CSotD: Monumental Questions

Skip to comments

Bob Moran and I appear to be on opposite sides of the “tearing down statues” issue, but his commentary opens the question to a potentially fruitful discussion.

The matter is more complicated in Britain not simply because they have more history to process but because, over here, we’ve focused on a relatively straight-forward false-history concocted in the 1920s as “the Lost Cause” was being promoted.

Hence this three-pronged

Juxtaposition of the Day

The differences among them are more than nuance.

Wuerker comments not on history but on current events, and I agree that we seem to be at a tipping point, similar to that recent moment when there was a sudden, almost spontaneous agreement that same-sex marriage was nobody else’s business and it became legal.

He may be a little optimistic, but I don’t think he’s wrong: The mass of people have awoken to the injustice of how African-Americans have been treated by the police.

Bell takes something of a more long-range view, which salutes the struggle rather than celebrating the (hopeful) end result. Again, he’s not talking history or he might have shifted the voting panel to the first position, since the registration drives that were part of the Civil Rights Movement helped elect black mayors and governors, which in turn helped (eventually) turn the tide.

But in summing up the immediate moment, he’s correct that involvement on several levels has been necessary to bring about the change in hearts and in the landscape.

And, finally, Fitzsimmons offers an almost plaintive hope for the future, suggesting that the attitude shift will be enough to push this hateful vision into the past.

While it seems naively optimistic, I don’t think it’s unreasonable. The voices speaking up include not just the usual political hellraisers and a few Hollywood liberals, but, for example, both sports figures who normally keep out of politics and the leagues that want them to do just that.

However, while there is only tepid support for retaining the names of Confederate generals on military bases, the howls of outrage — like Michael Ramirez‘s — over HBO’s decision to add a disclaimer to “Gone With The Wind,” indicate that we haven’t turned the corner.

The pushback on GWTW is instructive, first of all in a general condescending manner whereby we nobly grant Those Others a right to somethingsomething, as long as our own lives are not changed by it.

A conceptual cousin of Phil Ochs’ lyric, “I love Puerto Ricans and negroes, as long as they don’t move next door,” and not much of a step up from doing away with segregation but maintaining the right to keep country clubs the way that makes members comfortable.

So let’s have another

Juxtaposition of the Day

Whether it’s adding footnotes to movies or dumping statues, rethinking history always makes somebody uncomfortable, and so it needs to be done thoughtfully.

The statue of Columbus in St. Paul was torn down by protesters the other day, while a statue of Boy Scout Founder Baden-Powell is slated for at least temporary removal in Dorset, England.

It’s a pairing that requires some knowledge of specific history and, on a more general level, of the complexity of history.

The complexity issue is that we tend to view historical figures within a single moment or a single aspect of their lives, but, of course, real people aren’t that one-dimensional.

So it’s easy to view Bill Bramhall‘s poke at army camps named for traitors with a laugh, because Arnold has come down in history as the archetypal traitor.

But Arnold’s story is far more complex: He was a true hero who was badly treated by the Continental Congress and, unlike John “Live Free or Die, Boys” Stark, who would simply stomp off back to New Hampshire when he was tired of the abuse, Arnold did, indeed, plot to betray his erstwhile allies.

Those who appreciated the conundrum honored his heroism at Saratoga, where he basically saved the day and thereby the nation, with a battleground monument not to the man but to the leg in which he was badly wounded.

By sharp contrast, almost nothing we’ve learned about Columbus is true, since he was the subject of a fictionalized biography by Washington Irving and then put forth as a “hero” to honor Catholics in general and Italians in particular.

Which, if he had simply sailed over and reported back, wouldn’t matter, but his treatment of the natives is not simply regrettable but horrific, and not simply in retrospect but as noted at the time.

Defending a statue of Columbus because he was a great explorer is like defending a statue of John Wayne Gacy because he dressed as a clown and performed at children’s hospitals.

Baden-Powell is a more troublesome character: He is remembered for founding the Boy Scouts, which brings its own baggage but has been a significant social group for a lot of young boys.

But Baden-Powell himself was reportedly fond of watching young boys skinny-dip, and while there’s no documentation to prove he was an active pederast, it’s a troublesome coupling with the problems the group has had.

Plus he was a racist and a Nazi sympathizer, but then so were Henry Ford and Charles Lindbergh and what are you gonna do?

I’m glad you asked.

The answer is to stop teaching Great Man History and switch to Major Moment History.

The coming of Europeans to the New World was a Major Moment, and it’s more important to study what it meant to everyone — everyone — involved than to memorize the names of individuals in the big chairs.

Important Point: The cure for Great Man History is not adding the names of Great Women and Great Minorities to the list of meaningless crap kids have to memorize.

It’s teaching how Major Moments — inventions and immigrations and wars and pandemics and economic booms and busts — changed normal lives and, hence, the flavor and tone of the entire nation.

It means fewer statues and more local museums.

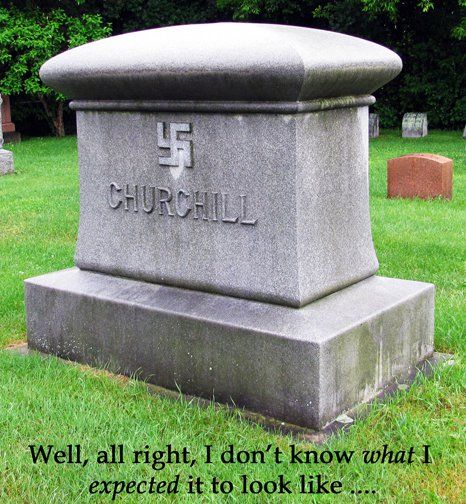

(Oh, relax. It’s not him.)

Comments 6

Comments are closed.