CSotD: Protecting “our” right not to know

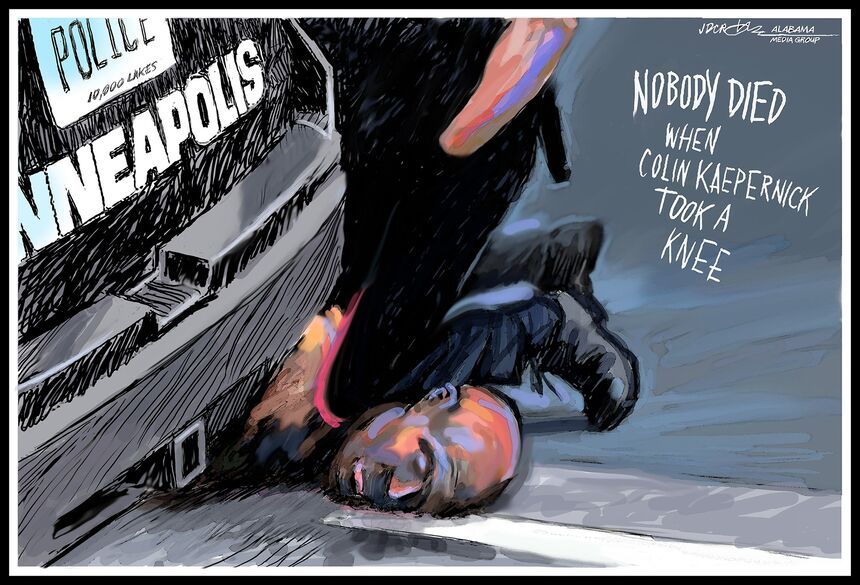

Skip to commentsI’m giving JD Crowe top billing because less is more and he kept it plain, but managed to sweep in what happened and why it matters.

He didn’t swap in the Statue of Liberty or the Statue of Justice or otherwise adorn a scene that speaks for itself, nor did he ask an obvious rhetorical question about Colin Kaepernick’s demonstration against police brutality.

It’s easy to bring a lot of baggage to this incident — we’ve got a lot of baggage stored up — but that mostly winds up with finger-pointing and fault-finding and nit-picking and excuse-making.

F’rinstance, the Mayor of Minneapolis moved quickly, first to suspend and then to fire the officers involved, but, hours later, the streets still erupted in protest. WTF?

Well, TF turns out to be that the Mayor isn’t the police chief or, apparently, the whole city council, and that there has been a simmering resentment between the black community and the Minneapolis police that shouldn’t have gotten to this point.

JD simply points out that, while people bitched and moaned over Kaepernick’s protest, here’s why that protest matters.

Minneapolis has to deal with their situation, and apparently they have to deal with more than what happened that day in that place.

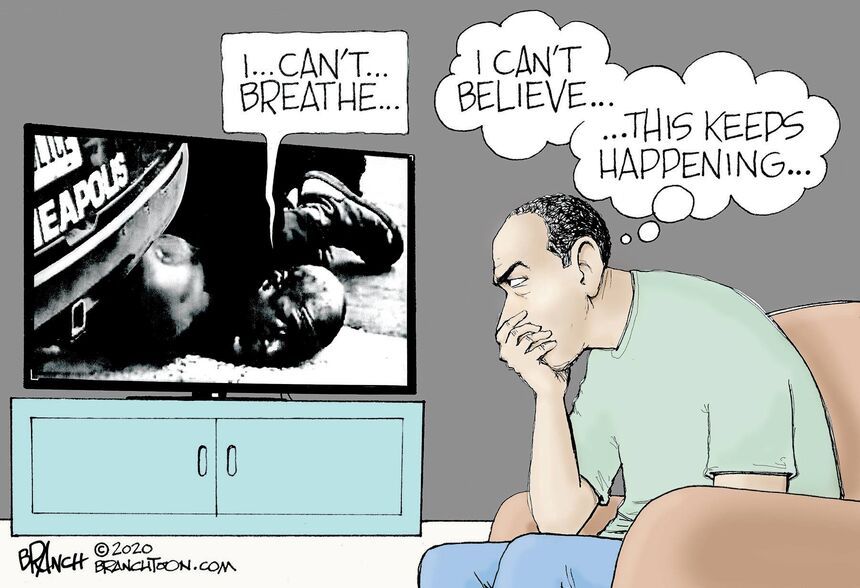

John Branch puts forth the more sweeping question: How long, Lord, how long?

If you want to play the Black History game, you can go back to Reconstruction to find lynchings, and, in those days before broadcasting, when most news was local news, maybe “we” didn’t know. (“We” being a toxic word with its own racist overtone.)

