CSotD: The Actually Files

Skip to comments

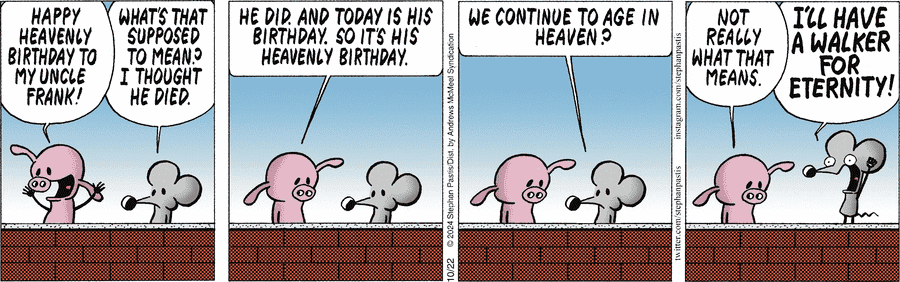

Pearls Before Swine (AMS) indulges in some theological speculation. It’s inappropriate to tell other people how to mourn, and while there is a point at which it becomes obsessive, that point is different for everyone.

Still, Rat has a point and I can’t think of a source that suggests we age in heaven, while, although I think there are different schools of thought about whether tattoos follow us there, it’s actually well established that, if you lose a limb here, it will be restored in heaven.

Though there’s not much theology behind all the wings and harps and haloes and clouds. I prefer the visions of the afterlife in either Here Comes Mr. Jordan or Heaven Can Wait, the latter being an extremely successful remake and update of the former, proving something about the afterlife or Death being not proud and there always being room for improvement and redemption.

Or something.

For my part, I’m agnostic. I have no idea what happens next and I’m actually in no hurry to find out.

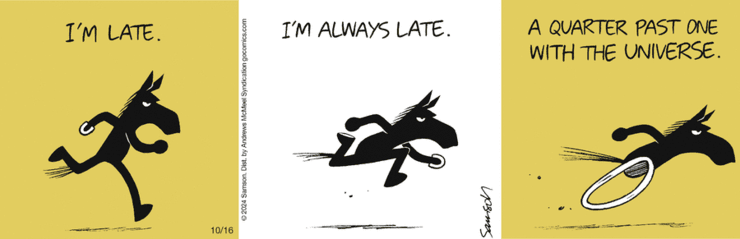

I’m hoping to be one with the universe, or perhaps, like Darkside of the Horse (AMS), a quarter past, but, again, I refuse to hurry.

Meanwhile, F Minus (AMS) explores the other end of the theological scale, wherein you assume that there must be some practical explanation for things you don’t understand, and, since you know you’re not stupid, that it’s some mysterious, cosmic explanation.

The joke here is applying it to our own minor failures, when, actually, it’s based on a racist assumption that people with limited technology are incapable idiots.

It assumes some technically advanced master race must have helped those bumbling morons, and since it’s unscientific to assume it was angels, it must have been little green men.

Which is, actually, just as silly.

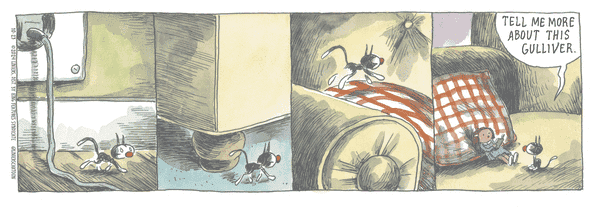

Actually, while Lemuel Gulliver’s first journey was to the land of Lilliput where things are tiny, as seen in this Macanudo (KFS), he also went to Brobdingnag, where everything is enormous.

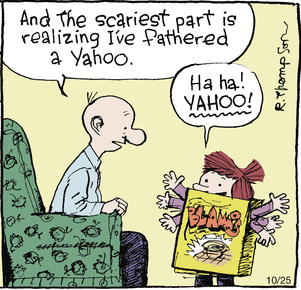

He also went to the land of Houyhnhnms, a society of kindly, wise horses who kept stupid, violent, vulgar human-like farm animals known as Yahoos, hence the term.

He also visited a bunch of philosophical lands so bothersome that we mostly skipped over them in my college seminar.

Outside of college students, however, nobody has actually read past the Lilliput part, so they assume it’s a children’s story, perhaps ignoring the fact that Gulliver was exiled from the country for putting out a fire in the Queen’s palace with a stream that would have made Arnold Palmer jealous.

BTW, Arnold Palmer’s daughter says he actually thought Donald Trump was, well, a putz.

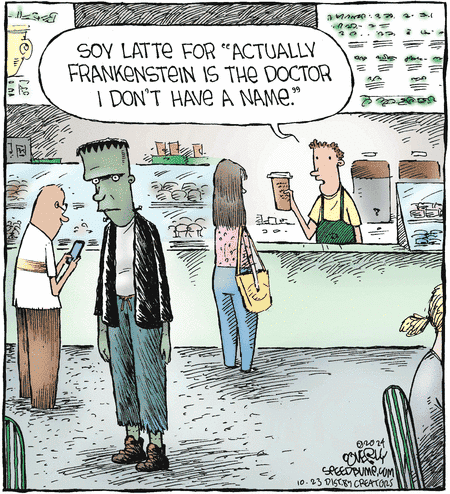

I love Speed Bump (Creators), but, actually, while nobody called him by name in the novel, he suggested one which attached to him in various adaptations:

Oh, Frankenstein, be not equitable to every other and trample upon me alone, to whom thy justice, and even thy clemency and affection, is most due. Remember that I am thy creature; I ought to be thy Adam, but I am rather the fallen angel, whom thou drivest from joy for no misdeed.

