Comic Strip of the Day: Storm Warnings

Skip to commentsNormally, a hurricane is a disaster not only for those it impacts, but for editorial cartooning as well: It’s one of those events, like the death of a celebrity or, for that matter, a kerfuffle at a tennis match, which makes everyone pick up their pens and say nothing.

However, these are not normal times, and Clay Bennett suggests the overlap of disasters as well as the overlap of priorities.

And let me pause here to say that I’m a couple of chapters into “Fear” and the main advantage of this book over “Fire and Fury” is Woodward’s reputation and his penchant for detail, though Wolff seems a more fluent writer.

“Fear” begins with a gracious preface in which Woodward credits his long-time assistant, Evelyn Duffy, for her organizational skills, which is no small thing on a book in which documentation is not only massive but critical.

However, he doesn’t owe much to his book editors, though I suppose we don’t know what they started out with, stylistically.

What they ended up with is a book that shows signs of quick editing on deadline. For instance, there’s no excuse for a graf like this:

“Manafort’s place was beautiful. Kathleen Manafort, his wife, an attorney who was in her 60s but looked to Bannon like she was in her 40s, was wearing white and lounging like Joan Collins, the actress from the show Dynasty.”

First of all, it’s a pedestrian over-loaded garbage truck to begin with. I understand the relevance of establishing that Manafort was a man of expensive and refined taste, and with a wife cut from the same cloth. And I realize that trying to recreate the experience of a source rather than something you’ve observed first-hand is hard.

But, goddammit, if nothing else, either your readers know who Joan Collins is or you drop the simile. Don’t slow things down even more to explain it.

Well, he’s not Ernest Hemingway, and he’s not even Ernie Pyle, either, but I suppose that’s just a lot of literary insiderness.

It doesn’t diminish the importance of the book but it does diminish the pleasure of reading it. With a normal schedule and a compliant author, these bumps and clanks would have been smoothed out in the process of going from manuscript to finished product.

And it’s not like the response to the book is going to come from anybody with literature in mind, as this Dwane Powell commentary should remind us.

The courtly days of Daniel Patrick Moynihan are long past, but it’s more than that: Lyndon Johnson was viewed by his colleagues as a barbarian on a personal level, but he was both feared and respected as a barbarian who knew the game and didn’t mind getting his hands bloody playing it.

Congress was his tool, not the opposite, and, if he slipped the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution past them, he also crammed the Civil Rights Act down their unwilling throats.

Andy Marlette notes one result of the current game, in which, according to Woodward, a determined, doctrinaire GOP majority allies itself with a feckless play-actor who thought you could pay off the national debt by printing more money.

Gary Cohn has denied that “Fear” reflects his experience, but he hasn’t, to my knowledge, otherwise explained the mounting deficit, and, if you’re going to deny eating the cake, you should wipe the frosting off your face.

Meanwhile, the play-actor continues to boast of economic triumphs that 30 seconds on Google will disprove.

And it seems I’ve drifted off from my initial discussion of Hurricane Florence and cartooning, but I was merely setting the stage.

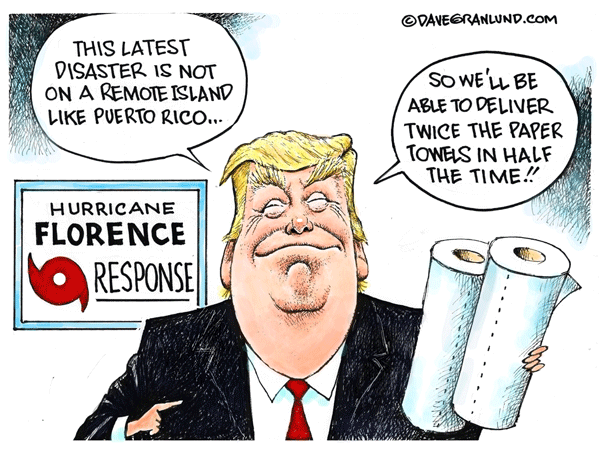

Dave Granlund isn’t the only cartoonist to make jokes based on the infamous paper-towel tossing, and he plays upon an actual Trump statement, though there’s little triumph in finding a time when our self-centered, self-promoting Dear Leader said something foolish.

As Nick Anderson suggests, there’s plenty of “fool me once/fool me twice” to go around, not only in disaster preparedness but across the board.

However, his cartoon contains more than a bit of wishful thinking. There are certainly people who feel this way, but how many? And how much influence can their horrified skepticism have?

Well, how much influence has it had so far?

To go back to Clay Bennett’s opening salvo, there’s a critical question over what it would take, not for the hopelessly enthralled Deplorables, but for the Silent Majority, to wake up and pay attention to Bob Woodward, Michael Wolff, the anonymous insider from the Op-Ed page, and the evidence plainly in front of them.

So far, they seem content to continue to believe what they want to believe and to ignore what they want to ignore.

I admire the dark humor in David Fitzsimmons‘ grim take, which contrasts Trump’s insensitive, self-centered bragging with the tragic reality of the deaths which, if he didn’t cause them, he has not only failed to acknowledge but seems determined to ignore.

And Marlette appropriately shifts the blame from our ineffective leader to the nation that has, so far, aided and abetted this heartless masquerade.

I like Kal Kallaugher‘s take, which provides a nice bookend to Bennett’s opening, but if it were only a case of shameless, OJ-level denial in the Oval Office, we’d be back in Watergate territory.

Half a century ago, when only the White House was in pieces, Congress stepped in and the American people felt that the system had worked.

Today, we’re mired in a disaster in which over half the Congress and a generous portion of the rest of us are — actively or passively — playing along.

As I write this, Florence appears to be diminishing, and, though far from harmless, seems unlikely to provide us with the horror show that might trigger an awakening.

I’m glad lives may be spared, but, heartless as it seems, a massive disaster just before the mid-terms might have turned the famous question against an entire nation:

At long last, have we left no sense of decency?

Comments

Comments are closed.