Then black GIs returning from France a century ago had seen what the world beyond Jim Crow was like, and they walked a little taller and were lynched for it, and it made the papers and “we” shook our heads.

And if Emmett Till were alive today, he’d be 79, but he’s not.

And “we” shook our heads, again, 65 years ago.

Having long hair in the wrong towns and cities a half century ago was an interesting lesson, because we were the ones being randomly harassed by the police, though I only knew one case that resulted in murder.

But we learned, or should have, by being stopped and questioned for no reason, and by being bullied by the police, including being beaten.

Had a friend thrown in with convicted felons because of his long hair. He was beaten, sodomized and had his jaw broken.

And four months before the Chicago Convention, a police riot devastated a peaceful anti-war demonstration, and I remember the “good cops” begging us to stay back while their brethren cracked heads in the plaza by the Picasso.

As we left the area, a car full of young black men drove past, waving fists out the window and shouting “Now you know! Now you know!”

As soon as I cut my hair short, of course, I was safe.

But if I go through Chicago and see those checkerboard hat bands on the police, my stomach still tightens up.

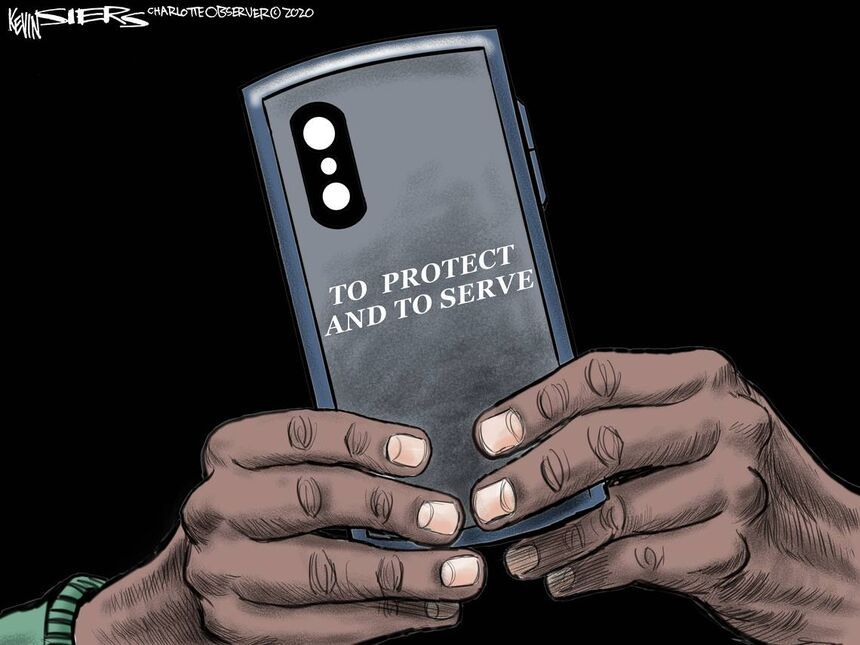

It makes me particularly love Kevin Siers’ cartoon, because the only way anyone knew what happened to us was that it was near noon in the center of town on a workday.

One of my friends was rescued by some visiting Kansas City businessmen who took him up to their hotel room and got him medical treatment for bruises and a broken collar bone. Outraged letters began to appear in the Chicago papers.

But how often do you get that many witnesses?

Siers is right: The cellphone has become the best defense against the “we” who don’t want to know.

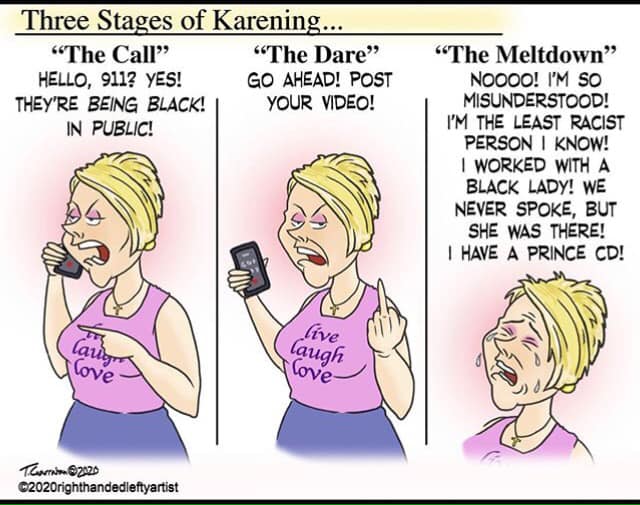

I wish people hadn’t seized on “Karen,” because I’ve known some very nice people with that name, but I like Tom Garahan‘s explanation of how “we” protect our right not to know.

And if it’s not that nice lady in Central Park who phoned in a fake police report, it’s that Concerned Citizen in, of all places, Minneapolis, who wanted police to come arrest some men for felonious blackness, but who has since explained that he doesn’t have a racist bone in his body.

