Wayback Whensday – Way, Way Back

Skip to commentsThe Creation of the Comic Strip as an Audiovisual Stage in the New York Journal 1896-1900

Eike Exner, for Image Text, explores the origins of “sound” in late 19th Century comics of The New York Journal.

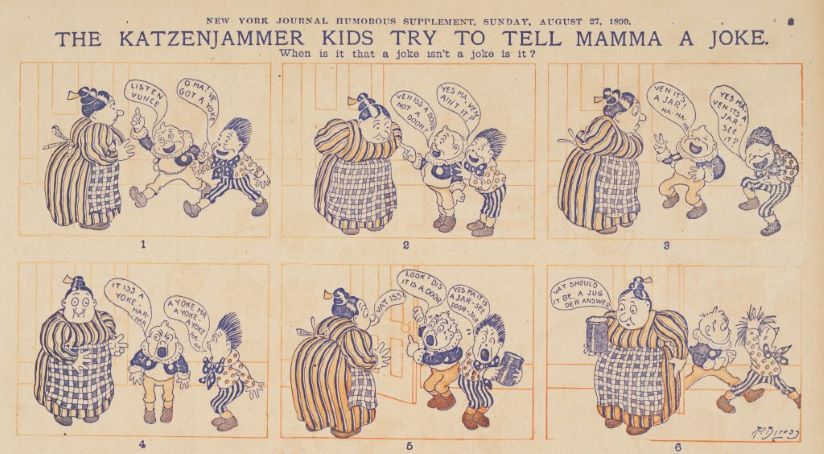

Some histories of comics imply that the form started by Outcault was immediately continued by Rudolph Dirks, whose Katzenjammer Kids made their first appearance on December 12, 1897, a month before the Yellow Kid (as signed by Outcault) last appeared on January 23, 1898 (if not counting the May 1 cameo). Often this link is supported with an image of Dirks’s March 27, 1898 Yellow Kid parody featuring the Katzenjammer Kids (and a dog with a balloon), implying that the Katzenjammer Kids simply took over where the Yellow Kid left off. The actual Katzenjammer Kids

franchise, however, did not feature its first speech balloon until a year later, on March 19, 1899, and did so only in a rare single-panel cartoon. The separate seven-panel Katzenjammer Kids strip above it stayed silent. It wasn’t until July 2, 1899 that Dirks first used a (single) speech balloon in a “Katzies” strip, though this strip also featured other dialog written underneath a panel. The first Katzenjammer Kids

to use speech balloons and not use external dialog was published the following month, a single panel cartoon on August 6 and a multi-panel strip on August 20, 1899. On August 27, the first strip appeared in which characters actually talk and respond to each other using balloons, when the Kids tell Mamma Katzenjammer a joke (“Ven iss a door not a door? Ven it’s a jar!”) and try to explain it to her, albeit in vain (the strip ends with the Kids leaving in frustration while Mamma contemplates a container the Kids pointed to in their attempt, wondering, “Vat should it be, a jug der answer?”). This episode of the Katzenjammer Kids is the earliest work I have found that can claim to make use of a truly audiovisual stage and hence be an example of the modern comic strip form beyond all doubt.

A quite interesting and full exploration of the allusion of sound in print comics.

**********

Lost Literacies Strips Down the Dawn of Comics

Most people consider the introduction of the Funny Pages in the late nineteenth century as the birthday of the “modern” American comic strip. Alex Beringer is not most people.

A literary historian and professor of English at the University of Montevallo, Beringer dates the history of comics earlier, to roughly the mid-1800s, a period of prolific and uninhibited experimentation. He came to this understanding by piecing together the medium’s fractured archaeological record, diving through myriad online resources and archives. In the middle of the nineteenth century, New York-based artists followed the lead of their French and Swiss colleagues, particularly Rodolphe Töpffer, the “Father of the Comic Strip,” exchanging single-image political cartoons and caricatures for multi-panel sequences that, many believe, for the first time enabled them to play around with characterization, worldbuilding, and—well—storytelling.

Coming decades before the standardization of speech bubbles and panel borders, these early American comics seem to have little in common with their modern, more streamlined counterparts; they featured sudden and purposefully jarring jump cuts reminiscent of the yet-to-be-invented film montage or musical notes instead of text. One comic artist tells a story through shadows behind the curtains of a window; another, with hieroglyphs the reader must decipher with the help of a legend.

“The audience for this first wave of US comic strips was strikingly sophisticated in its reception of this material,” Beringer writes in Lost Literacies: Experiments in the Nineteenth-Century US Comic Strip [link added], which chronicles this oft-forgotten renaissance.

In his new book, literary historian Alex Beringer demonstrates how the birth of the genre of printed comic long preceded the Sunday Funny Pages.

Tim Brinkhof, for JSTOR, interviews Alex Beringer about his book exploring very early U.S. comics.

**********

Opper, Outcault and Company

The 10 page article below appeared in the June 1905 edition of Everybody’s Magazine. Written by the American journalist and humorist Roy McCardell, the article is subtitled “The Comic Supplement and the Men who Make It”. By 1905, as the article points out, the Sunday newspaper supplement featuring comic strips was ten years old. McCardell’s piece takes and inside-baseball look at the state of the Sunday comics, providing anecdotes and rumors about the major newspaper cartoonists and syndicate folks of the day.

As you’ll see by the images on the website’s homepage and within the article below, there were some wonderful drawings created specifically for this piece. Interestingly, even though the magazine published a superb self-caricature by Gus Dirks, he is not even mentioned in McCardell’s article. Maybe the stigma of Dirks’ suicide made it difficult to talk about him in a public forum. Sadly, it was a missed opportunity to get some contemporary views on Dirks’ wonderful work.

Comments

Comments are closed.