Cartoonist Chronicles

Skip to commentsRecent (and not-so-recent) articles on comic and cartoon history.

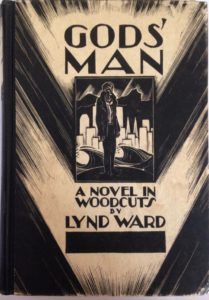

God’s Man, A Novel in Woodcuts by Lynn Ward

This is “Gods’ Man,” a 1929 black-and-white wordless novel that tells a Faustian tale of ambition, love, greed and death. It’s by the illustrator and woodcut artist Lynd Ward. It is widely regarded as the first American book of the form and the urtext of the graphic novel. The story is told through 139 uncaptioned woodblock prints, rendered in a dark, foreboding style that mixes Art Deco beauty with the stern lines of German expressionism. It can leave you breathless with its craftsmanship, vision and narrative detail.

But “Gods’ Man” and Ward’s five subsequent wordless novels were not regarded as a bold new stroke for literature in their day. They were just Depression-era quirks.

Mark Dimunation, chief of the Rare Book and Special Collections Division, wrote about their copy of “Gods’ Man” in an internal memo recently. This is an expanded version of that piece.

An essay from the Library of Congress

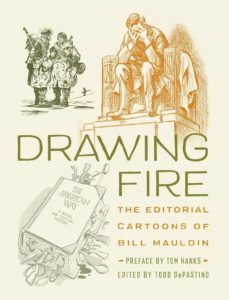

Bill Mauldin – Citizen Soldier

“As a soldier, Mauldin avoided politics. Willie and Joe never trumpeted the Four Freedoms or called for overturning Army hierarchy, even while they griped about officers and Mps. As a civilian, by contrast, Mauldin embraced politics and a number of liberal causes, most notably civil rights and the plight of displaced persons.”

This year would be Mauldin’s 100th birthday. To commemorate his life and work during and after the war, The Pritzker Military Museum & Library in Chicago has published Drawing Fire: The Editorial Cartoons of Bill Mauldin, edited by Todd DePastino.

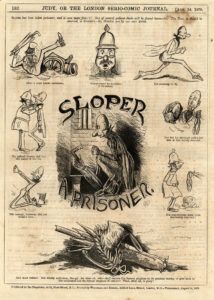

Marie Duval, Pioneering 19th Century Cartoonist

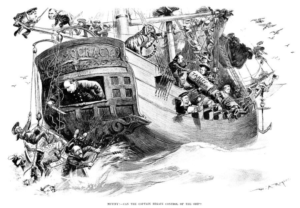

When Judy magazine, a twopenny serio-comic, debuted a red-nosed, lanky schemer named Ally Sloper who represented the poor working class of 19th-century England, it was one of the first recurring characters in comic history.

But credit for that character has long gone to the wrong person. Two people were responsible for Ally Sloper—and one of the creators has only recently been rediscovered by academics and comic fans.

When Ally Sloper grew into a comic celebrity in the 1860s and late 1870s, Duval had become the sole artist behind the mischievous character’s world. She is among the earliest female comic artists, and has even been dubbed “Britain’s only 19th-century female caricaturist,” by art historian David Kunzle. In contrast to the refined artistry of both male and female cartoonists of the time, Duval’s drawing style was rugged and full of slapstick humor.

Lauren Young, at Atlas Obscura, profiles the earliest(?) woman cartoonist.

Ana Olendraru, for Blue Stocking, does the same about the comic illustrator.

The Once and Still Great Ramona Fradon

The [Top 100 Comic Artists] list, we’re told is determined by four factors: technique, storytelling, accomplishments and longevity.

Fradon’s career hits all four categories, in fact shames them all, especially longevity. From her DC work in the ’60s to Brenda Starr to her current busy career with commissions. And she drew in an unmistakable style all her own.

Wonder Woman and Metamorpho © DC Comics

Fradon was and is an amazing, no-nonsense woman who just gets on with her work, and rolls her eyes at the discrimination she faced. She silenced all doubts with her pencil, over and over.

Heidi MacDonald, at Comics Beat, appreciates the underappreciated Ramona Fradon.

It’s Art, But What Kind Of Art

[I]n Bart Beaty’s book Comics Versus Art, he argues comics to be considered alongside a High Art form. Throughout his book, he highlights a problem inherent with this approach to viewing comics, in that by trying to define comics, more often than not, it removes comics from the high art discussion. It creates a contradiction.

There is an unspoken acceptance that some works of art will attain recognition and receive the capital ‘A’ while others will become a part of the general discourse, a way to help set the bar for excellence over the bland. The same is true of Comics, whatever definition of the form you decide on. Some comics will be printed, read, and discarded as nothing more than flights of entertaining fancy, while others will emerge out of the quagmire to be held aloft as fine examples of the medium.

Darryll Robson ruminates on Comic Art for Monkeys Fighting Robots.

The Art of Hank Ketcham

As the years passed I always knew about the strip, due to it’s popularity, but never looked at it closely until one day a friend was in New York on a business trip. The two of us went to Midtown Comics and he said “Take a look at this”. I replied “Dennis the Menace. Are you serious?”. He then explained that Ketcham’s work is well regarded by cartoonists.

Dennis the Menace © North America Syndicate/King Features Syndicate

I quickly walked over to the comic strip aisle and picked up one of the collections published by Fantagraphics. As I flipped through the book I was impressed at how well-thought-out the compositions in those strips are and could tell that a lot work went into each one; Ketcham never dashed off any of his drawings.

Wait. What?

I can understand a W. A. Rogers 1894 cartoon print, but a W. A. Rogers 1894 cartoon beach towel?

Comments 2

Comments are closed.