Unless you count his thumbs.

Ike, Jack and Lyndon don’t live here anymore

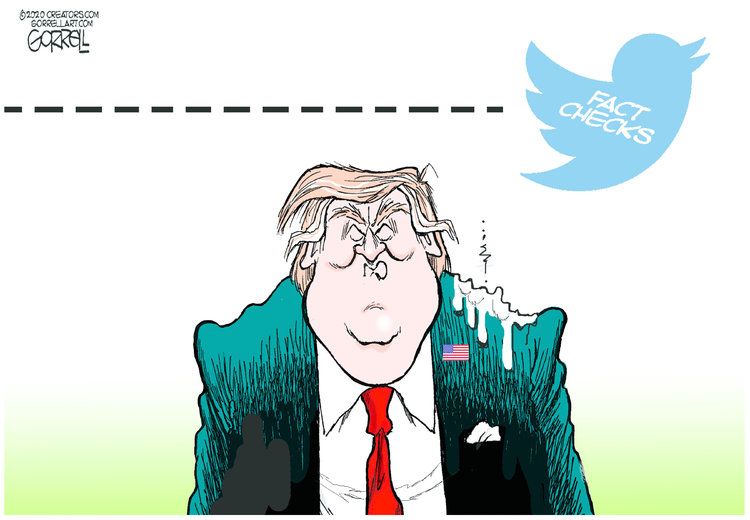

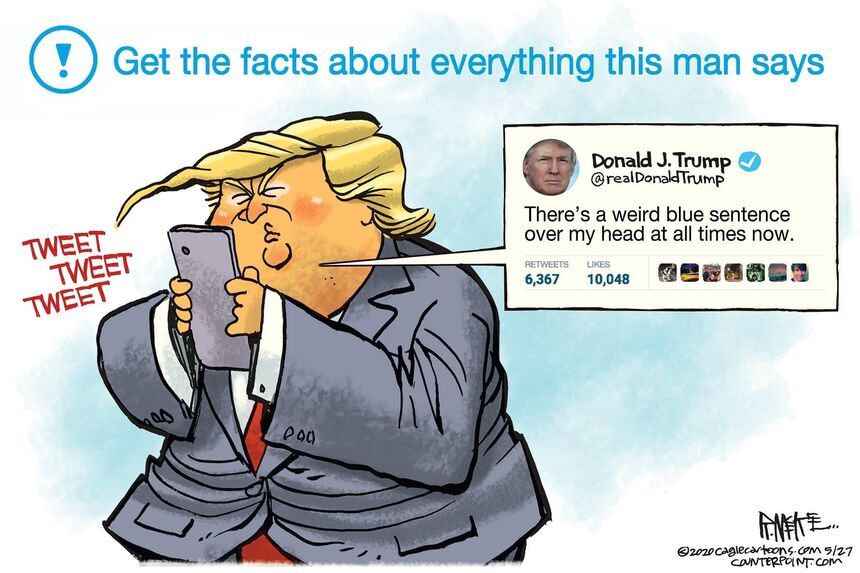

Used to be that, when violent prejudice struck, they’d call in the feds to straighten things out. Today, as Bob Gorrell points out, we need to call in Twitter just to keep the president’s tongue from making that weird fork shape.

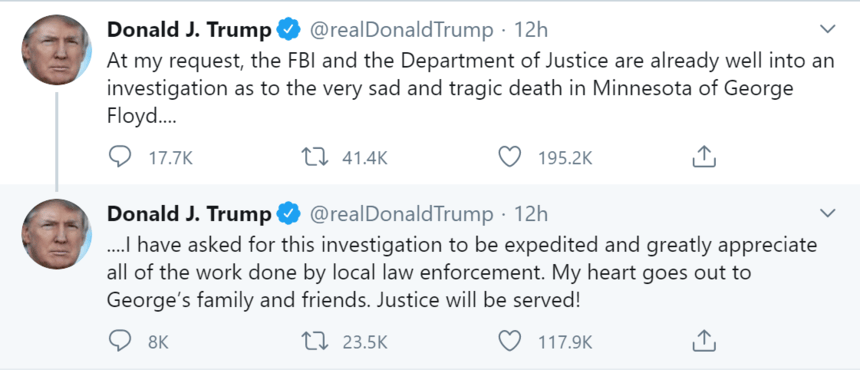

He did express dismay at what happened in Minneapolis and promised to call in the FBI, who had already been called in, and who he has repeatedly, publicly declared untrustworthy.

And the Dept of Justice, which will investigate until they find something, at which point, if recent history is any indication, AG Barr will call them off.

