at 19th Century cartoons about religion.

Comments 2

Comments are closed.