I think he’d have told the barista “Adam” even if he couldn’t produce an ID. Lord knows Starbucks can’t be fussy about who buys their overpriced coffee these days.

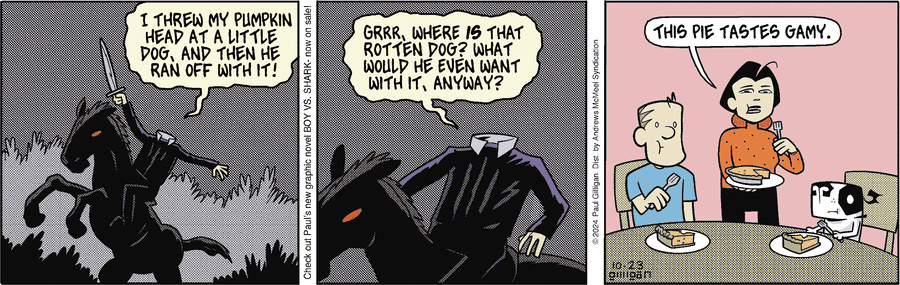

I also like Pooch Cafe (AMS), but, actually, there was no Headless Horseman, only a jealous bully.

We read the story in seventh grade English, learning that Katerina Van Tassell wore “a provokingly short petticoat, to display the prettiest foot and ankle in the country round.” Mrs. Jarvis explained that, in those days, showing your ankle was actually considered sexy.

We didn’t have to be told that Ichabod Crane was something of a nitwit or that Brom Bones was a big jerk, since the story made that clear.

But while Disney made the Headless Horseman seem very real and his head a flaming jack-o’-lantern, Washington Irving was actually a great deal less specific about what happened that night:

Brom Bones, too, who, shortly after his rival’s disappearance conducted the blooming Katrina in triumph to the altar, was observed to look exceedingly knowing whenever the story of Ichabod was related, and always burst into a hearty laugh at the mention of the pumpkin; which led some to suspect that he knew more about the matter than he chose to tell.

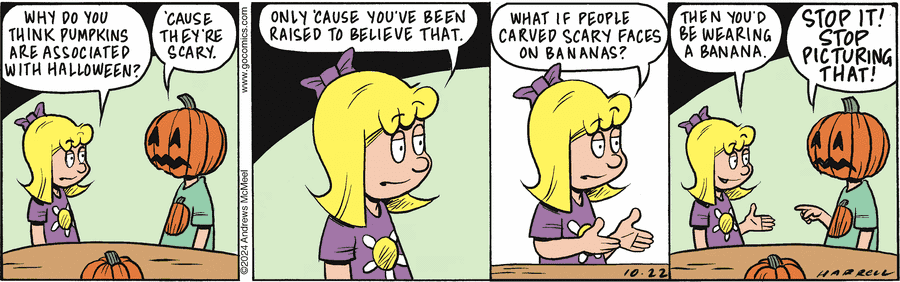

Katy is quite correct in Adam@Home (AMS), and the adoption of pumpkins is actually a New World innovation.

The Celts originally used turnips or rutabagas, switching to pumpkins after coming to America, pumpkins having been unknown in Europe.

Which is another argument against Brom Bones carving the pumpkin he hurled at Ichabod Crane: The Celtic tradition hadn’t likely caught on yet in the 18th century Dutch community whence the old story originated.

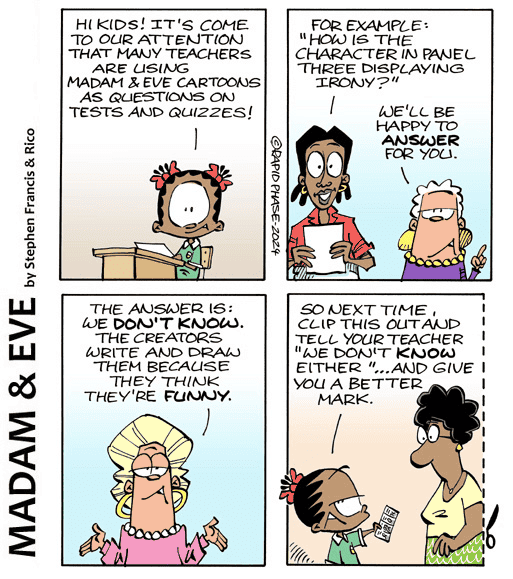

Madam & Eve brings up a more complex Actually.

I infuriated a professor with a paper positing that Ulysses was not a great novel because it wasn’t a novel, except in the sense that the Statue of Liberty is a building, with a door, a staircase and, in the crown, windows.

I said Ulysses bore the attributes of a novel but actually contained so many riddles and intentional symbols that it was hardly limited to that definition.

Joyce purposefully larded that book — and the Wake — with symbols, which made them different from normal literature in which, as the cartoon argues, symbols are in the minds of literature teachers.

Sort of.

Authors may not insert them intentionally, but, as the Irish say of fairyfolk, “I don’t believe in them, but they’re there.”

It’s actually a sort of Rorschach Test administered subconsciously between creator and consumer.

Example: In a short story, I had a high school senior come home, shower, change and start out to his car, only to be interrupted by his mother tapping on the picture window. She asked when he was coming home, he answered, both mouthing their words rather than shouting.

Somebody said they liked the symbolism of them being so close, yet having to struggle to communicate. I just meant he was in a hurry to go see his girlfriend.

But I suppose subconsciously yeah, I guess, whatever.

Like the fairyfolk, the symbols are there, but you needn’t believe in them.

Unless you want to.

Comments 7

Comments are closed.