When Louis Renault said, “Round up the usual suspects,” his deliberate inaction proclaimed his patriotism and credibility in the fight against the Nazis.

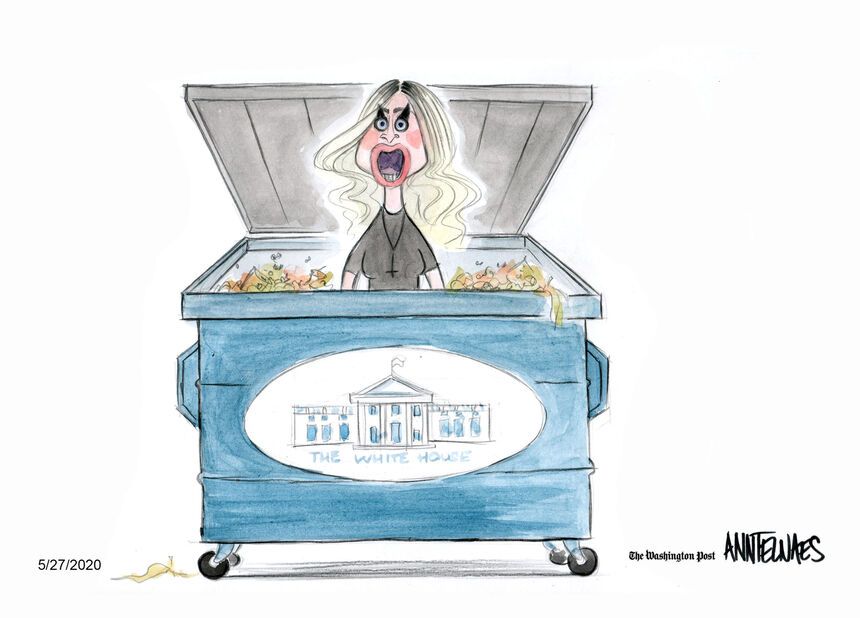

It doesn’t have the same ring coming from this crowd, in which Dear Leader’s Official White House Spokesmodel — seen here through the lens of Ann Telnaes — declares that vote-by-mail is rife with fraud.

Though she’s voted by mail 10 times in 11 years, and her boss has also repeatedly voted by mail.

However, the fact that something has been done by Trump and members of his staff does not mean it is not fraudulent and corrupt.

In any case, McEnany explained that her boss “is against the Democrat plan to politicize the coronavirus and expand mass mail-in voting without a reason, which has a high propensity for voter fraud.”

The coronavirus being, in fact, an excellent reason for expanding mail-in voting.

What she means, however, is that “we” can be trusted with mail-in ballots, because “we” aren’t … “them.”

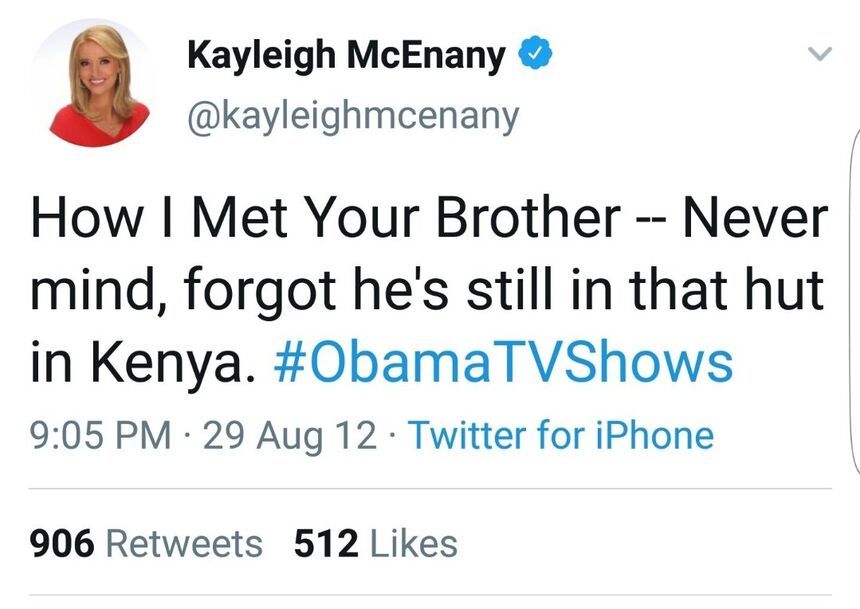

“Them” being, for instance …

… people from Kenya and other shithole countries.

Not the nice places “we” come from.

And if Bob Gorrell isn’t conservative enough for you, here’s a similar caution, more plainly stated, by Rick McKee, who is rarely mistaken for Abbie Hoffman.

While the final word on “we” — though one can hope — goes to Big Bill Broonzy:

Comments 3

Comments are closed.