CSotD: D-Day w/ Only One Wheelchair

Skip to comments

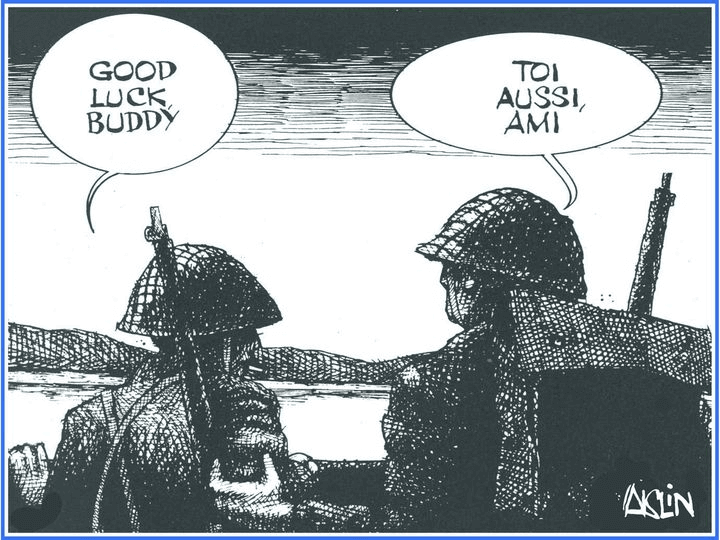

Aislin starts off our D-Day commemoration in part because the Canadians tend to get bunched in with the British forces in other commentaries I’ve seen, but mostly because he marks the day by remembering strong, young men while most others are depicting old guys in wheelchairs, sometimes saluting.

Saluting happens in cartoons on military holidays: It’s the graphic equivalent of “Thank you for your service.”

As for wheelchairs, it matters that we’re just about out of WWII veterans, but that seems more like a reason to bring back the memories than to depict the end of the road.

My father enlisted too late to be involved in D-Day, though he’d caught up with his unit in time to be at Dachau, which was not a barrel of laughs either. However, while over there he visited Dieppe where the Canadians attempted a landing in 1942.

Looking over the lay of the land, he said it was surprising that any of them made it at all.

Tough times. My mother says they were told not to ask returning veterans about their experiences, but to let them talk about it if they wanted to. My dad had a number of self-deprecating, humorous stories to tell, but he never brought up the other stuff.

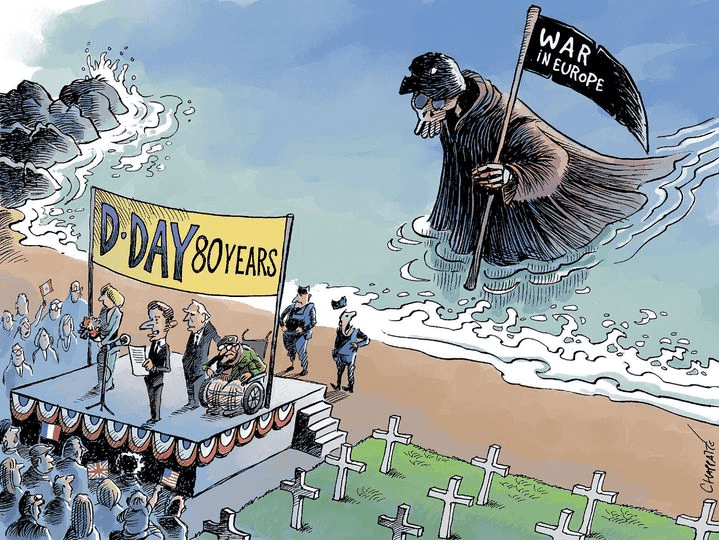

I’m giving Patrick Chappatte an indulgence allowing a wheelchair because he’s using it to illustrate not that we’ve forgotten the veterans but that we’ve forgotten the lesson, while the crosses remind us that not everyone involved in the invasion ever got to be in a wheelchair.

And that holding commemorations is certainly secondary to maintaining vigilance.

I was surprised to see so many cartoons referencing D-Day on June 6, 1944 itself, including this Dorman Smith piece. It’s important to remember that we had a great many more afternoon papers then, which gave time for more in-depth coverage, though the time difference with France meant that even the morning papers had the story.

