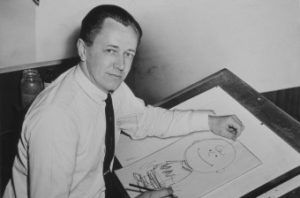

Peanuts: The Defining Comic Strip of Our Time

Skip to commentsFeature article by Matt Blitz at Today I Found Out on Peanuts becoming the popular comic strip it is.

[W]hen the comic strip first appeared in the 1950s, [Snoopy] and his Peanut friends were considered, to quote Time Magazine’s David Michaels, “the fault-line of a cultural earthquake” due to the way the comic depicted life, real characters, and sadness. Garry Trudeau, the creator of Doonesbury, went so far as to call Peanuts “the first Beat strip… everything about it was different…. [it] vibrated with ’50s alienation.”

That theme runs throughout the essay:

Unsurprisingly for a young man who just lost his mother and was soon to experience the horrors of WWII, his drawings from that era were ones of depression and isolation. [Schulz] would later state of his time in the army, “The army taught me all I needed to know about loneliness.”

and

At a time when comic strips were dominated by action-adventure, slapstick, marriage humor, and melodrama, Peanuts was different. The comic expressed sadness, anger, depression, isolation, insecurity, and inferiority.

[A]s for Charlie Brown, said Schulz, “I worry about almost all there is in life to worry about. And because I worry, Charlie Brown has to worry.” Or as Charlie Brown once so succinctly stated, “My anxieties have anxieties.”

But don’t let all that dissuade from reading the article. It is a celebratory recounting of a very successful comic strip and the genius cartoonist that created it.

In the end, Peanuts went on to branch out into TV specials, movies, and best-selling books. According to Forbes, for a time Schulz was one of the highest-paid entertainers in America, during his heyday estimated to have been earning in the realm of $30-$40 million per year, while Peanuts appeared in over two thousands newspapers and was translated into over twenty languages in over 75 countries. On top of that, gross revenues from all sources of revenue related to Peanuts combined saw it bringing in in excess of a whopping $1 billion annually at its peak.

But success wasn’t just monetary, it was a creative success also:

As the creator of Calvin & Hobbes, Bill Waterson, once noted, Schulz somehow turned this oppressive space restriction to his advantage, and developed a brilliant graphic shorthand and stylistic economy, innovations unrecognizable now that all comics are tiny and Schulz’s solutions have been universally imitated.

Matt discusses the introduction of some of the cast members:

For example, in 1966, Schulz introduced Peppermint Patty- a tomboy who wears shorts, open-toed shoes, calls everyone by a nickname, and lives with only her dad.

Peppermint Patty was quickly the strip’s most complex, fully-realized character, who dealt with the political issues of the day without hitting the reader over the head. Yet, she still possessed a similar inferiority complex as almost every other character in the strip- always believing she looked funny and wasn’t quite good enough.

Moving on to 1968, a few months after the assassination of Martin Luther King, Schulz introduced Franklin, Peanuts‘ first black character, who attended the same classes as the white students, became friends with them, and whose father fought in the Vietnam War.

The only error that stood out to me was in the description of the first strip:

Even the first comic strip was slightly off-kilter. It depicts two kids sitting on a curb as a joyous Charlie Brown skips past. “Well! Here comes good ol’ Charlie Brown,” says the sitting child (who would become Linus), “Good ol’ Charlie Brown, yes sir.” The final panel reveals the child’s real feelings with Brown now out of view, “How I hate him!”

I believe, but couldn’t swear to it, that is Shermy, not Linus.

But the article as a whole is an enjoyable and informative read.

Comments 1

Comments are closed.