Comic Strip History Lessons #358 – 365

Skip to commentsThere’s a Man Who Leads a Life of Danger

Secret Agent X-9/Secret Agent Corrigan ran as a daily-only comic strip from 1934 to 1996. Mark Carlson-Ghost looks at the star and co-stars of the strip, and at the creators assigned to the G-man.

Secret Agent X-9 is well known by comic strip fans, but is largely forgotten by the public. But even fans of the comic strip only know the character by its two “golden” periods: the first penned by the author of The Maltese Falcon and drawn by the creator of Flash Gordon. Thirty years later, in 1967, Secret Agent X-9 got a makeover by Archie Goodwin and artist extraordinaire Al Williamson. The two eras are extensively and beautifully preserved in reprint collections. The years between, 1935 to 1966 and post 1980 are barely mentioned and less often seen.

Clicking on tags at the bottom of the article will lead you to like articles on Mary Worth, Judge Parker, Winnie Winkle, Don Winslow, and more.

Que Pasa, New York? Que Pasa, New York?

Stan Mack’s Real Life Funnies ran 1974 to 1995 in the Village Voice.

“Real Life Funnies” remains as an invaluable time capsule of two decades when New York City was still a wild, weird, creative place filled with people who, at the very least, had something interesting to say.

In 2013 Jeremiah Moss sat down with Stan Mack and discussed the strip.

This Little Light of Mine

During the last quarter of the 19th century there flourished a curious sub-genre of American magazine: the lithographic cartoon weekly. They featured sixteen large pages, defined by a color front cover, centerspread, and back cover, nearly all of which was political and satirical in content. The most famous of the cartoon weeklies were published in New York. Puck was the first of the genre. Its most prominent imitators were Judge and Truth.

Richard Samuel West delves into the background of Chicago’s Light lithographic cartoon weekly of 1889 – 1891, where art by talent such as T. E. Powers, Hy Mayer, W. W. Denslow, Peter Newell, Clarence Rigby, and more appeared.

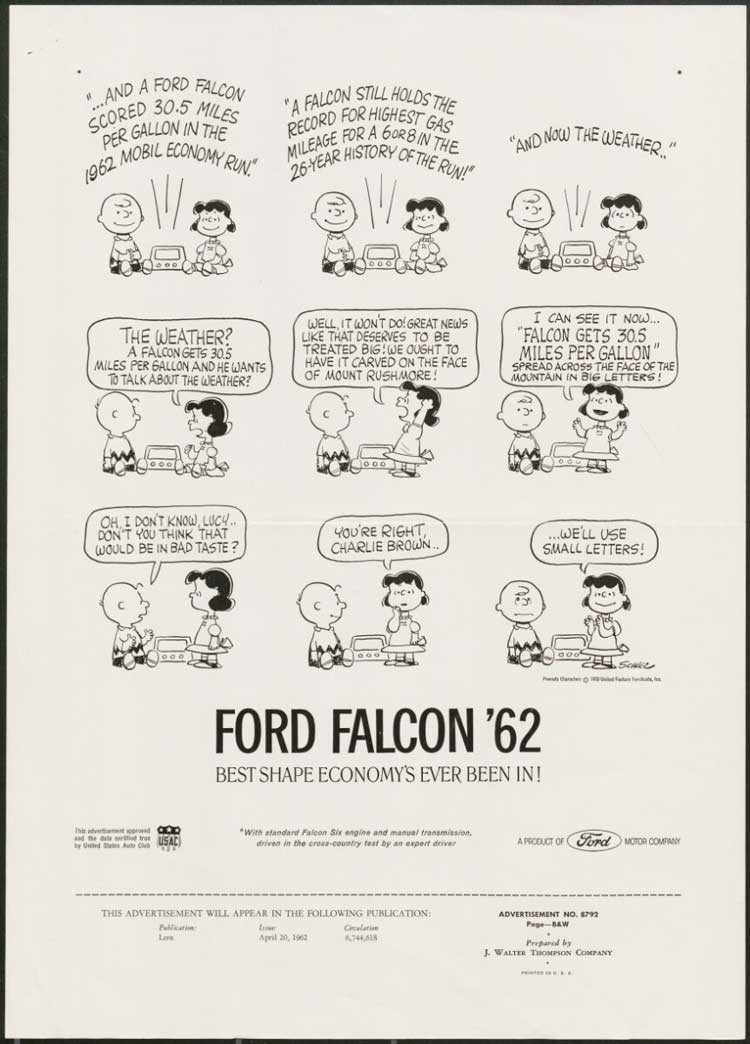

Baby You Can Drive My Car

In the late 50s and 60s, Charles Schulz was offered a contract by Ford Motor Company. The ads for the new compact Ford Falcon aired on TV from 1960 to 1964, with print ads appearing as well.

I’m Gonna Be a Wheel Someday, I’m Gonna Be Somebody

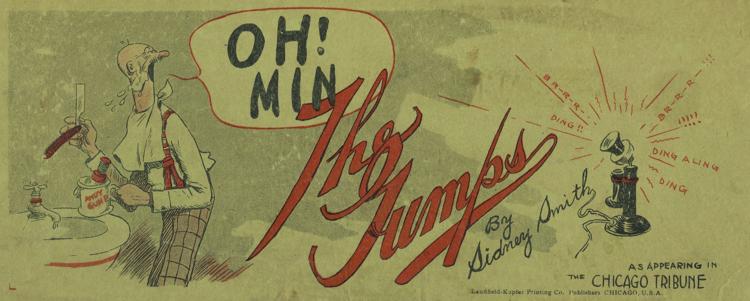

In the spring of 1922, [Sidney] Smith signed a $1 million contract — $100,000 for 10 years guaranteed — with the Tribune. That was a heck of a lot of money back then, and it’d be a lot more today. Adjusted for inflation, $1 million in 1922 would be the equivalent of nearly $15 million today! At the time, the highest paid comic strip artist was Bud Fisher of “Mutt and Jeff” fame, who was paid $50,000 a year. The Tribune also gave Smith a Rolls-Royce, and as if that wasn’t enough, he lobbied for, and eventually received, an oriental rug for his office.

Bill Kemp, for The Pantagraph, looks at a local cartoonist that made good.

You Don’t Know My Name

In the fall of 1961, as [daughter] Cheryl recalls, “he got a ‘Dear John’ letter from NEA saying that Art Sansom was taking over Vic Flint. They didn’t call him; they just sent him a letter When that happened, my father was quite devastated. I think I took it worse than he did. I swore I’d never read another comic, and I haven’t since 1961. I was that upset.”

Dean Miller’s last published comic strip ran on January 21, 1962.

Cartoonist Dean Miller, the comic strip Vic Flint, and the Newspaper Enterprise Association; Frank Young, at The Comics Journal, looks at all three.

Celluloid Heroes Never Really Die

Ron Harris and Alfredo Castelli discuss comic sections that never were.

Am I Just a Face in The Crowd?

Rick Marschall’s Column highlights Dick Moores.

Sidebar

Aaron Sharp introduces his son to Calvin and Hobbes.

Comments

Comments are closed.