But while the invasion itself was top secret, the fact that it was coming was clear enough that, by June 7, local companies had full-page ads celebrating the event and reminding people to buy War Bonds. I’m sure that people in Binghamton knew Fowler, Dick & Walker, but note that the store makes very little pitch for itself beyond a note pointing out that they have a bond sales booth on the main floor.

A factor that often gets lost in our second-hand remembrance of the war is that while D-Day was the largest assault upon the Axis’s European holdings, they’d already suffered a major defeat in North Africa, as seen in this Farsi cartoon.

The key battle of El Alamein was in the fall of 1942, a year and a half before the Normandy Invasion.

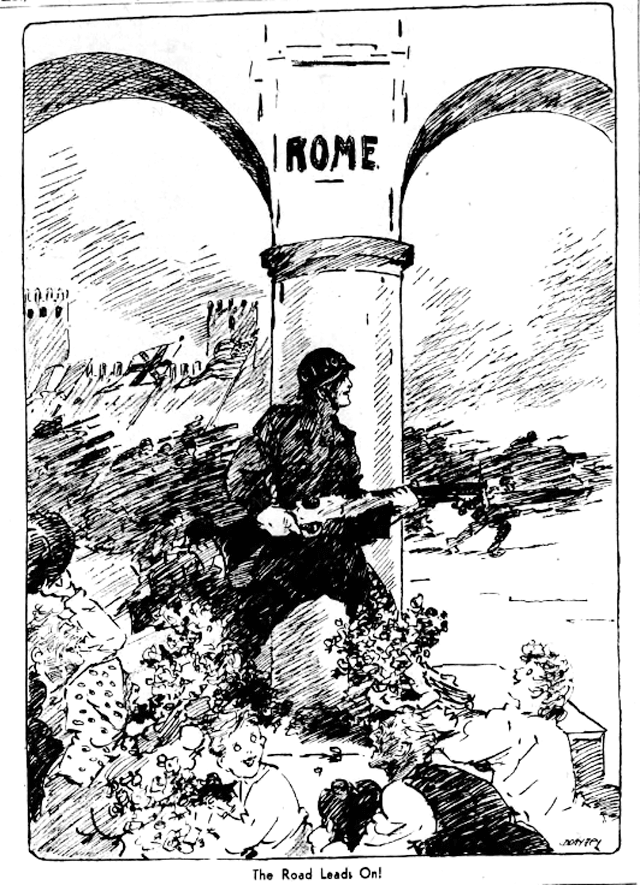

As James Harrison (Hal) Donahey recorded in the Cleveland Plain Dealer, Rome fell to the Allies two days before D-Day. It wasn’t the end of the war in Italy, but it followed a very tough campaign, commemorated in Catch-22 and cartooned at the time by Bill Mauldin.

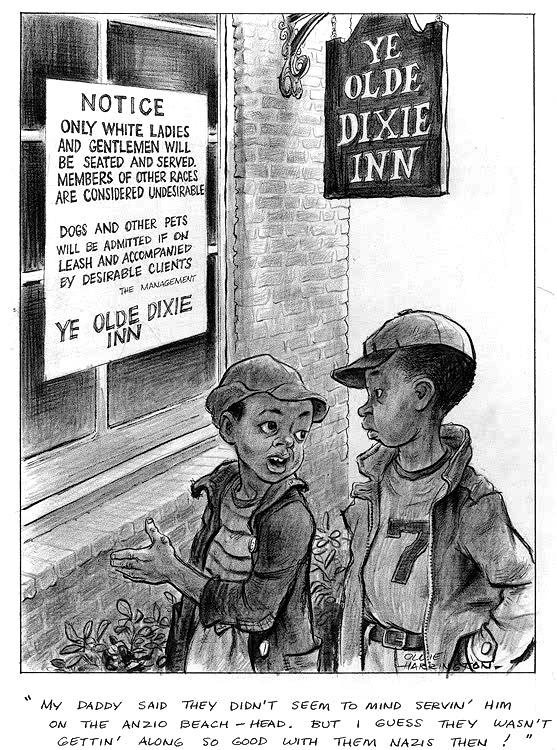

And remembered by Ollie Harrington in 1960, at a time when Black veterans were fed up with having been forgotten.

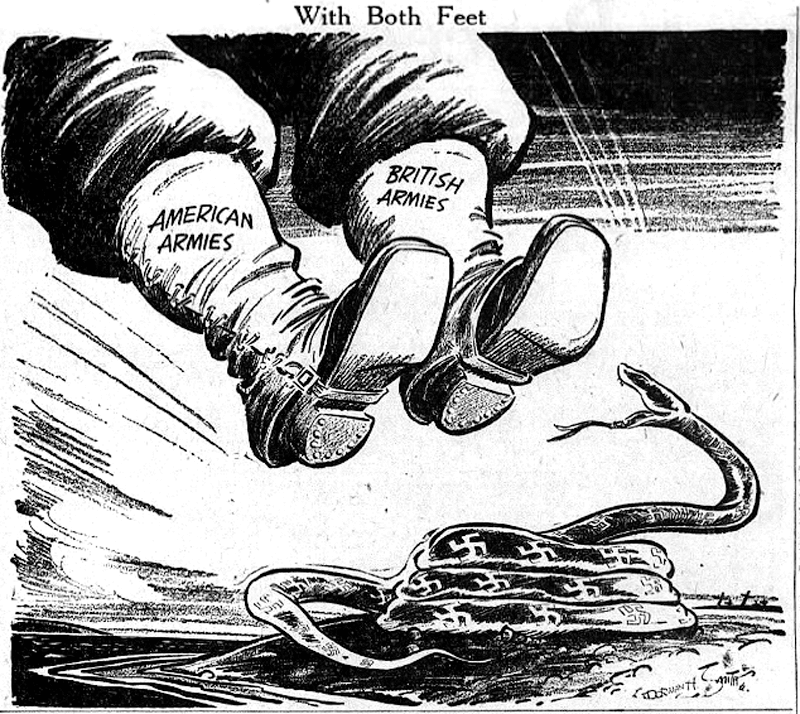

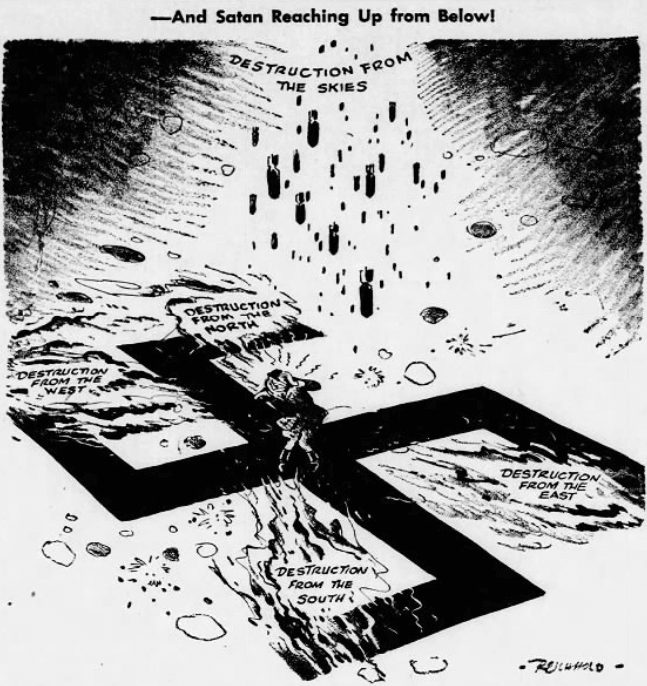

As Ralph Reichhold illustrated in the Pittsburgh Press, Hitler had plenty to fret over by June 6. The Normandy Invasions were a major development in the war, but it shouldn’t be forgotten that the Russians were making things hot on the Eastern Front as well.

Plus this: I made some remark about the war when I was about 12 and my mother pointed out, “You have to remember that, at the time, we didn’t know who was going to win.”

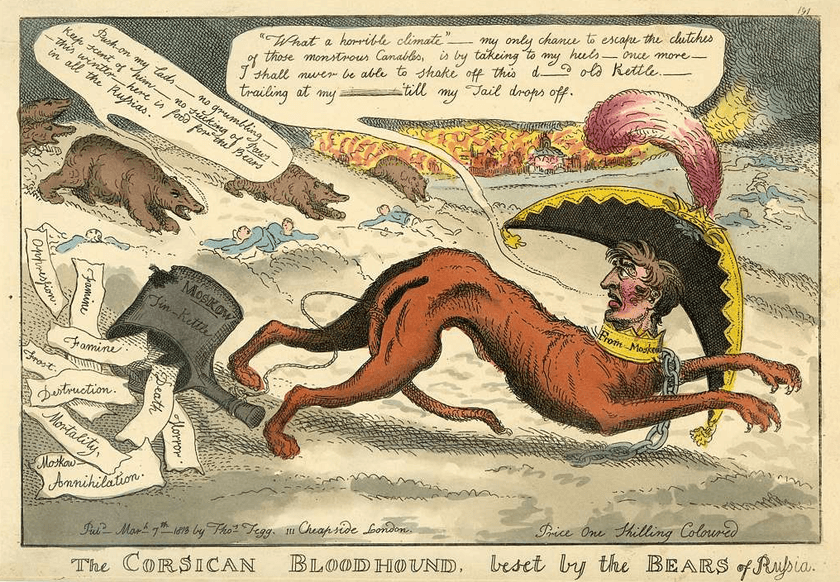

Which causes me to switch wars and feature this Thomas Tegg cartoon, drawn after the outcome of Napoleon’s 1812 invasion of Russia had become clear.

I’ve just come in my re-reading of War and Peace to the period after the Battle of Borodino, a Russian victory similar to the one of which Pyrrhus famously said, “If we are victorious in one more battle with the Romans, we shall be utterly ruined.”

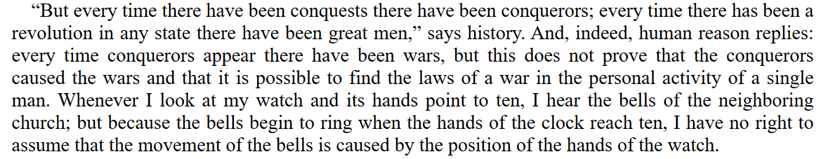

Tolstoy criticizes historians, citing Zeno’s Paradox of a race between Achilles and a tortoise, in which Achilles can never win, because he must always get halfway between himself and the tortoise, who, however slowly, keeps adding to the necessary distance.

It’s only a paradox, Tolstoy says, if you look at things as specific moments rather than within a realistic ongoing flow.

Historians, he writes, look at the moment and pontificate about what Kutuzov should have done, but they assume, first of all, that he knew exactly everything that was going on, when sending out a number of observers resulted in his getting that number of conflicting reports.

Kutuzov also had to see that the wounded were taken to safety and that troops were re-supplied with both ammunition and food.

And while that was going on, Napoleon was contemplating the same ongoing flow of issues, and still had a larger force than the Russians.

When we look at a moment in history, Tolstoy says, it’s like looking at a moment in the race between Achilles and the tortoise. Not only is it unfair to the real people who had to deal with the complete flow of events rather than a dubious snapshot of perhaps a misleading moment, but it lures us into illogical and absurd conclusions:

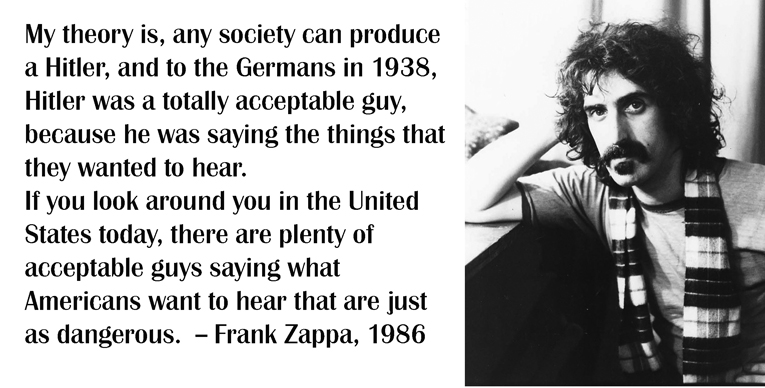

This returns to my oft-quoted remark that Frank Zappa made when I asked him about John Lennon’s wish that Hitler had been treated better as a small child, which was that even if Hitler had never existed, the German people would have found someone else to fill the role because that was where they were headed then.

Zappa, Tolstoy, whoever. If Tolstoy had been a more conventional thinker, we wouldn’t still read his works.

Wisdom considers the flow and doesn’t get hung up on individual moments.

And when Wisdom explores history, it uses what it finds to draw conclusions about the present and the future.

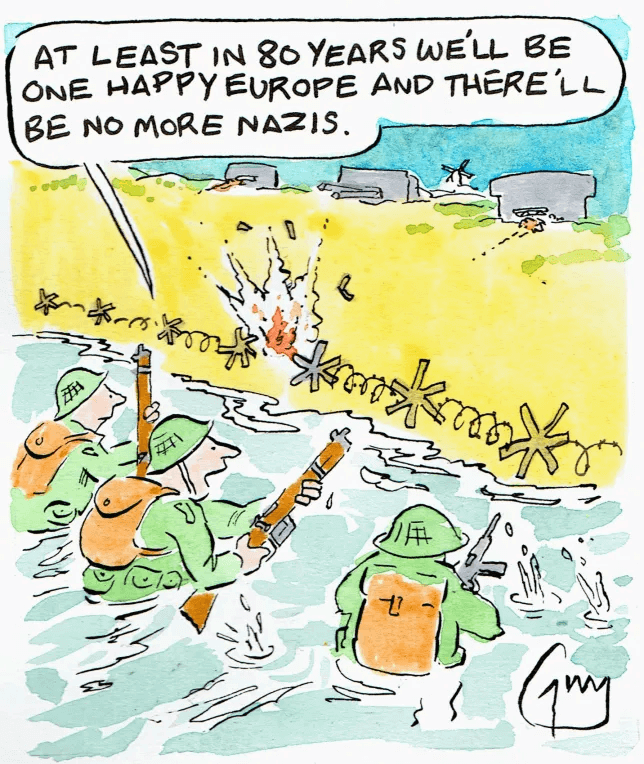

Guy Venables demonstrates how you can do that and retain a sense of humor as long as you add a very strong streak of dark irony.

With perhaps an even stronger acceptance of futility.

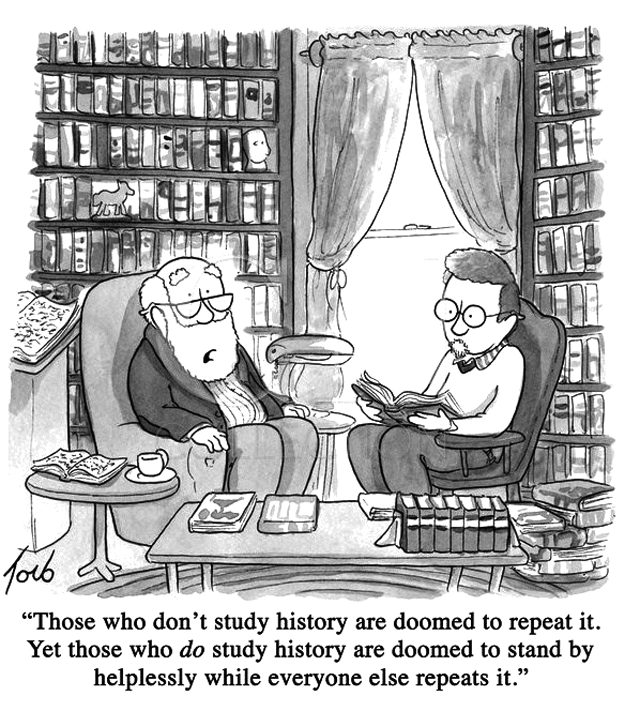

If we’re going to requote Zappa once again, why not drag out Tom Toro for yet another round?

Comments 6

Comments are closed.